Загрузить PDF

Загрузить PDF

Вес — сила, с которой тело действует на опору (или другой вид крепления), возникающая в поле силы тяжести. Масса связана с энергией и импульсом тела и эквивалентна энергии его покоя. Масса не зависит от силы тяжести (точнее от ускорения свободного падения). Поэтому тело, на Земле имеющее массу 20 кг, на Луне будет иметь массу 20 кг, но совсем другой вес (потому что ускорение свободного падения на Луне в 6 раз меньше, чем на Земле).

-

1

Для вычисления веса используйте формулу

. Вес — это сила, с которой тело действует на опору, и его можно рассчитать, зная массу тела. В физике используется формула

.[1]

-

2

Определите массу тела. Так как ускорение свободного падения — это стандартная величина, то необходимо знать массу тела, чтобы найти его вес. Масса должна быть выражена в килограммах.

-

3

Узнайте величину ускорения свободного падения. На Земле, как уже было сказано выше, g = 9,8 м/с2. В других местах Вселенной эта величина меняется.[3]

- Ускорение свободного падения на поверхности Луны приблизительно равно 1,622 м/с2 (примерно в 6 раз меньше, чем на поверхности Земли). Поэтому ваш вес на Луне будет в 6 раз меньше вашего земного веса.[4]

- Ускорение свободного падения на Солнце приблизительно равно 274,0 м/с2 (примерно в 28 раз больше, чем на Земле). Поэтому ваш вес на Солнце будет в 28 раз больше вашего земного веса (если, конечно, вы выживете на Солнце, что еще не факт!).[5]

- Ускорение свободного падения на поверхности Луны приблизительно равно 1,622 м/с2 (примерно в 6 раз меньше, чем на поверхности Земли). Поэтому ваш вес на Луне будет в 6 раз меньше вашего земного веса.[4]

-

4

Подставьте значения в формулу

. Теперь, когда вы знаете массу

и ускорение свободного падения

, подставьте их значения в формулу

. Так вы найдете вес тела (измеряется в ньютонах, Н).

Реклама

-

1

Задача № 1. Найдите вес тела массой 100 кг на поверхности Земли.

-

2

Задача № 2. Найдите вес тела массой 40 кг на поверхности Луны.

-

3

Задача № 3. Найдите массу тела, которое на поверхности Земли весит 549 Н.

Реклама

-

1

Не путайте массу и вес. Самая распространенная ошибка — перепутать вес и массу (что немудрено, ведь в повседневной жизни мы обычно называем массу весом). Но в физике все не так. Запомните, масса — это постоянное свойство объекта, то, сколько в нем вещества (килограммов), где бы он ни находился. Вес — это сила, с которой объект всеми своими килограммами давит на поверхность, и эта сила на разных небесных телах будет различной.

- Масса измеряется в килограммах или граммах. Запомните, что в этих словах, как и в слове «масса», есть буква «м».

-

2

Используйте правильные единицы измерения. В задачах по физике вес или силу измеряют в ньютонах (Н), ускорение свободного падения — в метрах на секунду в квадрате (м/с2), а массу — в килограммах (кг). Если для какой-либо из этих величин вы возьмете не ту единицу измерения, воспользоваться формулой будет нельзя. Если масса в условиях задачи указана в граммах или тоннах, не забудьте перевести ее в килограммы.

Реклама

Приложение: вес, выраженный в кгс

- Ньютон — это единица измерения силы в международной системе единиц СИ. Нередко сила выражается в килограмм-силах, или кгс (в системе единиц МКГСС). Эта единица очень удобна для сравнения весов на Земле и в космосе.

- 1 кгс = 9,8166 Н.

- Разделите вес, выраженный в ньютонах, на 9,80665.

- Вес космонавта, который «весит» 101 кг (то есть его масса равна 101 кг), составляет 101,3 кгс на Северном полюсе и 16,5 кгс на Луне.

- Международная система единиц СИ — система единиц физических величин, которая является наиболее широко используемой системой единиц в мире.

Советы

- Самая трудная задача — уяснить разницу между весом и массой, так как в повседневной жизни слова «вес» и «масса» используются как синонимы. Вес — это сила, измеряемая в ньютонах или килограмм-силах, а не в килограммах. Если вы обсуждаете ваш «вес» с врачом, то вы обсуждаете вашу массу.

- Ускорение свободного падения также может быть выражено в Н/кг. 1 Н/кг = 1 м/с2.

- Плечевые весы измеряют массу (в кг), в то время как весы, работа которых основана на сжатии или расширении пружины, измеряют вес (в кгс).

- Вес космонавта, который «весит» 101 кг (то есть его масса равна 101 кг), составляет 101,3 кгс на Северном полюсе и 16,5 кгс на Луне. На нейтронной звезде он будет весить еще больше, но он, вероятно, этого не заметит.

- Единица измерения «Ньютон» применяется намного чаще (чем удобная «кгс»), так как можно найти множество других величин, если сила измеряется в ньютонах.

Реклама

Предупреждения

- Выражение «атомный вес» не имеет ничего общего с весом атома, это масса. В современной науке оно заменено на выражение «атомная масса».

Реклама

Об этой статье

Эту страницу просматривали 113 683 раза.

Была ли эта статья полезной?

Из-за притяжения Земли все тела имеют вес.

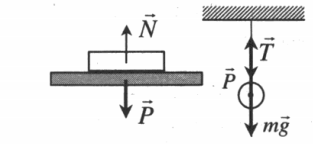

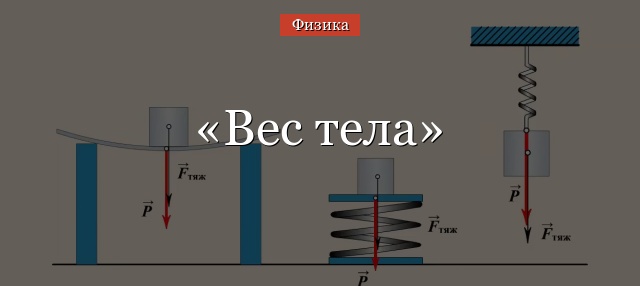

Сила, с которой тело давит на опору или растягивает подвес, называют весом.

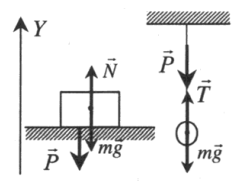

Рис. (1). Тело на опоре, тело на подвесе

Вес тела обозначают (P) и измеряют в ньютонах ((H)).

Вес неподвижного тела равен

P=mg

.

Формула определения веса неподвижного тела точно такая же, как и формула силы тяжести (см. предыдущую тему «Сила. Сила тяжести»). Однако вес тела и сила тяжести — не одно и то же.

Рис. (2). Сила тяжести и вес тела

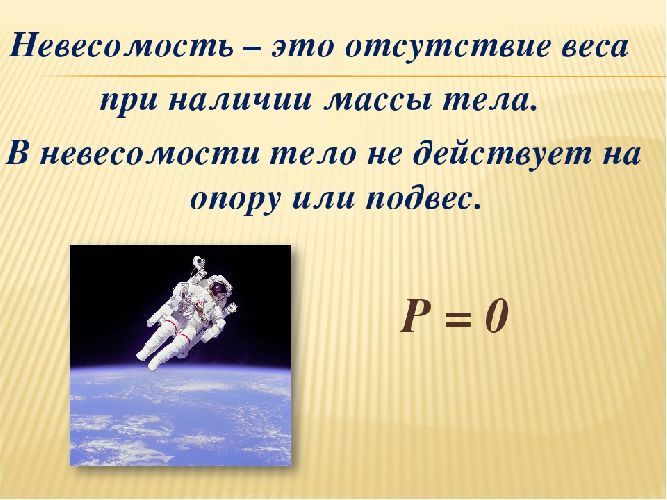

Например, сила тяжести свободно падающего трёхкилограммового кирпича приблизительно составляет (30) (H), ((F = mg)), а его вес (P) в момент падения равен (0) (H) (так как кирпич находится в состоянии невесомости).

Если помещённое на опору или подвешенное тело неподвижно по отношению к Земле или находится в равномерном движении вверх или вниз, тогда вес тела не меняется.

Вес меняется, когда тело перемещается вверх или вниз с ускорением.

Во время поездки в лифте, если мы двигаемся с ускорением вверх, наш вес увеличивается, хотя сила тяжести остаётся неизменной.

Состояние невесомости — это состояние, когда тело не давит на опору и не растягивает подвес. Такое происходит, когда тело свободно падает под воздействием только силы гравитации.

Почему в космическом корабле есть состояние невесомости?

Потому что космический корабль, обращаясь вокруг Земли, находится в свободном падении (он всё время как бы падает на Землю, но пролетает мимо). Это происходит, когда космический корабль достигает 1-й космической скорости — 7,9 км/с.

Если скорость космического корабля была бы меньше, он упал бы на Землю, а если корабль достиг бы 2-й космической скорости — 11,2 км/с, он стал бы искусственным спутником Солнца.

Если скорость космического корабля достигнет 3-й космической скорости — 16,7 км/с, тогда корабль направится из Солнечной системы к другим звёздам.

К сожалению, до ближайшей звёздной системы Альфа Центавра нужно лететь (18000) лет, так как она находится на расстоянии (4) световых лет.

Интересно, что для того, чтобы достичь Луны, ракета должна развить скорость, равную (0,992) от второй космической скорости.

Источники:

Рис. 1. Тело на опоре, тело на подвесе. © ЯКласс.

Рис. 2. Сила тяжести и вес тела. © ЯКласс.

This page is about the physical concept. In law, commerce, and in colloquial usage weight may also refer to mass. For other uses see Weight (disambiguation).

| Weight | |

|---|---|

A spring scale measures the weight of an object. |

|

|

Common symbols |

|

| SI unit | newton (N) |

|

Other units |

pound-force (lbf) |

| In SI base units | kg⋅m⋅s−2 |

| Extensive? | Yes |

| Intensive? | No |

| Conserved? | No |

|

Derivations from |

|

| Dimension |  |

In science and engineering, the weight of an object is the force acting on the object due to acceleration or gravity.[1][2][3]

Some standard textbooks[4] define weight as a vector quantity, the gravitational force acting on the object. Others[5][6] define weight as a scalar quantity, the magnitude of the gravitational force. Yet others[7] define it as the magnitude of the reaction force exerted on a body by mechanisms that counteract the effects of gravity: the weight is the quantity that is measured by, for example, a spring scale. Thus, in a state of free fall, the weight would be zero. In this sense of weight, terrestrial objects can be weightless: ignoring air resistance, the famous apple falling from the tree, on its way to meet the ground near Isaac Newton, would be weightless.

The unit of measurement for weight is that of force, which in the International System of Units (SI) is the newton. For example, an object with a mass of one kilogram has a weight of about 9.8 newtons on the surface of the Earth, and about one-sixth as much on the Moon. Although weight and mass are scientifically distinct quantities, the terms are often confused with each other in everyday use (e.g. comparing and converting force weight in pounds to mass in kilograms and vice versa).[8]

Further complications in elucidating the various concepts of weight have to do with the theory of relativity according to which gravity is modeled as a consequence of the curvature of spacetime. In the teaching community, a considerable debate has existed for over half a century on how to define weight for their students. The current situation is that a multiple set of concepts co-exist and find use in their various contexts.[2]

History[edit]

Weighing grain, from the Babur-namah[9]

Discussion of the concepts of heaviness (weight) and lightness (levity) date back to the ancient Greek philosophers. These were typically viewed as inherent properties of objects. Plato described weight as the natural tendency of objects to seek their kin. To Aristotle, weight and levity represented the tendency to restore the natural order of the basic elements: air, earth, fire and water. He ascribed absolute weight to earth and absolute levity to fire. Archimedes saw weight as a quality opposed to buoyancy, with the conflict between the two determining if an object sinks or floats. The first operational definition of weight was given by Euclid, who defined weight as: «the heaviness or lightness of one thing, compared to another, as measured by a balance.»[2] Operational balances (rather than definitions) had, however, been around much longer.[10]

According to Aristotle, weight was the direct cause of the falling motion of an object, the speed of the falling object was supposed to be directly proportionate to the weight of the object. As medieval scholars discovered that in practice the speed of a falling object increased with time, this prompted a change to the concept of weight to maintain this cause-effect relationship. Weight was split into a «still weight» or pondus, which remained constant, and the actual gravity or gravitas, which changed as the object fell. The concept of gravitas was eventually replaced by Jean Buridan’s impetus, a precursor to momentum.[2]

The rise of the Copernican view of the world led to the resurgence of the Platonic idea that like objects attract but in the context of heavenly bodies. In the 17th century, Galileo made significant advances in the concept of weight. He proposed a way to measure the difference between the weight of a moving object and an object at rest. Ultimately, he concluded weight was proportionate to the amount of matter of an object, not the speed of motion as supposed by the Aristotelean view of physics.[2]

Newton[edit]

The introduction of Newton’s laws of motion and the development of Newton’s law of universal gravitation led to considerable further development of the concept of weight. Weight became fundamentally separate from mass. Mass was identified as a fundamental property of objects connected to their inertia, while weight became identified with the force of gravity on an object and therefore dependent on the context of the object. In particular, Newton considered weight to be relative to another object causing the gravitational pull, e.g. the weight of the Earth towards the Sun.[2]

Newton considered time and space to be absolute. This allowed him to consider concepts as true position and true velocity.[clarification needed] Newton also recognized that weight as measured by the action of weighing was affected by environmental factors such as buoyancy. He considered this a false weight induced by imperfect measurement conditions, for which he introduced the term apparent weight as compared to the true weight defined by gravity.[2]

Although Newtonian physics made a clear distinction between weight and mass, the term weight continued to be commonly used when people meant mass. This led the 3rd General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM) of 1901 to officially declare «The word weight denotes a quantity of the same nature as a force: the weight of a body is the product of its mass and the acceleration due to gravity», thus distinguishing it from mass for official usage.

Relativity[edit]

In the 20th century, the Newtonian concepts of absolute time and space were challenged by relativity. Einstein’s equivalence principle put all observers, moving or accelerating, on the same footing. This led to an ambiguity as to what exactly is meant by the force of gravity and weight. A scale in an accelerating elevator cannot be distinguished from a scale in a gravitational field. Gravitational force and weight thereby became essentially frame-dependent quantities. This prompted the abandonment of the concept as superfluous in the fundamental sciences such as physics and chemistry. Nonetheless, the concept remained important in the teaching of physics. The ambiguities introduced by relativity led, starting in the 1960s, to considerable debate in the teaching community as how to define weight for their students, choosing between a nominal definition of weight as the force due to gravity or an operational definition defined by the act of weighing.[2]

Definitions[edit]

This top-fuel dragster can accelerate from zero to 160 kilometres per hour (99 mph) in 0.86 seconds. This is a horizontal acceleration of 5.3 g. Combined with the vertical g-force in the stationary case the Pythagorean theorem yields a g-force of 5.4 g. It is this g-force that causes the driver’s weight if one uses the operational definition. If one uses the gravitational definition, the driver’s weight is unchanged by the motion of the car.

Several definitions exist for weight, not all of which are equivalent.[3][11][12][13]

Gravitational definition[edit]

The most common definition of weight found in introductory physics textbooks defines weight as the force exerted on a body by gravity.[1][13] This is often expressed in the formula W = mg, where W is the weight, m the mass of the object, and g gravitational acceleration.

In 1901, the 3rd General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM) established this as their official definition of weight:

The word weight denotes a quantity of the same nature[Note 1] as a force: the weight of a body is the product of its mass and the acceleration due to gravity.

— Resolution 2 of the 3rd General Conference on Weights and Measures[15][16]

This resolution defines weight as a vector, since force is a vector quantity. However, some textbooks also take weight to be a scalar by defining:

The weight W of a body is equal to the magnitude Fg of the gravitational force on the body.[17]

The gravitational acceleration varies from place to place. Sometimes, it is simply taken to have a standard value of 9.80665 m/s2, which gives the standard weight.[15]

The force whose magnitude is equal to mg newtons is also known as the m kilogram weight (which term is abbreviated to kg-wt)[18]

Left: A spring scale measures weight, by seeing how much the object pushes on a spring (inside the device). On the Moon, an object would give a lower reading. Right: A balance scale indirectly measures mass, by comparing an object to references. On the Moon, an object would give the same reading, because the object and references would both become lighter.

Operational definition[edit]

In the operational definition, the weight of an object is the force measured by the operation of weighing it, which is the force it exerts on its support.[11] Since W is the downward force on the body by the centre of earth and there is no acceleration in the body, there exists an opposite and equal force by the support on the body. Also it is equal to the force exerted by the body on its support because action and reaction have same numerical value and opposite direction. This can make a considerable difference, depending on the details; for example, an object in free fall exerts little if any force on its support, a situation that is commonly referred to as weightlessness. However, being in free fall does not affect the weight according to the gravitational definition. Therefore, the operational definition is sometimes refined by requiring that the object be at rest.[citation needed] However, this raises the issue of defining «at rest» (usually being at rest with respect to the Earth is implied by using standard gravity).[citation needed] In the operational definition, the weight of an object at rest on the surface of the Earth is lessened by the effect of the centrifugal force from the Earth’s rotation.

The operational definition, as usually given, does not explicitly exclude the effects of buoyancy, which reduces the measured weight of an object when it is immersed in a fluid such as air or water. As a result, a floating balloon or an object floating in water might be said to have zero weight.

ISO definition[edit]

In the ISO International standard ISO 80000-4:2006,[19] describing the basic physical quantities and units in mechanics as a part of the International standard ISO/IEC 80000, the definition of weight is given as:

Definition

,

- where m is mass and g is local acceleration of free fall.

Remarks

- When the reference frame is Earth, this quantity comprises not only the local gravitational force, but also the local centrifugal force due to the rotation of the Earth, a force which varies with latitude.

- The effect of atmospheric buoyancy is excluded in the weight.

- In common parlance, the name «weight» continues to be used where «mass» is meant, but this practice is deprecated.

— ISO 80000-4 (2006)

The definition is dependent on the chosen frame of reference. When the chosen frame is co-moving with the object in question then this definition precisely agrees with the operational definition.[12] If the specified frame is the surface of the Earth, the weight according to the ISO and gravitational definitions differ only by the centrifugal effects due to the rotation of the Earth.

Apparent weight[edit]

In many real world situations the act of weighing may produce a result that differs from the ideal value provided by the definition used. This is usually referred to as the apparent weight of the object. A common example of this is the effect of buoyancy, when an object is immersed in a fluid the displacement of the fluid will cause an upward force on the object, making it appear lighter when weighed on a scale.[20] The apparent weight may be similarly affected by levitation and mechanical suspension. When the gravitational definition of weight is used, the operational weight measured by an accelerating scale is often also referred to as the apparent weight.[21]

Mass[edit]

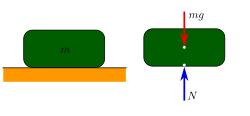

An object with mass m resting on a surface and the corresponding free body diagram of just the object showing the forces acting on it. The magnitude of force that the table is pushing upward on the object (the N vector) is equal to the downward force of the object’s weight (shown here as mg, as weight is equal to the object’s mass multiplied with the acceleration due to gravity): because these forces are equal, the object is in a state of equilibrium (all the forces and moments acting on it sum to zero).

In modern scientific usage, weight and mass are fundamentally different quantities: mass is an intrinsic property of matter, whereas weight is a force that results from the action of gravity on matter: it measures how strongly the force of gravity pulls on that matter. However, in most practical everyday situations the word «weight» is used when, strictly, «mass» is meant.[8][22] For example, most people would say that an object «weighs one kilogram», even though the kilogram is a unit of mass.

The distinction between mass and weight is unimportant for many practical purposes because the strength of gravity does not vary too much on the surface of the Earth. In a uniform gravitational field, the gravitational force exerted on an object (its weight) is directly proportional to its mass. For example, object A weighs 10 times as much as object B, so therefore the mass of object A is 10 times greater than that of object B. This means that an object’s mass can be measured indirectly by its weight, and so, for everyday purposes, weighing (using a weighing scale) is an entirely acceptable way of measuring mass. Similarly, a balance measures mass indirectly by comparing the weight of the measured item to that of an object(s) of known mass. Since the measured item and the comparison mass are in virtually the same location, so experiencing the same gravitational field, the effect of varying gravity does not affect the comparison or the resulting measurement.

The Earth’s gravitational field is not uniform but can vary by as much as 0.5%[23] at different locations on Earth (see Earth’s gravity). These variations alter the relationship between weight and mass, and must be taken into account in high-precision weight measurements that are intended to indirectly measure mass. Spring scales, which measure local weight, must be calibrated at the location at which the objects will be used to show this standard weight, to be legal for commerce.[citation needed]

This table shows the variation of acceleration due to gravity (and hence the variation of weight) at various locations on the Earth’s surface.[24]

| Location | Latitude | m/s2 | Absolute difference from equator | Percentage difference from equator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equator | 0° | 9.7803 | 0.0000 | 0% |

| Sydney | 33°52′ S | 9.7968 | 0.0165 | 0.17% |

| Aberdeen | 57°9′ N | 9.8168 | 0.0365 | 0.37% |

| North Pole | 90° N | 9.8322 | 0.0519 | 0.53% |

The historical use of «weight» for «mass» also persists in some scientific terminology – for example, the chemical terms «atomic weight», «molecular weight», and «formula weight», can still be found rather than the preferred «atomic mass», etc.

In a different gravitational field, for example, on the surface of the Moon, an object can have a significantly different weight than on Earth. The gravity on the surface of the Moon is only about one-sixth as strong as on the surface of the Earth. A one-kilogram mass is still a one-kilogram mass (as mass is an intrinsic property of the object) but the downward force due to gravity, and therefore its weight, is only one-sixth of what the object would have on Earth. So a man of mass 180 pounds weighs only about 30 pounds-force when visiting the Moon.

SI units[edit]

In most modern scientific work, physical quantities are measured in SI units. The SI unit of weight is the same as that of force: the newton (N) – a derived unit which can also be expressed in SI base units as kg⋅m/s2 (kilograms times metres per second squared).[22]

In commercial and everyday use, the term «weight» is usually used to mean mass, and the verb «to weigh» means «to determine the mass of» or «to have a mass of». Used in this sense, the proper SI unit is the kilogram (kg).[22]

Pound and other non-SI units[edit]

In United States customary units, the pound can be either a unit of force or a unit of mass.[25] Related units used in some distinct, separate subsystems of units include the poundal and the slug. The poundal is defined as the force necessary to accelerate an object of one-pound mass at 1 ft/s2, and is equivalent to about 1/32.2 of a pound-force. The slug is defined as the amount of mass that accelerates at 1 ft/s2 when one pound-force is exerted on it, and is equivalent to about 32.2 pounds (mass).

The kilogram-force is a non-SI unit of force, defined as the force exerted by a one-kilogram mass in standard Earth gravity (equal to 9.80665 newtons exactly). The dyne is the cgs unit of force and is not a part of SI, while weights measured in the cgs unit of mass, the gram, remain a part of SI.

Sensation[edit]

The sensation of weight is caused by the force exerted by fluids in the vestibular system, a three-dimensional set of tubes in the inner ear.[dubious – discuss] It is actually the sensation of g-force, regardless of whether this is due to being stationary in the presence of gravity, or, if the person is in motion, the result of any other forces acting on the body such as in the case of acceleration or deceleration of a lift, or centrifugal forces when turning sharply.

Measuring[edit]

Weight is commonly measured using one of two methods. A spring scale or hydraulic or pneumatic scale measures local weight, the local force of gravity on the object (strictly apparent weight force). Since the local force of gravity can vary by up to 0.5% at different locations, spring scales will measure slightly different weights for the same object (the same mass) at different locations. To standardize weights, scales are always calibrated to read the weight an object would have at a nominal standard gravity of 9.80665 m/s2 (approx. 32.174 ft/s2). However, this calibration is done at the factory. When the scale is moved to another location on Earth, the force of gravity will be different, causing a slight error. So to be highly accurate and legal for commerce, spring scales must be re-calibrated at the location at which they will be used.

A balance on the other hand, compares the weight of an unknown object in one scale pan to the weight of standard masses in the other, using a lever mechanism – a lever-balance. The standard masses are often referred to, non-technically, as «weights». Since any variations in gravity will act equally on the unknown and the known weights, a lever-balance will indicate the same value at any location on Earth. Therefore, balance «weights» are usually calibrated and marked in mass units, so the lever-balance measures mass by comparing the Earth’s attraction on the unknown object and standard masses in the scale pans. In the absence of a gravitational field, away from planetary bodies (e.g. space), a lever-balance would not work, but on the Moon, for example, it would give the same reading as on Earth. Some balances are marked in weight units, but since the weights are calibrated at the factory for standard gravity, the balance will measure standard weight, i.e. what the object would weigh at standard gravity, not the actual local force of gravity on the object.

If the actual force of gravity on the object is needed, this can be calculated by multiplying the mass measured by the balance by the acceleration due to gravity – either standard gravity (for everyday work) or the precise local gravity (for precision work). Tables of the gravitational acceleration at different locations can be found on the web.

Gross weight is a term that is generally found in commerce or trade applications, and refers to the total weight of a product and its packaging. Conversely, net weight refers to the weight of the product alone, discounting the weight of its container or packaging; and tare weight is the weight of the packaging alone.

Relative weights on the Earth and other celestial bodies[edit]

The table below shows comparative gravitational accelerations at the surface of the Sun, the Earth’s moon, each of the planets in the solar system. The “surface” is taken to mean the cloud tops of the gas giants (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune). For the Sun, the surface is taken to mean the photosphere. The values in the table have not been de-rated for the centrifugal effect of planet rotation (and cloud-top wind speeds for the gas giants) and therefore, generally speaking, are similar to the actual gravity that would be experienced near the poles.

| Body | Multiple of Earth gravity |

Surface gravity m/s2 |

|---|---|---|

| Sun | 27.90 | 274.1 |

| Mercury | 0.3770 | 3.703 |

| Venus | 0.9032 | 8.872 |

| Earth | 1 (by definition) | 9.8226[26] |

| Moon | 0.1655 | 1.625 |

| Mars | 0.3895 | 3.728 |

| Jupiter | 2.640 | 25.93 |

| Saturn | 1.139 | 11.19 |

| Uranus | 0.917 | 9.01 |

| Neptune | 1.148 | 11.28 |

See also[edit]

- Human body weight – Person’s mass or weight

- Tare weight

- weight – Unit of weight the English unit

Notes[edit]

- ^ The phrase «quantity of the same nature» is a literal translation of the French phrase grandeur de la même nature. Although this is an authorized translation, VIM 3 of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures recommends translating grandeurs de même nature as quantities of the same kind.[14]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Richard C. Morrison (1999). «Weight and gravity — the need for consistent definitions». The Physics Teacher. 37 (1): 51. Bibcode:1999PhTea..37…51M. doi:10.1119/1.880152.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Igal Galili (2001). «Weight versus gravitational force: historical and educational perspectives». International Journal of Science Education. 23 (10): 1073. Bibcode:2001IJSEd..23.1073G. doi:10.1080/09500690110038585. S2CID 11110675.

- ^ a b Gat, Uri (1988). «The weight of mass and the mess of weight». In Richard Alan Strehlow (ed.). Standardization of Technical Terminology: Principles and Practice – second volume. ASTM International. pp. 45–48. ISBN 978-0-8031-1183-7.

- ^ Knight, Randall D. (2004). Physics for Scientists and Engineers: a Strategic Approach. San Francisco, USA: Addison–Wesley. pp. 100–101. ISBN 0-8053-8960-1.

- ^ Bauer, Wolfgang and Westfall, Gary D. (2011). University Physics with Modern Physics. New York: McGraw Hill. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-07-336794-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Serway, Raymond A. and Jewett, John W. Jr. (2008). Physics for Scientists and Engineers with Modern Physics. USA: Thompson. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-495-11245-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hewitt, Paul G. (2001). Conceptual Physics. USA: Addison–Wesley. pp. 159. ISBN 0-321-05202-1.

- ^ a b The National Standard of Canada, CAN/CSA-Z234.1-89 Canadian Metric Practice Guide, January 1989:

- 5.7.3 Considerable confusion exists in the use of the term «weight». In commercial and everyday use, the term «weight» nearly always means mass. In science and technology «weight» has primarily meant a force due to gravity. In scientific and technical work, the term «weight» should be replaced by the term «mass» or «force», depending on the application.

- 5.7.4 The use of the verb «to weigh» meaning «to determine the mass of», e.g., «I weighed this object and determined its mass to be 5 kg,» is correct.

- ^ Sur Das (1590s). «Weighing Grain». Baburnama.

- ^ http://www.averyweigh-tronix.com/museum Archived 2013-02-28 at the Wayback Machine accessed 29 March 2013.

- ^ a b Allen L. King (1963). «Weight and weightlessness». American Journal of Physics. 30 (5): 387. Bibcode:1962AmJPh..30..387K. doi:10.1119/1.1942032.

- ^ a b A. P. French (1995). «On weightlessness». American Journal of Physics. 63 (2): 105–106. Bibcode:1995AmJPh..63..105F. doi:10.1119/1.17990.

- ^ a b Galili, I.; Lehavi, Y. (2003). «The importance of weightlessness and tides in teaching gravitation» (PDF). American Journal of Physics. 71 (11): 1127–1135. Bibcode:2003AmJPh..71.1127G. doi:10.1119/1.1607336.

- ^ Working Group 2 of the Joint Committee for Guides in Metrology (JCGM/WG 2) (2008). International vocabulary of metrology – Basic and general concepts and associated terms (VIM) – Vocabulaire international de métrologie – Concepts fondamentaux et généraux et termes associés (VIM) (PDF) (JCGM 200:2008) (in English and French) (3rd ed.). BIPM. Note 3 to Section 1.2.

- ^ a b «Resolution of the 3rd meeting of the CGPM (1901)». BIPM.

- ^ David B. Newell; Eite Tiesinga, eds. (2019). The International System of Units (SI) (PDF) (NIST Special publication 330, 2019 ed.). Gaithersburg, MD: NIST. p. 46.

- ^ Halliday, David; Resnick, Robert; Walker, Jearl (2007). Fundamentals of Physics. Vol. 1 (8th ed.). Wiley. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-470-04473-5.

- ^ Chester, W. Mechanics. George Allen & Unwin. London. 1979. ISBN 0-04-510059-4. Section 3.2 at page 83.

- ^ ISO 80000-4:2006, Quantities and units — Part 4: Mechanics

- ^ Bell, F. (1998). Principles of mechanics and biomechanics. Stanley Thornes Ltd. pp. 174–176. ISBN 978-0-7487-3332-3.

- ^ Galili, Igal (1993). «Weight and gravity: teachers’ ambiguity and students’ confusion about the concepts». International Journal of Science Education. 15 (2): 149–162. Bibcode:1993IJSEd..15..149G. doi:10.1080/0950069930150204.

- ^ a b c A. Thompson & B. N. Taylor (March 3, 2010) [July 2, 2009]. «The NIST Guide for the use of the International System of Units, Section 8: Comments on Some Quantities and Their Units». Special Publication 811. NIST. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ^ Hodgeman, Charles, ed. (1961). Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (44th ed.). Cleveland, USA: Chemical Rubber Publishing Co. pp. 3480–3485.

- ^ Clark, John B (1964). Physical and Mathematical Tables. Oliver and Boyd.

- ^ «Common Conversion Factors, Approximate Conversions from U.S. Customary Measures to Metric». Nist. National Institute of Standards and Technology. 13 January 2010. Retrieved 2013-09-03.

- ^ This value excludes the adjustment for centrifugal force due to Earth’s rotation and is therefore greater than the 9.80665 m/s2 value of standard gravity.

Вес тела — сила, с которой тело вследствие притяжения к Земле давит на опору или растягивает подвес.

Вес тела имеет электромагнитную природу (не путать с силой тяжести – она возникает между двумя телами и имеет гравитационную природу!). Обозначается P. Измеряется динамометром. Единица измерения — Н (Ньютон).

Вес имеет направление, противоположное силе реакции опоры или силе натяжения нити. Точкой приложения веса является точка опоры или подвеса: P↑↓N или P↑↓T.

Согласно III закону Ньютона модуль веса тела определяется одной из следующих формул:

P = T; P = N; P = Fупр.

Если тело и опора или подвес неподвижны, то модули силы реакции опоры, силы натяжения подвеса, а также силы упругости равны модулю силы тяжести. Поэтому в неподвижной системе модуль веса неподвижного тела тоже равен модулю силы тяжести:

P0 = Fтяж = mg

Если тело находится в состоянии невесомости, его вес равен нулю: P = 0. Это значит, что это тело не оказывает никакого действия ни на подвес, ни на опору.

Пример №1. Гиря массой 1 пуд стоит на полу. Определить вес гири.

Так как гиря покоится, ее вес будет равен модулю силы тяжести. 1 пуд = 16,38 кг. Следовательно:

P = mg = 16,38∙10 = 163,8 (Н)

Перегрузка

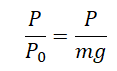

Перегрузка — отношение абсолютной величины линейного ускорения, вызванного негравитационными силами, к стандартному ускорению свободного падения на поверхности.

Перегрузка определяется отношением:

Перегрузка возникает, когда система, в которой находится тело, движется с ускорением.

Вес тела в движущейся равноускоренно системе

Вес тела в движущейся системе может быть больше или меньше веса того же тела в системе, которая находится в состоянии покоя:

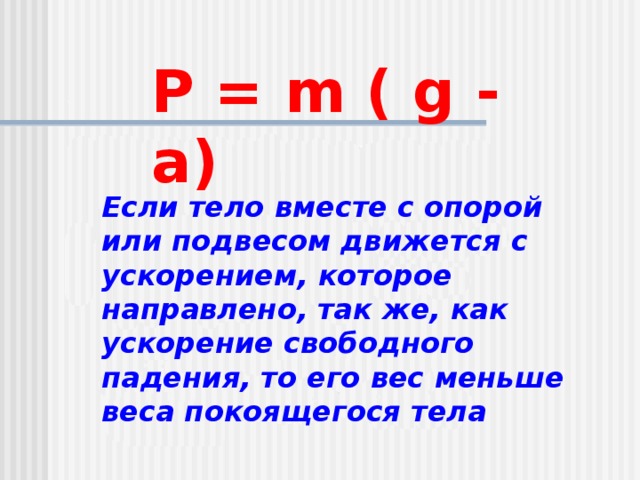

- Если система движется равноускоренно в направлении ускорения свободного падения, вес тела меньше веса тела в неподвижной системе: при a↑↑g — P < P0.

- Если система движется равноускоренно в направлении, противоположном ускорению свободного падения, вес тела больше веса тела в неподвижной системе: при a↑↓g — P > P0.

- Если система движется с равномерной скоростью (ускорение равно нулю) в любом направлении по отношению к ускорению свободного падения, вес тела равен весу тела в неподвижной системе: при a = 0 — P = P0.

Применение законов Ньютона для определения веса тела

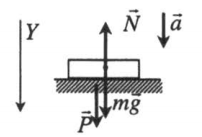

Опора или подвес неподвижны |

|

|

Второй закон Ньютона в векторной форме:

N + mg = ma или T + mg = ma Проекция на ось ОУ: N – mg = 0 или T — mg = 0 |

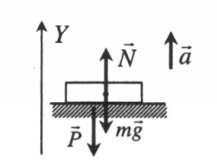

Ускорение опоры направлено вверх |

|

|

Второй закон Ньютона в векторной форме:

N + mg = ma Проекция на ось ОУ: N – mg = ma Вес тела: P = N = ma + mg = m(a + g) |

Ускорение опоры направлено вниз |

|

|

Второй закон Ньютона в векторной форме:

N + mg = ma Проекция на ось ОУ: mg – N = ma Вес тела: P = N = mg – ma = m(g – a) |

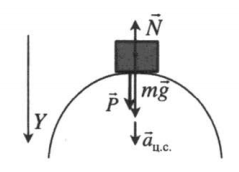

Вершина выпуклого моста |

|

|

Второй закон Ньютона в векторной форме:

N + mg = maц.с. Проекция на ось ОУ: mg – N = m aц.с. Вес тела: P = N = mg – m aц.с. = m(g – aц.с.) |

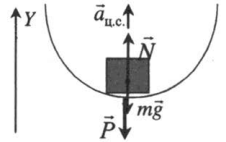

Нижняя точка вогнутого моста |

|

|

Второй закон Ньютона в векторной форме:

N + mg = maц.с. Проекция на ось ОУ: N – mg = maц.с. Вес тела: P = N = maц.с. + mg = m(aц.с. + g) |

Полный оборот на подвесе |

|

|

Второй закон Ньютона в векторной форме:

T + mg = ma Проекция на ось ОУ в точке А: T + mg = maц.с. Вес тела в точке А: P = T = maц.с. – mg = m (aц.с. – g) Проекция на ось ОУ в точке В: T – mg = maц.с. Вес тела в точке В: P = T = maц.с. + mg = m (aц.с. + g) Важно! Центростремительное ускорение всегда направлено к центру окружности. |

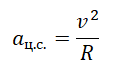

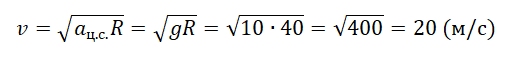

Пример №2. Автомобиль массой 1000 кг едет по выпуклому мосту с радиусом кривизны 40 м. Какую скорость должен иметь автомобиль в верхней точке моста, чтобы пассажиры в этой точке почувствовали невесомость?

Вес тела в верхней точке выпуклого моста равен:

P = m(g – aц.с.)

Чтобы пассажиры почувствовали состояние невесомости, вес тела должен быть равен 0:

m(g – aц.с.) = 0

Масса не может быть нулевой, поэтому:

g – aц.с. = 0

g = aц.с

Значит, пассажиры в верхней точке моста почувствуют невесомость, если центростремительное ускорение будет равно ускорению свободного падения. Центростремительное ускорение определяется формулой:

Отсюда скорость автомобиля в верхней точке моста должна быть равна:

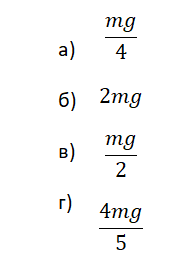

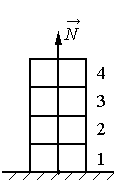

Задание EF18133

Алгоритм решения

1.Вычислить силу, с которой оставшиеся кирпичи давят на опору.

2.Применить третий закон Ньютона.

3.Определить силу, с которой действует горизонтальная опора на первый кирпич.

Решение

Так как кирпичи покоятся, вес каждого равен:

P = mg

Вес двух кирпичей равен:

2P = 2mg

Опора действует на первый кирпич с такой же силой, с какой на него действует два кирпича, оставшихся после того, как два верхних кирпича убрали.

Следовательно:

N = 2P = 2mg

Ответ: б

pазбирался: Алиса Никитина | обсудить разбор

Задание EF17624

Подъёмный кран поднимает груз с постоянным ускорением. На груз со стороны каната действует сила, равная по величине 8⋅103 H. На канат со стороны груза действует сила, которая:

а) 8∙103 Н

б) меньше 8∙103 Н

в) больше 8∙103 Н

г) равна силе тяжести, действующей на груз

Алгоритм решения

1.Сформулировать третий закон Ньютона.

2.Применить закон Ньютона к канату и грузу.

3.На основании закона сделать вывод и определить силу, которая действует на канат со стороны груза.

Решение

Третий закон Ньютона формулируется так:

«Силы, с которыми тела действуют друг на друга, равны по модулям и направлены по одной прямой в противоположные стороны».

Математически он записывается так:

FA = –FB

Если на груз со стороны каната действует некоторая сила, то и груз действует на канат с этой силой, которая называется весом этого груза, или силой натяжения нити. Следовательно, груз действует на канат с силой 8∙103 Н.

Ответ: а

pазбирался: Алиса Никитина | обсудить разбор

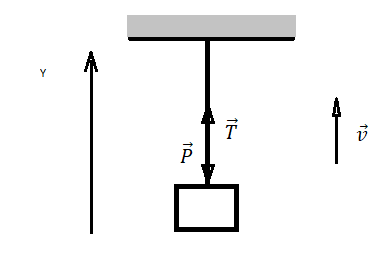

Задание EF22586

Мальчик медленно поднимает гирю, действуя на неё с силой 100 Н. Гиря действует на руку мальчика с силой:

а) больше 100 Н, направленной вниз

б) меньше 100 Н, направленной вверх

в) 100 Н, направленной вниз

г) 100 Н, направленной вверх

Алгоритм решения

1.Записать исходные данные.

2.Сделать чертеж, иллюстрирующий ситуацию.

3.Записать второй закон Ньютона в векторной форме.

4.Записать второй закон Ньютона в виде проекций.

5.Вычислить силу, с которой гиря действует на руку мальчика.

Решение

Запишем исходные данные: мальчик поднимает гирю вверх с силой F = 100 Н.

Сделаем рисунок. В данном случае рука мальчика выступает в роли подвеса. Так как мальчик поднимает гирю медленно, можно считать, что он поднимает ее равномерно (равнодействующая всех сил равна нулю). Выберем систему координат, направление оси которой совпадает с направлением движения руки и гири.

На руку (подвес) действуют только две силы. Поэтому второй закон Ньютона выглядит следующим образом:

P + T = 0

Запишем этот же закон в проекции на ось ОУ:

–P + T = 0

Отсюда:

P = T

Следовательно, на руку мальчика действует вес гири, который по модулю равен силе, с которой мальчик действует на эту гирю.

Внимание! Существует второй способ решения задачи через третий закон Ньютона. Согласно ему, тела действуют друг на друга с силами, равными по модулю, но противоположными по направлению.

Ответ: в

pазбирался: Алиса Никитина | обсудить разбор

Алиса Никитина | Просмотров: 6.6k

Вес тела

4.2

Средняя оценка: 4.2

Всего получено оценок: 101.

Обновлено 16 Июля, 2021

4.2

Средняя оценка: 4.2

Всего получено оценок: 101.

Обновлено 16 Июля, 2021

Понятие «вес тела» очень часто используется в повседневной жизни. Многие продукты и материалы покупаются, исходя из измеренного веса. Как правило, в быту понятие веса отождествляется с понятием массы тела. Однако в физике это не одно и то же. Более того, эти величины не равны. Рассмотрим эту тему подробнее, приведём определение и формулу веса тела.

Вес тела

Чтобы понять физическую природу веса тела, достаточно вспомнить, как происходит взвешивание на пружинных весах. На чашку весов укладывается тело, под действием силы тяжести оно сжимает пружину, и по степени этого сжатия можно судить о том, сколько весит тело.

То есть сила, с которой тело воздействует на опору, называется весом.

Найдём величину этой силы. На тело, имеющее опору, действует сила тяжести $m overrightarrow {mathrm{g}}$ и сила реакции опоры $ overrightarrow {N}$.

По третьему закону Ньютона, тело также действует на опору с равной силой $ overrightarrow {P}= – overrightarrow {N}$ (противоположной по направлению). Эта сила и есть вес тела.

Если опора (и тело вместе с ней) движется вверх с ускорением $ overrightarrow {a}$, то по второму закону Ньютона имеем:

$$overrightarrow {N}+ m overrightarrow {mathrm{g}} = m overrightarrow {a}$$

Учитывая равенство веса и его противоположную направленность относительно реакции опоры, после проецирования на ось координат, направленную вниз, можно записать:

$$P = m (mathrm{g} – a)$$

Это и есть формула веса тела массой $m$, существующего в условиях гравитации (ускорение свободного падения $mathrm{g}$), имеющего опору, которая двигается вверх с ускорением $a$.

Свойства веса тела

Из вышесказанного можно сделать важные выводы.

- Во-первых, как физическая величина, вес является силой. Поэтому единица измерения веса в физике — ньютон.

- Во-вторых, вес — фактически, это проявление сил упругости. Вес появляется в результате взаимодействия тела с опорой.

- В-третьих, вес зависит от ускорения, с которым движется опора. Если опора неподвижна (или движется равномерно и прямолинейно), то вес равен силе тяжести.

Последнее свойство показывает, что вес — это величина непостоянная, и может быть как меньше, так и больше силы тяжести, в зависимости от движения опоры.

Невесомость и перегрузки

Таким образом, вес без опоры не существует. Говорят, что тело, у которого нет опоры, находится в состоянии невесомости.

Обратите внимание, состояние невесомости не зависит от того, действует ли на тело гравитационная сила или нет. Предмет во время свободного падения, кабина лифта в момент начала спуска, когда натяжение троса исчезло, человек во время прыжка — всё это примеры состояния невесомости, которое появляется, несмотря на действие силы тяжести.

Из формулы веса тела следует, что если опора движется с ускорением, у тела появляется вес, который может быть даже больше, чем сила тяжести. В этом случае говорят о возникновении перегрузок.

Поскольку в формулу веса входит масса и сумма ускорения, перегрузку можно измерять в единицах $mathrm{g}$. Для нахождения перегрузки используется формула:

$$k= {m(mathrm{g} + a) over mmathrm{g}}=1+{aover mathrm{g}}$$

Фактически перегрузка показывает, во сколько раз вес тела больше силы тяжести, действующей на тело на Земле. Перегрузка $k=1$ означает обычный вес тела, перегрузка $k=2$ означает, что вес тела вдвое больше, чем сила тяжести и так далее.

Что мы узнали?

Вес тела — это сила, с которой тело действует на опору. Фактически это проявление силы упругости. Тело, у которого нет опоры, находится в состоянии невесомости. Если опора тела двигается с ускорением, тело испытывает перегрузки.

Тест по теме

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

Пока никого нет. Будьте первым!

Оценка доклада

4.2

Средняя оценка: 4.2

Всего получено оценок: 101.

А какая ваша оценка?