From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

VLT-SPHERE image of Pallas[1] |

|

| Discovery[2] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Heinrich Wilhelm Olbers |

| Discovery date | 28 March 1802 |

| Designations | |

|

MPC designation |

(2) Pallas |

| Pronunciation | [3] |

|

Named after |

Pallas Athena[4] |

|

Minor planet category |

Asteroid belt (central) Pallas family[5] |

| Adjectives | Palladian ()[6] |

| Symbol | |

| Orbital characteristics[7] | |

| Epoch 21 January 2022 (JD 2459600.5) | |

| Uncertainty parameter 0 | |

| Observation arc | 217 yr |

| Aphelion | 3.41 AU (510 Gm) |

| Perihelion | 2.13 AU (319 Gm) |

|

Semi-major axis |

2.77 AU (414 Gm) |

| Eccentricity | 0.23 |

|

Orbital period (sidereal) |

4.613 yr (1,684.9 d) |

|

Mean anomaly |

229.5 |

|

Mean motion |

0° 12m 46.8s / day |

| Inclination | 34.93° (34.43° to invariable plane)[8] |

|

Longitude of ascending node |

172.9° |

|

Argument of perihelion |

310.7° |

| Proper orbital elements[9] | |

|

Proper semi-major axis |

2.7709176 AU |

|

Proper eccentricity |

0.2812580 |

|

Proper inclination |

33.1988686° |

|

Proper mean motion |

78.041654 deg / yr |

|

Proper orbital period |

4.61292 yr (1684.869 d) |

|

Precession of perihelion |

−1.335344 arcsec / yr |

|

Precession of the ascending node |

−46.393342 arcsec / yr |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | c/a = 0.79±0.03[10] 568 ±12 km × 532 ±12 km × 448 ±12 km[11] 550 km × 516 km × 476 km[12] |

|

Mean diameter |

511±4[10] 513±6 km[11] 512±6 km[12] |

|

Surface area |

(8.3±0.2)×105 km2 (2020)[a][13] |

| Volume | (7.1±0.3)×107 km3 (2020)[a][14] |

| Mass | (2.04±0.03)×1020 kg average est.[11] (2.01±0.13)×1020 kg[b][15] |

|

Mean density |

2.92±0.08 g/cm3[10] 2.89±0.08 g/cm3[11] 2.57±0.19 g/cm3[15] |

|

Equatorial surface gravity |

≈0.21 m/s2 (average)[c] 0.022 g |

|

Equatorial escape velocity |

324 m/s[11] |

|

Synodic rotation period |

7.8132 h[16] |

|

Equatorial rotation velocity |

65 m/s[a] |

|

Axial tilt |

84°±5°[12] |

|

Geometric albedo |

0.155[10] 0.159[17] |

|

Spectral type |

B[7][18] |

|

Apparent magnitude |

6.49[19] to 10.65 |

|

Absolute magnitude (H) |

4.13[17] |

|

Angular diameter |

0.629″ to 0.171″[20] |

Pallas (minor-planet designation: 2 Pallas) is the second asteroid to have been discovered, after Ceres. It is believed to have a mineral composition similar to carbonaceous chondrite meteorites, like Ceres, though significantly less hydrated than Ceres. It is the third-largest asteroid in the Solar System by both volume and mass, and is a likely remnant protoplanet. It is 79% the mass of Vesta and 22% the mass of Ceres, constituting an estimated 7% of the mass of the asteroid belt. Its estimated volume is equivalent to a sphere 507 to 515 kilometers (315 to 320 mi) in diameter, 90–95% the volume of Vesta.

During the planetary formation era of the Solar System, objects grew in size through an accretion process to approximately the size of Pallas. Most of these protoplanets were incorporated into the growth of larger bodies, which became the planets, whereas others were ejected by the planets or destroyed in collisions with each other. Pallas, Vesta and Ceres appear to be the only intact bodies from this early stage of planetary formation to survive within the orbit of Neptune.[21]

When Pallas was discovered by the German astronomer Heinrich Wilhelm Matthäus Olbers on 28 March 1802, it was considered to be a planet,[22] as were other asteroids in the early 19th century. The discovery of many more asteroids after 1845 eventually led to the separate listing of «minor» planets from «major» planets, and the realization in the 1950s that such small bodies did not form in the same way as (other) planets led to the gradual abandonment of the term «minor planet» in favor of «asteroid» (or, for larger bodies such as Pallas, «planetoid»).

With an orbital inclination of 34.8°, Pallas’s orbit is unusually highly inclined to the plane of the asteroid belt, making Pallas relatively inaccessible to spacecraft, and its orbital eccentricity is nearly as large as that of Pluto.[23]

The high inclination of the orbit of Pallas results in the possibility of close conjunctions to stars that other solar objects always pass at great angular distance. This resulted in Pallas passing Sirius on 9 October 2022, only 8.5 arcminutes southwards,[24] while no planet can get closer than 30 degrees to Sirius.

History[edit]

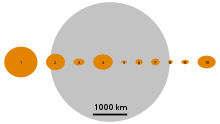

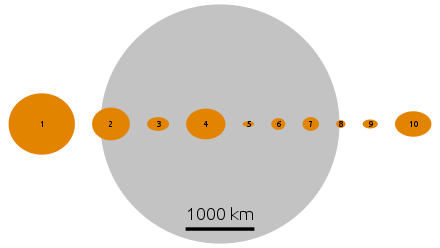

Size comparison: the first 10 asteroids profiled against the Moon. Pallas is number two.

Discovery[edit]

On the night of 5 April 1779, Charles Messier recorded Pallas on a star chart he used to track the path of a comet, now known as C/1779 A1 (Bode), that he observed in the spring of 1779, but apparently assumed it was nothing more than a star.[25]

In 1801, the astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi discovered an object which he initially believed to be a comet. Shortly thereafter he announced his observations of this object, noting that the slow, uniform motion was uncharacteristic of a comet, suggesting it was a different type of object. This was lost from sight for several months, but was recovered later that year by the Baron von Zach and Heinrich W. M. Olbers after a preliminary orbit was computed by Carl Friedrich Gauss. This object came to be named Ceres, and was the first asteroid to be discovered.[26][27]

A few months later, Olbers was again attempting to locate Ceres when he noticed another moving object in the vicinity. This was the asteroid Pallas, coincidentally passing near Ceres at the time. The discovery of this object created interest in the astronomy community. Before this point it had been speculated by astronomers that there should be a planet in the gap between Mars and Jupiter. Now, unexpectedly, a second such body had been found.[28] When Pallas was discovered, some estimates of its size were as high as 3,380 km in diameter.[29] Even as recently as 1979, Pallas was estimated to be 673 km in diameter, 26% greater than the currently accepted value.[30]

The orbit of Pallas was determined by Gauss, who found the period of 4.6 years was similar to the period for Ceres. Pallas has a relatively high orbital inclination to the plane of the ecliptic.[28]

Later observations[edit]

High-resolution images of the north (at left) and south (at right) hemispheres of Pallas, made possible by the Adaptive-Optics (AO)-fed SPHERE imager on the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in 2020.[31] Two large impact basins could have been created by asteroid family–forming impacts. The bright spot in the southern hemisphere is reminiscent of the salt deposits on Ceres.

In 1917, the Japanese astronomer Kiyotsugu Hirayama began to study asteroid motions. By plotting the mean orbital motion, inclination, and eccentricity of a set of asteroids, he discovered several distinct groupings. In a later paper he reported a group of three asteroids associated with Pallas, which became named the Pallas family, after the largest member of the group.[32] Since 1994 more than 10 members of this family have been identified, with semi-major axes between 2.50 and 2.82 AU and inclinations of 33–38°.[33] The validity of the family was confirmed in 2002 by a comparison of their spectra.[34]

Pallas has been observed occulting stars several times, including the best-observed of all asteroid occultation events, by 140 observers on 29 May 1983. These measurements resulted in the first accurate calculation of its diameter.[35][36]

After an occultation on 29 May 1979, the discovery of a possible tiny satellite with a diameter of about 1 km was reported, which was never confirmed.

Radio signals from spacecraft in orbit around Mars and/or on its surface have been used to estimate the mass of Pallas from the tiny perturbations induced by it onto the motion of Mars.[37]

The Dawn team was granted viewing time on the Hubble Space Telescope in September 2007 for a once-in-twenty-year opportunity to view Pallas at closest approach, to obtain comparative data for Ceres and Vesta.[38][39]

Name and symbol[edit]

‘Pallas’ (Ancient Greek: Παλλάς Ἀθηνᾶ) is an epithet of the Greek goddess Athena.[40][41] In some versions of the myth, Athena killed Pallas, daughter of Triton, then adopted her friend’s name out of mourning.[42]

The adjectival form of the name is Palladian.[6] The d is part of the oblique stem of the Greek name, which appears before a vowel but disappears before the nominative ending -s. The oblique form is seen in the Italian and Russian names for the asteroid, Pallade and Паллада (Pallada).[43]

The stony-iron pallasite meteorites are not Palladian, being named instead after the German naturalist Peter Simon Pallas. The chemical element palladium, on the other hand, was named after the asteroid, which had been discovered just before the element.[44]

The symbols for Ceres and Pallas, as published in 1802

The old astronomical symbol of Pallas, still used in astrology, is a spear or lance, ⟨⟩, one of the symbols of the goddess. The blade was most often a lozenge (◊), but various graphic variants were published, including an acute/elliptic leaf shape, a cordate leaf shape (♤:

), and a triangle (△); the last made it effectively the alchemical symbol for sulfur, ⟨

⟩.

The generic asteroid symbol of a disk with its discovery number, ⟨②⟩, was introduced in 1852 and quickly became the norm.[45][46] The iconic lozenge symbol was resurrected for astrological use in 1973.[47]

Orbit and rotation[edit]

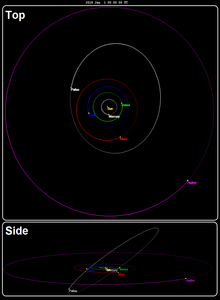

Pallas has a high eccentricity and a highly inclined orbit

Pallas has unusual dynamic parameters for such a large body. Its orbit is highly inclined and moderately eccentric, despite being at the same distance from the Sun as the central part of the asteroid belt. Furthermore, Pallas has a very high axial tilt of 84°, with its north pole pointing towards ecliptic coordinates (β, λ) = (30°, −16°) with a 5° uncertainty in the Ecliptic J2000.0 reference frame.[12] This means that every Palladian summer and winter, large parts of the surface are in constant sunlight or constant darkness for a time on the order of an Earth year, with areas near the poles experiencing continuous sunlight for as long as two years.[12]

Near resonances[edit]

Pallas is in a, likely coincidental, near-1:1 orbital resonance with Ceres.[48] Pallas also has a near-18:7 resonance (91,000-year period) and an approximate 5:2 resonance (83-year period) with Jupiter.[49]

-

Animation of the Palladian orbit in the inner Solar System

· Pallas

· Ceres

· Jupiter

· Mars

· Earth

· Sun -

An animation of Pallas’s near-18:7 resonance with Jupiter. The orbit of Pallas is green when above the ecliptic and red when below. It only marches clockwise: it never halts or reverses course (i.e. no libration). The motion of Pallas is shown in a reference frame that rotates about the Sun (the center dot) with a period equal to Jupiter’s orbital period. Accordingly, Jupiter’s orbit appears almost stationary as the pink ellipse at top left. Mars’s motion is orange, and the Earth–Moon system is blue and white.

Transits of planets from Pallas[edit]

From Pallas, the planets Mercury, Venus, Mars, and Earth can occasionally appear to transit, or pass in front of, the Sun. Earth last did so in 1968 and 1998, and will next transit in 2224. Mercury did in October 2009. The last and next by Venus are in 1677 and 2123, and for Mars they are in 1597 and 2759.[50]

Physical characteristics[edit]

Relative sizes of the four largest asteroids. Pallas is second from right.

Both Vesta and Pallas have assumed the title of second-largest asteroid from time to time.[51] At 513±3 km in diameter, Pallas is slightly smaller than Vesta (525.4±0.2 km[52]). The mass of Pallas is 79%±1% that of Vesta, 22% that of Ceres, and a quarter of one percent that of the Moon.

Pallas is farther from Earth and has a much lower albedo than Vesta, and hence is dimmer as seen from Earth. Indeed, the much smaller asteroid 7 Iris marginally exceeds Pallas in mean opposition magnitude.[53] Pallas’s mean opposition magnitude is +8.0, which is well within the range of 10×50 binoculars, but, unlike Ceres and Vesta, it will require more-powerful optical aid to view at small elongations, when its magnitude can drop as low as +10.6. During rare perihelic oppositions, Pallas can reach a magnitude of +6.4, right on the edge of naked-eye visibility.[19] During late February 2014 Pallas shone with magnitude 6.96.[54]

Pallas is a B-type asteroid.[12] Based on spectroscopic observations, the primary component of the material on Pallas’s surface is a silicate containing little iron and water. Minerals of this type include olivine and pyroxene, which are found in CM chondrules.[55] The surface composition of Pallas is very similar to the Renazzo carbonaceous chondrite (CR) meteorites, which are even lower in hydrous minerals than the CM type.[56] The Renazzo meteorite was discovered in Italy in 1824 and is one of the most primitive meteorites known.[57][d] Pallas’s visible and near-infrared spectrum is almost flat, being slightly brighter in towards the blue. There is only one clear absorption band in the 3-micron part, which suggests an anhydrous component mixed with hydrated CM-like silicates.[12]

Pallas’s surface is most likely composed of a silicate material; its spectrum and calculated density (2.89±0.08 g/cm3) correspond to CM chondrite meteorites (2.90±0.08 g/cm3), suggesting a mineral composition similar to that of Ceres, but significantly less hydrated.

To within observational limits, Pallas appears to be saturated with craters. Its high inclination and eccentricity means that average impacts are much more energetic than on Vesta or Ceres (with on average twice their velocity), meaning that smaller (and thus more common) impactors can create equivalently sized craters. Indeed, Pallas appears to have many more large craters than either Vesta or Ceres, with craters larger than 40 km covering at least 9% of its surface.

Pallas’ shape departs significantly from the dimensions of an equilibrium body at its current rotational period, indicating that it is not a dwarf planet.[12] It’s possible that a suspected large impact basin at the south pole, which ejected 6%±1% of the volume of Pallas (twice the volume of the Rheasilvia basin on Vesta), may have increased its inclination and slowed its rotation; the shape of Pallas without such a basin would be close to an equilibrium shape for a 6.2-hour rotational period. A smaller crater near the equator is associated with the Palladian family of asteroids.

Pallas probably has a quite homogeneous interior. The close match between Pallas and CM chondrites suggests that they formed in the same era and that the interior of Pallas never reached the temperature (≈820 K) needed to dehydrate silicates, which would be necessary to differentiate a dry silicate core beneath a hydrated mantle. Thus Pallas should be rather homogeneous in composition, though some upward flow of water could have occurred since. Such a migration of water to the surface would have left salt deposits, potentially explaining Pallas’s relatively high albedo. Indeed, one bright spot is reminiscent of those found on Ceres. Although other explanations for the bright spot are possible (e.g. a recent ejecta blanket), if the near-Earth asteroid 3200 Phaethon is an ejected piece of Pallas, as some have theorized, then a Palladian surface enriched in salts would explain the sodium abundance in the Geminid meteor shower caused by Phaethon.

Surface features[edit]

Besides one bright spot in the southern hemisphere, the only surface features identified on Pallas are craters. As of 2020, 36 craters have been identified, 34 of which are larger than 40 km in diameter. Provisional names have been provided for some of them. The craters are named after ancient weapons.

| Feature | Pronunciation | Latin or Greek | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Akontia | ἀκόντιον | dart | |

| Doru | δόρυ | pike | |

| Hoplon | ὅπλον | a weapon (esp. a large shield) | |

| Kopis | κοπίς | a large knife | |

| Sarissa | σάρισσα | lance | |

| Sfendonai | σφενδόνη | slingstone | |

| Toxa | τόξον | bow | |

| Xiphos | ξίΦος | sword | |

| Xyston | ξυστόν | spear |

| Feature | Pronunciation | Latin or Greek | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aklys | āclys | a small javelin attached to a strap | |

| Falcata | falcāta | a sword of pre-Roman Iberia | |

| Makhaira | μάχαιρα | a sword of ancient Greece | |

| Pilum | pīlum | a Roman javelin | |

| Scutum | scūtum | a Roman leather-covered shield | |

| Sica | sīca | a dagger | |

| Spatha | spatha | a straight sword |

Satellites[edit]

A small moon about 1 kilometer in diameter was suggested based on occultation data from 29 May 1978. In 1980, speckle interferometry suggested a much larger satellite, whose existence was later refuted a few years later with occultation data.[58]

Exploration[edit]

Pallas itself has never been visited by spacecraft. Proposals have been made in the past though none have come to fruition. A flyby of the Dawn probe’s visits to 4 Vesta and 1 Ceres was discussed but was not possible due to the high orbital inclination of Pallas.[59][60] The proposed Athena SmallSat mission would have been launched in 2022 as a secondary payload of the Psyche mission and travel on separate trajectory to a flyby encounter with 2 Pallas,[61][62] though was not funded due to being outcompeted by other mission concepts such as the Transorbital Trailblazer Lunar Orbiter. The authors of the proposal cited Pallas as the «largest unexplored» protoplanet with the main belt.[63][64]

Gallery[edit]

-

False-color image of Pallas

-

3D convex shape model from lightcurve inversion

-

3D convex shape model from lightcurve inversion

See also[edit]

- Objects formerly considered planets

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c Calculated using the known dimensions assuming an ellipsoid.

- ^ (1.010 ± 0.065) × 10−10 M☉

- ^ Calculated using the mean radius

- ^ Marsset 2020 finds it closer to CM meteorites

References[edit]

- ^ The craters covering Pallas, here only faintly discernible, are likely to look much sharper if the view were closer, as can be seen in this comparison of VLT and Dawn images of 4 Vesta.

- ^ «2 Pallas». Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- ^ «Pallas». Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ Schmadel, Lutz D. (2007). «(2) Pallas». Dictionary of Minor Planet Names. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. p. 15. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-29925-7_3. ISBN 978-3-540-00238-3.

- ^ «Asteroid 2 Pallas». Small Bodies Data Ferret. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- ^ a b «Palladian». Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ a b «JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 2 Pallas» (2018-01-23 last obs.). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- ^ Souami, D.; Souchay, J. (July 2012). «The solar system’s invariable plane». Astronomy & Astrophysics. 543: 11. Bibcode:2012A&A…543A.133S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201219011. A133.

- ^ «AstDyS-2 Pallas Synthetic Proper Orbital Elements». Department of Mathematics, University of Pisa, Italy. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- ^ a b c d P. Vernazza et al. (2021) VLT/SPHERE imaging survey of the largest main-belt asteroids: Final results and synthesis. Astronomy & Astrophysics 54, A56

- ^ a b c d e f g h Carry, B.; et al. (2009). «Physical properties of (2) Pallas». Icarus. 205 (2): 460–472. arXiv:0912.3626. Bibcode:2010Icar..205..460C. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2009.08.007. S2CID 119194526.

- ^ «Surface-area calculation using Wolfram Alpha».

- ^ «Volume calculation using Wolfram Alpha».

- ^ a b Baer, James; Chesley, Steven; Matson, Robert (2011). «Astrometric masses of 26 asteroids and observations on asteroid porosity». The Astronomical Journal. 141 (5): 143. Bibcode:2011AJ….141..143B. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/141/5/143.

- ^ «LCDB Data for (2) Pallas». Asteroid Lightcurve Database (LCDB). Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- ^ a b Tedesco, E. F.; Noah, P. V.; Noah, M.; Price, S. D. (October 2004). «IRAS Minor Planet Survey V6.0». NASA Planetary Data System. 12: IRAS-A-FPA-3-RDR-IMPS-V6.0. Bibcode:2004PDSS…12…..T. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ Neese, C., ed. (2005). «Asteroid Taxonomy. EAR-A-5-DDR-Taxonomy-V5.0». NASA Planetary Data System. Archived from the original on 5 August 2009. Retrieved 15 March 2007.

- ^ a b Menzel, Donald H.; Pasachoff, Jay M. (1983). A Field Guide to the Stars and Planets (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. p. 391. ISBN 978-0-395-34835-2.

- ^ Calculated with JPL Horizons for 1608-Feb-15

- ^ McCord, T. B.; McFadden, L. A.; Russell, C. T.; Sotin, C.; Thomas, P. C. (2006). «Ceres, Vesta, and Pallas: Protoplanets, Not Asteroids». Transactions of the American Geophysical Union. 87 (10): 105. Bibcode:2006EOSTr..87..105M. doi:10.1029/2006EO100002.

- ^ Hilton, James L. «When did the asteroids become minor planets?». Astronomical Applications Department. US Naval Observatory. Archived from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- ^ Anonymous. «Space Topics: Asteroids and Comets, Notable Comets». The Planetary Society. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- ^ Astrolutz 2022, ISBN 978-3-7534-7124-2

- ^ René Bourtembourg (2012). «Messier’s Missed Discovery of Pallas in April 1779». Journal for the History of Astronomy. 43 (2): 209–214. Bibcode:2012JHA….43..209B. doi:10.1177/002182861204300205. S2CID 118405076.

- ^ Hoskin, Michael (26 June 1992). «Bode’s Law and the Discovery of Ceres». Observatorio Astronomico di Palermo «Giuseppe S. Vaiana». Retrieved 5 July 2007.

- ^ Forbes, Eric G. (1971). «Gauss and the Discovery of Ceres». Journal for the History of Astronomy. 2 (3): 195–199. Bibcode:1971JHA…..2..195F. doi:10.1177/002182867100200305. S2CID 125888612.

- ^ a b «Astronomical Serendipity». NASA JPL. Archived from the original on 6 February 2012. Retrieved 15 March 2007.

- ^ Hilton, James L. (16 November 2007). «When did asteroids become minor planets?». U.S. Naval Observatory. Archived from the original on 21 September 2007. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ^ Hilton, James L. «Asteroid Masses and Densities» (PDF). U.S. Naval Observatory. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 August 2008. Retrieved 7 September 2008.

- ^ «Golf Ball World». Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ Kozai, Yoshihide (29 November – 3 December 1993). «Kiyotsugu Hirayama and His Families of Asteroids (invited)». Proceedings of the International Conference. Sagamihara, Japan: Astronomical Society of the Pacific. Bibcode:1994ASPC…63….1K.

- ^ Faure, Gérard (20 May 2004). «Description of the System of Asteroids». Astrosurf.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2007. Retrieved 15 March 2007.

- ^ Foglia, S.; Masi, G. (1999). «New clusters for highly inclined main-belt asteroids». The Minor Planet Bulletin. 31 (4): 100–102. Bibcode:2004MPBu…31..100F. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2007.

- ^ Drummond, J. D.; Cocke, W. J. (1989). «Triaxial ellipsoid dimensions and rotational pole of 2 Pallas from two stellar occultations» (PDF). Icarus. 78 (2): 323–329. Bibcode:1989Icar…78..323D. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.693.7435. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(89)90180-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 May 2011.

- ^ Dunham, D. W.; et al. (1990). «The size and shape of (2) Pallas from the 1983 occultation of 1 Vulpeculae». Astronomical Journal. 99: 1636–1662. Bibcode:1990AJ…..99.1636D. doi:10.1086/115446.

- ^ Pitjeva, E. V. (2004). «Estimations of masses of the largest asteroids and the main asteroid belt from ranging to planets, Mars orbiters and landers». 35th COSPAR Scientific Assembly. Held 18–25 July 2004, in Paris, France. p. 2014. Bibcode:2004cosp…35.2014P.

- ^ Schmidt, B.E.; Thomas, P.C.; Bauer, J.M.; Li, J.-Y.; McFadden, L.A.; Parker, J.M.; Rivkin, A.S.; Russell, C.T.; Stern, S.A. (2008). «Hubble takes a look at Pallas: Shape, size, and surface» (PDF). 39th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (Lunar and Planetary Science XXXIX). Held 10–14 March 2008, in League City, Texas. 1391 (1391): 2502. Bibcode:2008LPI….39.2502S. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 October 2008. Retrieved 24 August 2008.

- ^ Staff (24 October 2007). «Hubble Images of Asteroids Help Astronomers Prepare for Spacecraft Visit». JPL/NASA. Archived from the original on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 27 October 2007.

- ^ James, Andrew (1 September 2006). «Pallas». Southern Astronomical Delights. Retrieved 29 March 2007.

- ^ Freese, John Henry (1911). «Athena» . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 828.

- ^ Dietrich, Thomas (2005). The Origin of Culture and Civilization: The Cosmological Philosophy of the Ancient Worldview Regarding Myth, Astrology, Science, and Religion. Turnkey Press. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-9764981-6-2.

- ^ The one exception internationally to the use of the Greek stem for the name of the asteroid is Chinese, in which it is known as 智神星 (Zhìshénxīng), the ‘wisdom-god star’.

- ^ «Palladium». Los Alamos National Laboratory. Archived from the original on 5 April 2007. Retrieved 28 March 2007.

- ^ Forbes, Eric G. (1971). «Gauss and the Discovery of Ceres». Journal for the History of Astronomy. 2 (3): 195–199. Bibcode:1971JHA…..2..195F. doi:10.1177/002182867100200305. S2CID 125888612. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ Gould, B. A. (1852). «On the symbolic notation of the asteroids». Astronomical Journal. 2 (34): 80. Bibcode:1852AJ……2…80G. doi:10.1086/100212.

- ^ Eleanor Bach (1973) Ephemerides of the asteroids: Ceres, Pallas, Juno, Vesta, 1900–2000. Celestial Communications.

- ^ Goffin, E. (2001). «New determination of the mass of Pallas». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 365 (3): 627–630. Bibcode:2001A&A…365..627G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20000023.

- ^ Taylor, D. B. (1982). «The secular motion of Pallas». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 199 (2): 255–265. Bibcode:1982MNRAS.199..255T. doi:10.1093/mnras/199.2.255.

- ^ «Solex by Aldo Vitagliano». Archived from the original on 20 December 2008. Retrieved 19 March 2009. (numbers generated by Solex)

- ^ «Notable Asteroids». The Planetary Society. 2007. Archived from the original on 16 April 2007. Retrieved 17 March 2007.

- ^ Russell, C. T.; et al. (2012). «Dawn at Vesta: Testing the Protoplanetary Paradigm». Science. 336 (6082): 684–686. Bibcode:2012Sci…336..684R. doi:10.1126/science.1219381. PMID 22582253. S2CID 206540168.

- ^ Odeh, Moh’d. «The Brightest Asteroids». Jordanian Astronomical Society. Archived from the original on 13 August 2007. Retrieved 16 July 2007.

- ^ Calculated with JPL Horizons for 2014-Feb-24

- ^ Feierberg, M. A.; Larson, H. P.; Lebofsky, L. A. (1982). «The 3 Micron Spectrum of Asteroid 2 Pallas». Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 14: 719. Bibcode:1982BAAS…14..719F.

- ^ Sato, Kimiyasu; Miyamoto, Masamichi; Zolensky, Michael E. (1997). «Absorption bands near 3 m in diffuse reflectance spectra of carbonaceous chondrites: Comparison with asteroids». Meteoritics. 32 (4): 503–507. Bibcode:1997M&PS…32..503S. doi:10.1111/j.1945-5100.1997.tb01295.x. S2CID 129687767.

- ^ «Earliest Meteorites Provide New Piece in Planetary Formation Puzzle». Particle Physics and Astronomy Research Council. 20 September 2005. Archived from the original on 6 May 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2006.

- ^ Johnston, William Robert (5 March 2007). «Other Reports of Asteroid/TNO Companions». Johnson’s Archive. Archived from the original on 10 February 2007. Retrieved 14 March 2007.

- ^ Rayman, Marc (29 December 2014). «Ceres’ Curiosities: The Mysterious World Comes Into View». NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ Perozzi, Ettore; Rossi, Alessandro; Valsecchi, Giovanni B. (2001). «Basic targeting strategies for rendezvous and flyby missions to the near-Earth asteroids». Planetary and Space Science. 49 (1): 3–22. Bibcode:2001P&SS…49….3P. doi:10.1016/S0032-0633(00)00124-0.

- ^ Dorminey, Bruce (10 March 2019). «Proposed NASA SmallSat Mission Could Be First To Visit Pallas, Our Third Largest Asteroid». Forbes. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- ^ Athena: the first-ever encounter of (2) Pallas with a Smallsat. J. G. O’Rourke, J. Castillo-Rogez, L. T. Elkins-Tanton, R. R. Fu, T. N. Harrison, S. Marchi, R. Park, B. E. Schmidt, D. A. Williams, C. C. Seybold, R. N. Schindhelm, J. D. Weinberg. 50th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 2019 (LPI Contrib. No. 2132).

- ^ «Finalists Selected for NASA’s SIMPLEx Program». Planetary News. 24 June 2019. Archived from the original on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ «Athena: A SmallSat Mission to (2) Pallas». Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ Gingerich, Owen (16 August 2006). «The Path to Defining Planets» (PDF). Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and IAU EC Planet Definition Committee chair. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 March 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2007.

External links[edit]

Look up Pallas in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to (2) Pallas.

- Pallas at Encyclopædia Britannica, Edward F. Tedesco

- Mona Gable. «Study of first high-resolution images of Pallas confirms asteroid is actually a protoplanet». University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Archived from the original on 15 October 2009. Retrieved 20 October 2009.

- Jonathan Amos (11 October 2009). «Pallas is ‘Peter Pan’ space rock». BBC. Archived from the original on 19 July 2010. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- «2 Pallas». JPL Small-Body Database Browser. Retrieved 29 March 2007.

- Dunn, Tony (2006). «Ceres, Pallas Vesta and Hygeia». GravitySimulator.com. Archived from the original on 13 March 2007. Retrieved 15 March 2007.

- Hilton, James L. (1 April 1999). «U.S. Naval Observatory Ephemerides of the Largest Asteroids». U.S. Naval Observatory. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2007.

- Tedesco, Edward F.; Noah, Paul V.; Noah, Meg; Price, Stephan D. (2002). «The Supplemental IRAS Minor Planet Survey». The Astronomical Journal. 123 (2): 1056–1085. Bibcode:2002AJ….123.1056T. doi:10.1086/338320.

- 2 Pallas at AstDyS-2, Asteroids—Dynamic Site

- Ephemeris · Observation prediction · Orbital info · Proper elements · Observational info

- 2 Pallas at the JPL Small-Body Database

- Close approach · Discovery · Ephemeris · Orbit diagram · Orbital elements · Physical parameters

Дано:

a п = 2,77

e = 0,235

a⊕ = 1 а.е.

T⊕ = 1 год

g п = 0,194 м/с²

R п = 512 км = 512000 м

——————————————-

Найти:

q — ?

Q — ?

T п — ?

S п — ?

υ п — ?

Решение:

1) Запишем сначала формулы перигельное и афелийное расстояния:

(1) q = a(1-e) — перигельное расстояние

(2) Q = a(1+e) — афелийное расстояние

Далее мы их находим перигельное и афелийное расстояния:

q = 2,77 а.е. × (1-0,235) = 2,77 а.е. × 0,765 = 2,11905 а.е.

Q = 2,77 а.е. × (1+0,235) = 2,77 а.е. × 1,235 = 3,42095 а.е.

2) Теперь мы находим сидерический период обращения астероида Паллада, по третьему закону Кеплера:

T п²/T⊕² = a п³/a⊕³

Так как a⊕ = 1 а.е. , T⊕ = 1 год , следовательно мы получаем:

T п² = a п³ ⇒ T п = √a п³

Теперь решаем:

T п = √2,77³ = √21,253933 ≈ 4,61 года

3) Дальше мы находим синодеричечкий период обращения астероида Паллада для верхних по такой формуле:

1/S = 1/T⊕ — 1/T п ⇒ 1/S = T п — T⊕/T⊕×Tп

Следовательно мы получим:

S = T⊕×T п/Tп — T⊕

Далее считаем:

S = 1 год × 4,61 года/4,61 года — 1 год = 4,61 года/3,61 года ≈ 1,277 года

4) Теперь мы находим круговую скорость или как говорят первой космической скорости по такой формуле что бы найти скорость астероида Паллада:

υ п = √g п × R п

Теперь считаем:

υ п = √0,194 м/с² × 512000 м = √99328 м²/с² ≈ 315,16 м/с ≈ 0,31516 км/с

Ответ: q = 2,11905 а.е. ; Q = 3,42095 а.е. ; T п = 4,61 года ; S = 1,277 года ; υ п = 315,16 м/с или 0,31516 км/с.

Об омонимичных статьях см . Pallas .

(2) Паллада

Изображение Паллады, сделанное VLT [ 1 ] .

| Большая полуось ( а ) | 414 739 471 км (2,772 4 а.е. ) |

|---|---|

| Перигелий ( q ) | 319,358 × 106 км ( 2,135 а.е. ) |

| Афелия ( Q ) | 510,077 × 106 км ( 3,410 а.е. ) |

| Эксцентриситет ( е ) | 0,231 |

| Период оборота ( предыдущий ) | 1685,927 д |

| Средняя орбитальная скорость ( v orb ) | 17,65 км /с |

| Наклон ( я ) | 34,852 ° |

| Долгота восходящего узла ( Ω ) | 173,166 ° |

| Аргумент перигелия ( ω ) | 310,529 ° |

| Средняя аномалия ( M 0 ) | 346,022 ° |

| Категория | Астероид главного пояса |

| спутник | Солнце |

| Параметр Уивера ( T J ) | 3043 |

| Размеры | [(582 × 556 × 500) ± 18] км (545 ± 18) км (средний диаметр) |

|---|---|

| Масса ( м ) | (2,11 ± 0,26) × 10 20 кг |

| Плотность ( р ) | (2 490 + 600 — 400) кг/ м3 [ 2 ] |

| Экваториальная поверхностная гравитация ( g ) | 0,16 м /с 2 |

| Скорость выпуска ( v lib ) | 0,35 км / с _ |

| Период вращения ( P rot ) | 0,325 55 д |

| Спектральная классификация | Б |

| Абсолютная величина ( H ) | 4.13 |

| Альбедо ( А ) | 0,14 |

| Температура ( Т ) | ~ 164К |

| Самое раннее наблюдение до открытия | 6 апреля 1779 г. ( Шарль Мессье ) |

|---|---|

| Дата | 28 марта 1802 г. |

| Обнаружено | Генрих Ольберс |

| Названный в честь | Паллада ( эпиклеза греческой богини Афины ) |

| Имя | А802 ФА |

модифицировать

Паллада (от древнегреческого Παλλάς ), официально (2) Паллада , является третьим по величине объектом в главном поясе астероидов Солнечной системы , после карликовой планеты Цереры и астероида Веста . Это второй обнаруженный астероид. По счастливой случайности это был28 марта 1802 г.Генрих Ольберс , как астроном пытался найти Цереру , используя орбитальные предсказания Карла Фридриха Гаусса . Шарль Мессье , однако, был первым, кто наблюдал его в 1779 году, когда он проследил траекторию кометы , но он принял объект за простую звезду величиной 7 .

Паллада содержит около 7% всей массы пояса астероидов. Подобно Церере , Юноне и Весте , он считался планетой до тех пор, пока открытие множества других астероидов не привело к его реклассификации. Как и у Плутона, орбита Паллады очень круто наклонена (34,8 °) по отношению к плоскости главного пояса астероидов, что затрудняет доступ к астероиду космическим кораблям. Его поверхность состоит из силикатов , спектр которых подобен спектру углеродистых хондритовых метеоритов .

Фамилия

Астероид назван в честь Афины Паллады , эпиклезы Афины [ 3 ] , [ 4 ] означающей мудрую Афину . В некоторых версиях мифа Афина убила свою подругу Палладу , после чего в трауре приняла ее имя [ 5 ] . В греческой мифологии есть несколько мужских персонажей этого имени , но первым обнаруженным астероидам давались исключительно женские имена.

В греческом языке , в отличие от (1) Цереры , (3) Юноны и (4) Весты , астероид сохраняет то же имя, но уже греческое. Почти все другие языки используют тот или иной вариант Pallas : в итальянском Pallade , в русском Pallada , в испанском Palas , в арабском Bālās . Единственным исключением являются китайцы , которые называют ее «Звездой богини мудрости» 智神星 ( zhìshénxīng ). Это контрастирует с китайским именем богини Паллады, происходящим от греческого:帕拉斯( palāsī ).

Палласиты (класс метеоритов ) не имеют отношения к астероиду Паллада, а названы в честь немецкого натуралиста Петера Симона Палласа . Химический элемент палладий ( атомный номер 46 ) назван в честь астероида, открытого незадолго до этого [ 6 ] .

Первые обнаруженные астероиды имеют астрономический символ , а Паллада — .

История появления

Открытие

Предварительные открытия

Шарль Мессье наблюдает за Палласом6 апреля 1779 г., за 23 года до своего открытия отмечает его положение и считает его звездой [ 7 ] , [ 8 ] .

Марк-Антуан Парсеваль де Шенес , более чем за десять лет до открытия Ольберса, вычислил положение Паллады [ 9 ] .

Ольберс

В 1801 году астроном Джузеппе Пиацци открыл астероид, который сначала принял за комету. Вскоре после этого он объявил об открытии объекта, медленное и равномерное движение которого не соответствовало движению комет, и предположил, что это часть объекта нового типа. Этот объект был потерян на несколько месяцев, когда он прошел за Солнцем, а через несколько месяцев был найден бароном фон Заком и Генрихом В. М. Ольберсом благодаря расчету уменьшения орбиты, сделанному Фридрихом Гауссом . Его назвали Церера . Это первый обнаруженный астероид.

Несколько месяцев спустя, пытаясь определить местонахождение Цереры, Ольберс заметил присутствие движущегося объекта в том месте, где он должен был находиться. Это был астероид Паллада, случайно прошедший мимо Цереры. Открытие этого объекта вызвало интерес научной общественности. До открытия Цереры астрономы предполагали наличие планеты между орбитами Марса и Юпитера . Открытие второй планеты удивило их [ 10 ] .

Продолжение наблюдений

Орбита Паллады была рассчитана Гауссом, который нашел период в 4,6 года, аналогичный периоду Цереры. Однако Паллада имеет большое наклонение орбиты по отношению к плоскости эклиптики [ 10 ] .

В 1917 году японский астроном Киётсугу Хираяма начал изучать движение астероидов. Расположив астероиды по их среднему орбитальному движению, наклонению и эксцентриситету, он обнаружил несколько отдельных групп. В более поздней статье он сообщил об открытии группы из трех астероидов, связанных с Палласом, которые стали семейством Палласов после самого большого члена группы [ 11 ] . С 1994 г. обнаружено более десяти представителей этого семейства; его конечности имеют большую полуось между 2,50 и 2,82 а.е. и наклон между 33° и 38°) [ 12 ] . Существование этого семейства было окончательно подтверждено в 2002 г. путем сравнения их спектра [13 ] .

Исследования бельгийского астронома-любителя Рене Буртембура показали, что астероид впервые наблюдал Шарль Мессье .5 апреля 1779 г.поскольку он следовал траектории кометы Боде [ 14 ] . На нарисованной Мессье карте неба, показывающей траекторию движения кометы, астроном представляет 138 звезд, положение которых он сам измерил. Рене Буртамбур, благодаря компьютерной программе, способной находить точное положение звезд за тысячи лет, обнаруживает, что одна из звезд, представленных Мессье ( величина 7 ), на самом деле является астероидом Паллада. Шарль Мессье, сосредоточившийся на наблюдении за кометой, не обратил особого внимания на эту банальную на вид звезду и таким образом упустил открытие нового тела в Солнечной системе.

Всентябрь 2007 г., космический телескоп Хаббл производит новые данные о форме, величине и площади благодаря команде миссии Dawn , получающей время наблюдений от Хаббла; Паллада была тогда ближе всего к Земле, что случается только каждые 20 лет. Таким образом, были собраны данные, позволяющие проводить сравнения с Церерой и Вестой [ 15 ] , [ 16 ] .

Исследование

Запланированная базовая траектория для Dawn .

Как и у Плутона, орбита Паллады очень круто наклонена (34,8°) по отношению к плоскости главного пояса астероидов, что затрудняет доступ к астероиду космическим кораблям [ 17 ] . На самом деле Палладу еще не посещал такой аппарат, как зонд « Рассвет », который успешно исследовал (4) Весту и (1) Цереру . Орбита Паллады пересекает эклиптику вдекабрь 2018 г.но, учитывая значительный наклон орбиты Паллады, невозможно, чтобы Заря следовала за этой [ 18 ] . Миссия на Палладу, более сложная, чем облет, потребует космического корабля другой конструкции [ 19 ] .

В проекте определения планеты Международного астрономического союза 2006 года Паллада была среди «планет-кандидатов», но в конечном итоге не прошла квалификацию, так как не смогла очистить окрестности своей орбиты [ 20 ] , [ 21 ] . Если в будущем выяснится, что поверхность Паллады сформировалась в результате гидростатического равновесия , возможно, ее классификация будет изменена на карликовую планету .

Функции

Объем, масса и геология

Сравнение размеров: десятка самых больших астероидов по сравнению с Луной: Паллада — вторая слева.

Паллада содержит около 7% всей массы пояса астероидов [ 22 ] .

В свою очередь, Веста и Паллада носили титул второго по величине астероида [ 23 ] . На самом деле Паллада немного больше по объему, но, с другой стороны, значительно менее массивна: Паллада имеет 22% массы Цереры и 0,3% массы Луны.

Поверхность астероида известна очень мало. Изображения Хаббла 2007 года с разрешением ≈70 км показывают изменения от пикселя к пикселю, но альбедо 12% делает эти особенности едва заметными. В видимом и инфракрасном свете вариации невелики, но в ультрафиолете важные характеристики возможны в направлении 285°, то есть 75° западной долготы.

Считается, что у Паллады был период планетарной дифференциации [ 15 ] , что указывает на то, что она будет протопланетой . На этапе формирования планет Солнечной системы одни объекты росли путем аккреции , а другие разрушались в результате столкновений с другими. Паллада и Веста, вероятно, пережили эту раннюю стадию формирования планет [ 24 ] .

Состав

Согласно спектроскопическим наблюдениям , основными компонентами на поверхности Паллады являются маложелезистые и маловодные силикаты , такие как оливин и пироксен . В самом деле, инфракрасный спектр отражения напоминает спектр углистых хондритов типа CM ( Mighei ) [ 25 ] или даже CR ( Renazzo ), которые даже ниже в гидратированных минералах, чем у CM-типа [ 26 ] . Метеорит Ренаццо, обнаруженный в Италии в 1824 году, является одним из самых примитивных известных метеоритов .27 ] .

Величина

По сравнению с Вестой, Паллада находится дальше от Земли и имеет меньшее альбедо , поэтому кажется менее яркой. Даже (7) диафрагма , которая меньше, выглядит ярче [ 28 ] . Средняя звездная величина Паллады составляет +8,0 , что находится в пределах диапазона, наблюдаемого в бинокль 10 × 50 , но, в отличие от Цереры и Весты, требуется большая мощность наблюдения, когда удлинение Паллады минимально, потому что тогда ее звездная величина составляет +10,6. Во время перигеликальных противостояний Паллада может достигать звездной величины +6,4, что близко к видимости невооруженным глазом [ 29 ].] .

Конецфевраль 2014 г., Паллада имела (ранее рассчитанную) звездную величину 6,96 [ 30 ] .

Орбита

Анимация иллюстрирует квазирезонанс 18:7 с Юпитером , согласно вращающейся системе отсчета, вращающейся вокруг Солнца с тем же периодом, что и Юпитер, чья орбита, эллипс розового цвета, почти стационарна; Орбита Паллады зеленая, когда она находится над эклиптикой, и красная, когда она находится ниже; квазирезонанс 18:7 всегда по часовой стрелке, т.е. выпуска нет .

Параметры орбиты Паллады необычны для объекта такой массы. Его орбита имеет крутой наклон и довольно эксцентричен , несмотря на то, что находится на таком же расстоянии от Солнца, как и центр пояса астероидов . Его вращение выглядит прямолинейным [ 15 ] .

При этом наклон оси Палласа очень большой, 78±13° или 65±12°. По неоднозначным данным кривой блеска полюс указывает либо на эклиптические координаты (β, λ) = (−12°, 35°), либо (43°, 193°) с погрешностью 10° [ 31 ] . Данные 2007 г. с телескопа Хаббл, а также наблюдения с 2003 по 2005 гг. с телескопа Кека свидетельствуют в пользу первого решения [ 15 ] , [ 32 ] .. Другими словами, во все палладианские лета и зимы большие участки поверхности постоянно солнечные или постоянно погружаются во тьму на период времени порядка земного года.

Квазирезонансы

Паллада находится в квазирезонансе 1:1 с (1) Церерой [ 33 ] . Также и с Юпитером в квазирезонансе 18:7 с периодом 6500 лет и в квазирезонансе 5:2 с периодом 83 года [ 34 ] .

Транзиты планет, вид из Паллады

Как видно из Паллады, Меркурий, Венера, Марс и Земля иногда находятся в астрономическом транзите , то есть эти планеты проходят перед Солнцем. Так было для Земли в 1968 и 1998 годах, следующий раз будет в 2224 году. Для Меркурия последний раз был в 2009 году. Последний и следующий раз для Венеры соответственно в 1677 и 2123 году. Для Марса они были и будут происходят в 1597 и 2759 годах [ 35 ] .

Примечания и ссылки

- ↑ Кратеры на поверхности Паллады, которые едва видны здесь, вероятно, были бы гораздо более заметными, если бы их рассматривали с более высоким разрешением, как в случае этого сравнения изображений (4) Весты, сделанных VLT и зондом Dawn . .

- ↑ Рассчитано на основе средней массы и диаметра, указанных чуть выше. Неопределенность плотности рассчитывается из тех же значений и неопределенностей.

- ↑ Эндрю Джеймс , « Паллада » , Southern Astronomical Delights ,1 сентября 2006 г. (проконсультировался с29 марта 2007 г.) .

- ↑ « Афина » , издание Британской энциклопедии 1911 года , Британская энциклопедия (Тим Старлинг) ( доступно на 16 августа 2008 г.) .

- ↑ Томас Дитрих , Происхождение культуры и цивилизации: космологическая философия древнего мировоззрения в отношении мифов, астрологии, науки и религии , Turnkey Press,2005 г., 357 с. ( ISBN 0-9764981-6-2 ) , с. 178.

- ↑ «Палладий» , Лос-Аламосская национальная лаборатория (версия Интернет-архива от 6 декабря 2010 г. ) .

- ↑ « Шарль Мессье, первый наблюдатель астероида Паллада — Сиэль и Эспейс » , на www.cieletespace.fr

- ↑ Рене Буртембург, « Пропущенное Мессье открытие Паллады в апреле 1779 года » , Journal for the History of Astronomy , vol. 43, № 2 ,2012, с. 209–214 ( DOI 10.1177/002182861204300205 , Bibcode 2012JHA….43..209B )

- ↑ Парсеваль де Шенес «более чем за десять лет до открытия Паллады [ sic , следовательно, в 1792 году или раньше] объявил о появлении этой планеты в соответствии с постоянным изучением небесной области, где она находится. действительно показал в то время, когда он назначил его . Гратьен де Семюр, Трактат об ошибках и предубеждениях , Левавассер, 1843, с. 70 .

- ↑ a и b (en) « Astronomical Serendipity » , NASA JPL (консультации15 марта 2007 г.) .

- ↑ Ю. Кодзай , «Киёцугу Хираяма и его семьи астероидов (приглашены)» , в Proceedings of the International Conference , Sagamihara, Japan, Astronomical Society of the Pacific , 29 ноября — 3 декабря 1993 г. ( читать онлайн ).

- ↑ Жерар Фор, « Описание системы астероидов » , Astrosurf.com,20 мая 2004 г. (проконсультировался с15 марта 2007 г.) .

- ↑ С. Фолья и Г. Маси , « Новые скопления сильно наклоненных астероидов главного пояса » , The Minor Planet Bulletin , vol. 31.1999 г., с. 100-102 ( читать онлайн , доступ15 марта 2007 г.).

- ↑ Филипп Энарехос, « Шарль Мессье, первый наблюдатель астероида Паллада » , Cieletespace.fr,22 апреля 2011 г. (проконсультировался с23 апреля 2011 г.) .

- ↑ a b c и d (en) Б. Е. Шмидт , Томас , Бауэр , Ли , Макфадден , Матчлер , Паркер , Ривкин , Рассел и др. , « Хаббл смотрит на Палладу: форма, размер и поверхность » , Lunar and Planetary Science XXXIX , League City , Texas, vol. 1391 «39-я Лунная и планетарная научная конференция» , 10–14 марта 2008 г., с. 2502 ( Bibcode 2008LPI….39.2502S , читать онлайн [ архив4 октября 2008 г.] [PDF] , консультации по29 июня 2013 г.).

- ↑ « Изображения астероидов, полученные Хабблом, помогают астрономам подготовиться к посещению космического корабля » , JPL/NASA, 24 октября 2007 г. (проконсультировался с27 октября 2007 г.) .

- ↑ « Космические темы: астероиды и кометы, известные кометы » , Планетарное общество ( доступно 28 июня 2008 г.) .

- ↑ Этторе Пероцци , Алессандро Росси и Джованни Б. Вальсекки , « Основные стратегии наведения для сближения и пролёта к околоземным астероидам » , Planetary and Space Science , vol. 49, № 1 ,2001 г., с. 3–22 ( DOI 10.1016/S0032-0633(00)00124-0 , Bibcode 2001P&SS…49….3P ).

- ↑ Крис Рассел, Люси Макфадден, Джо Уайз или Марк Рэйман , « Часто задаваемые вопросы о миссии «Рассвет » , Лаборатория реактивного движения, 2011 (проконсультировался с15 сентября 2012 г.) .

- ↑ « Генеральная ассамблея IAU 2006: результат голосования за резолюцию IAU » , IAU ( доступ на 16 августа 2008 г.) .

- ↑ Пол Ринкон , « План Планет увеличивает число планет до 12 » , BBC News ,16 августа 2006 г. (проконсультировался с17 марта 2007 г.) .

- ↑ Е.В. Питьева ( 18 — 25 июля 2004 г.) « Оценки масс крупнейших астероидов и главного пояса астероидов от дальности до планет, марсианских орбитальных и спускаемых аппаратов » в 35-й Научной ассамблее КОСПАР . .

- ↑ « Известные астероиды » , Планетарное общество , 2007 г. (проконсультировался с17 марта 2007 г.) .

- ↑ TB McCord , LA McFadden , CT Russell , C. Sotin , and PC Thomas , « Церера, Веста и Паллада: протопланеты, а не астероиды » , Transactions of the American Geophysical Union , vol. 87, № 10 ,2006 г., с. 105 ( DOI 10.1029/2006EO100002 , Bibcode 2006EOSTr..87..105M ).

- ↑ М. А. Фейерберг , Х. П. Ларсон и Л. А. Лебофски , « 3-микронный спектр астероида 2 Паллада » , Бюллетень Американского астрономического общества , том. 14.1982 г., с. 719 ( Бибкод 1982BAAS…14..719F ).

- ↑ Кимиясу Сато , Масамичи Миямото и Майкл Э. Золенски , « Полосы поглощения вблизи 3 м в спектрах диффузного отражения углеродистых хондритов: сравнение с астероидами » , Meteoritics , vol. 32 , №4 ,1997 г., с. 503–507 ( DOI 10.1111/j.1945-5100.1997.tb01295.x , Bibcode 1997M&PS…32..503S ).

- ↑ « Самые ранние метеориты — новая часть головоломки формирования планет » . , Исследовательский совет по физике элементарных частиц и астрономии ,20 сентября 2005 г. (проконсультировался с24 мая 2006 г.) .

- ↑ Мох’д Оде, « Самые яркие астероиды » , Иорданское астрономическое общество (доступ 16 июля 2007 г.) .

- ↑ .(в) Дональд Х. Мензел и Джей М. Пасачофф , Полевой справочник по звездам и планетам , Бостон, Массачусетс, Хоутон-Миффлин,1983 г., 2- е изд . ( ISBN 0-395-34835-8 ) , с. 391.

- ↑ Значение рассчитано с помощью онлайн-инструмента « JPL Horizons » для24 февраля 2014 г..

- ↑ Дж. Торппа и др. , « Формы и вращательные свойства тридцати астероидов по фотометрическим данным » , Icarus , vol. 164, № 2 ,2003 г., с. 346–383 ( DOI 10.1016/S0019-1035(03)00146-5 , Bibcode 2003Icar..164..346T ).

- ↑ Б. Кэрри и др. , » Физические свойства астероида 2 Паллада на основе изображений с высоким угловым разрешением в ближнем инфракрасном диапазоне « [PDF] , 2007 г. (проконсультировался с22 июня 2009 г.) .

- ↑ Э. Гоффин , « Новое определение массы Паллады » , Astronomy and Astrophysics , vol. 365, № 3 ,2001 г., с. 627–630 ( DOI 10.1051/0004-6361:20000023 , Bibcode 2001A&A…365..627G ).

- ↑ Д.Б. Тейлор , » Вековое движение Паллады « , Королевское астрономическое общество , том . 199.1982 г., с. 255–265 ( Бибкод 1982MNRAS.199..255T ).

- ↑ (ru) » Страница Solex « (консультации по29 июня 2013 г.) (числа, сгенерированные Solex).

Смотрите также

Статьи по Теме

- Астероид

- пояс астероидов

- Список малых планет (1-1000)

- Церера

- Юнона

- Веста

- Список крупнейших астероидов главного пояса

внешние ссылки

- Ресурсы, связанные с астрономией

:

- (ru) Центр малых планет

- База данных моделей астероидов от методов инверсии

- База данных малых тел JPL

- (en) Характеристики и моделирование орбиты 2 в базе данных малых тел JPL . [Джава]

- База данных Центра малых планет

|

Малые планеты ( список ) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Предшествует | С последующим | |

|

(1) Церера |

(2) Паллада |

(3) Юнона |

Наша компания имеет богатый опыт сотрудничества и участия в тендерах с государственными и частными компаниями. Мы предлагаем большой набор готовых решений для образовательных учреждений, а также работаем по индивидуальным техническим заданиям.

Если вы являетесь участником или организатором тендера или госзакупки, заполните, пожалуйста, форму и опишите свой запрос. Наш специалист по работе с корпоративными заказчиками обязательно с вами свяжется. Вы также можете связаться с нами по телефону: +7 (812) 418-29-44 (доб. 117 или доб. 106).

Новости астрономии 2020

Гостевая книга

Астероид Паллада — самый крупный астероид

Наблюдения за астероидом Паллада

Исследования астероида Паллада

Астероид Паллада или (2) Pallas — второй по размеру объект в Главном поясе астероидов между орбитами Марса и Юпитера.

Названа в честь Паллады, дочери древнегреческой Афины.

Паллада была открыта 28 марта 1802 года немецким учёным Генрихом Вильгельмом Ольберсом в Бремене.

4 декабря 2017 года Паллада была сфотографирована с помощью европейской установки VLT/SPHERE, расположенной в горах Чили.

(источник снимка)

Среди астероидов Главного пояса Паллада является одним из крупнейших астероидов и уступает своими размерами только (1) Церере и (4) Весте,

Поскольку Цереру теперь относят к карликовым планетам, то Паллада является вторым по размеру астероидом между Марсом и Юпитером.

При этом, масса астероида Паллада составляет примерно 84% от массы (4) Весты», 22% от массы (1) Цереры и всего-лишь 0,3% от массы Луны.

На Палладу приходится около 7% массы Главного пояса астероидов.

| характеристика | значение |

|---|---|

| Диаметр | 550 ± 8 x 516 ± 6 x 476 ± 6 км |

| Масса | (2,11 ± 0,26)*1020 кг |

| Плотность | 3,0 ± 0,5 г/см3 |

| Ускорение свободного падения на поверхности | 0,194 м/с2 |

| Период вращения | 7,81 ч |

| Спектральный класс | B |

| Абсолютная звёздная величина | 4,13m |

| Альбедо | 0,1587 |

| Средняя температура поверхности | 164 °К (−109 °C) |

| характеристика | значение |

|---|---|

| Эксцентриситет (e) | 0,231 |

| Большая полуось (a) | 414,835 млн км (2,773 а. е.) |

| Перигелий (q) | 319,008 млн км (2,132 а. е.) |

| Афелий (Q) | 510,662 млн км (3,414 а. е.) |

| Период обращения (P) | 1686,643 суток (4,618 года) |

| Средняя орбитальная скорость | 17,645 км/с |

| Наклонение (i) | 34,838° |

Обращает на себя внимание довольно большой эксцентриситет орбиты Паллады — почти 35° к эклиптике

(или к плоскости орбит других планет, хоть и не хорошо так говорить, но упрощённо это так).

Эксцентриситет орбиты также довольно сильный — больше 0,231.

Всё это означает, что приполярные области Паллады около двух лет непрерывно освещаются Солнцем.

Но, это означает и обратное — полярные ночи на Палладе такие же длинные

Такая неправильность орбиты обычна для небольших астероидов, но для столь крупных тел как Паллада — нечастое явление.

Обращает на себя внимание периодическое сближение Паллады и Марса.

Как можно будет использовать такое движение Паллады, пока трудно сказать.

Но, довольно заманчиво иметь такой лифт для вывода объектов на более высокую орбиту

вокруг Солнца за счёт Паллады, одна из «остановок» которого располагается рядом с таким многообещающим объектом для колонизации, как Марс.

Наблюдения за астероидом Паллада

Невооружённым глазом Палладу увидеть можно во время противостояний c Землёй в перигелии, но только теоретически.

В это время видимая яркость Паллады достигает 6,4m.

Границей видимости человеческого глаза считается 6m, но при наличии отличного зрения и совершенно чёрном небе, она может увеличиваться почти до 7m.

Хотя, если честно, то толку от этого мало — объекты на границе видимости видны очень неустойчиво.

Гораздо проще взять бинокль — любая модель уверенно покажет и Палладу и множество других менее ярких объектов.

Исследования астероида Паллада

Исследований Паллады пока не проводилось, ни одна исследовательская станция не приближалась к этому астероиду.

Но, в 2022 году, агентством NASA запланировано исследование астероида Паллада автоматической станцией «Афина».

Предусмотрено фотографирование поверхности Паллады, а так же радиологический эксперимент,

в ходе которого с помощью двунаправленной антенны будет определена масса Паллады с точностью <0,05% (источник)

Текущее положение Паллады и других самых заметных небесных тел смотрите на странице Карта неба онлайн.

Ещё по этой теме:

Астероид Гигея

Макемаке — карликовая планета

или расскажите друзьям:

При перепечатке материалов с этого сайта, ссылка на kosmoved.ru обязательна.

© Copyright 2014-2020, kosmoved.ru

Контакты: info@kosmoved.ru