IV. ЛАБОРАТОРНАЯ РАБОТА: ОПРЕДЕЛЕНИЕ МАССЫ ЯДРА ДЕЙТЕРИЯ ПО РАЗНОСТИ ДЛИН ВОЛН ЛИНИЙ H® È D®, ИЗМЕРЯЕМОЙ ПРИ ПОМОЩИ ИНТЕРФЕРОМЕТРА МАЙКЕЛЬСОНА

Введение

Волновые числа спектральных линий водорода, как известно, могут быть получены из формулы Бальмера:

|

º = Rµn2 |

¡ m2 |

¶; |

(10) |

|

1 |

1 |

значения чисел n определяют серии, и числа m номера линий в серии. Так, например, значению n = 2

соответствует серия Бальмера, расположенная в видимой и близкой ультрафиолетовой областях спектра; числа m = 3; 4; 5 дают соответственно линии H®, H¯ è H° этой серии.

Постоянная Ридберга включает в себя комбинацию известных постоянных, а именно:

|

R = |

2¼2e4m |

; |

(11) |

||||

|

ch4 |

|||||||

|

ãäå m = |

m0 |

— приведенная масса, m0 масса электрона и M масса ядра. |

|||||

|

1+ |

m0 |

||||||

|

M |

|||||||

Приведенная масса m в выражении (11) учитывает влияние движения ядра и электрона вокруг их общего центра тяжести на значение энергии атома, а, следовательно, и на значениеR.

|

Таким образом, атомы, отличающиеся друг от друга лишь массой ядер (изотопы), будут давать спектры, |

||||

|

сходные по сериальному расположению линий, но волновые числа, а следовательно и длины волн соответствую- |

||||

|

щих линий будут различны: они будут сдвинуты относительно друг друга. Такой сдвиг наблюдается, например, |

||||

|

в спектре изотопа водорода дейтерия. Линии дейтерия сдвинуты относительно линий обычного водорода. |

||||

|

Частоты линий водорода и дейтерия выражаются формулами: |

µn2 |

¡ m2 ¶: |

||

|

ºH = RHµn2 |

¡ m2 ¶; |

ºD = RD |

||

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

Для линий водорода и дейтерия, возникающих при одинаковом квантовом переходе (когдаn è m для обоих атомов), можно написать соотношение:

|

¸ |

= |

¸H ¡ ¸D |

= |

ºD ¡ ºH |

= |

RD ¡ RH |

: |

||||

|

¸H |

¸H |

ºD |

RD |

||||||||

|

RD è RH можно выразить через постоянную Ридберга для атома с бесконечной массойR1: |

|||||||||||

|

RH = R1 |

MH |

||||||||||

|

è |

MH + m0 |

||||||||||

|

RD = R1 |

MD |

; |

|||||||||

|

MD + m0 |

ãäå MH è MD обозначают массы ядер обычного водорода дейтерия, аm0 — массу электрона. Отсюда получим:

|

RD |

MD |

µMD + m0 |

¡ MH + m0 ¶ |

¡ 1 + MH |

||||||

|

RD ¡ RH |

MD + m0 |

MD |

MH |

1 + |

m0 |

|||||

|

= |

= 1 |

m0 |

|

Ввиду малости отношения |

m0 |

= |

1 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

1836 можно приближенно положить |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

MH |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

m0 |

¡1 |

m0 |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

µ1 + |

¶ |

= 1 ¡ |

: |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

MH |

MH |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Тогда |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

RD ¡ RH |

= |

m0 |

m0 |

+ |

m0 m0 |

= |

m0 |

m0 |

1 |

m0 |

:labeleq : h15e4 |

(13) |

||||||||||||

|

MH |

MD mH |

MH |

¡ MD |

¡ MH |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

RD |

¡ MD |

µ |

¶ |

Последнюю скобку можно приближенно считать единицей, и тогда, подставляя выражение (12) в (??), получим:

|

¸ |

= |

m0 |

¡ |

m0 |

: |

(14) |

||

|

¸H |

MH |

MD |

||||||

|

Из выражения (14) следует, что, зная MD, мы можем определить |

¸, поскольку остальные величины известны; |

и наоборот: измерив ¸можно определить массу ядра дейтерия. Второй случай и составляет задачу настоящей работы. Из формулы (14)имеем:

|

MD = |

m0 |

(15) |

|||

|

m0 |

¡ |

¸ |

|||

|

MH |

¸H |

Для вычисления MD можно воспользоваться следующими табличными значениями постоянных:

|

масса электрона |

m |

0 |

= |

9; 109 |

¢ |

10¡28 |

ã. |

||

|

масса протона |

1; 6723 |

10¡24 |

ã. |

||||||

|

MH = |

¢ |

||||||||

|

Длина волны красной линии (H®) обычного водорода |

|||||||||

|

¸H® = 6562; 80 A: |

|||||||||

|

Примечание: Замена значения скобки µ1¡ MH ¶ |

единицей даст ошибку, составляющую около 0,05% вычис- |

||||||||

|

m0 |

|

ляемой величины. |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Если относительная погрешность экспериментально определяемой величины ¸ ниже этого значения или |

||||||||||||||||||

|

даже одного с ним порядка, то описанного упрощения делать не следует. В этом случае в разложении |

||||||||||||||||||

|

µ |

MH |

¶ |

¡1 |

¡ MH |

MH2 |

|||||||||||||

|

m |

m |

0 |

m2 |

|||||||||||||||

|

1 + |

0 |

= 1 |

+ |

0 |

+ : : : |

|||||||||||||

|

надо еще квадратичный член. Тогда формулой, дающей большую степень приближения, будет |

||||||||||||||||||

|

1 ¡ |

m0 |

|||||||||||||||||

|

MD = m0 |

MH |

(16) |

||||||||||||||||

|

m0 |

m0 |

¸ |

||||||||||||||||

|

MH |

³1 ¡ |

MH |

´ |

¡ ¸H |

12 t; 32 t и т.д., одна система колец будет распо-

|

Измерение длин волн с помощью интерферометра Майкельсона |

||||

|

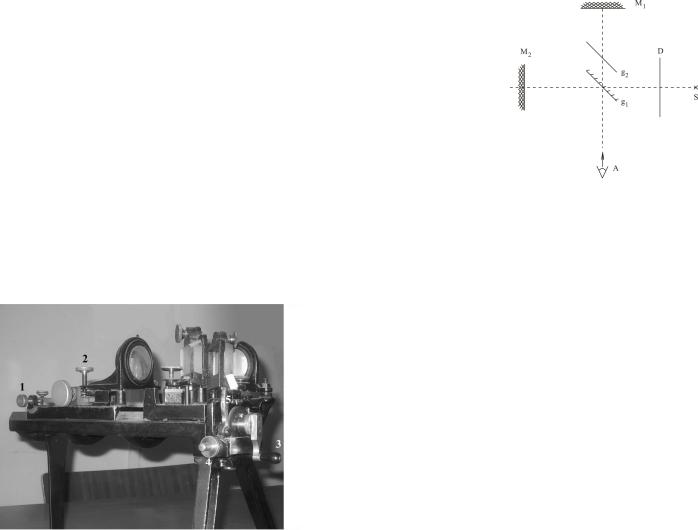

Схема интерферометра представлена на Рис. IV. Свет от источника S, про- |

||||

|

ходящий через линзу L, идет далее в виде параллельного пучка. Попадая на |

||||

|

плоскопараллельную стеклянную пластинку g1, задняя поверхность которой |

||||

|

представляет собой полупрозрачное стекло, пучок разделяется на два взаим- |

||||

|

но перпендикулярных пучка I и II. |

||||

|

Пучок I попадает нормально на плоское зеркало M1, отражается обратно и |

||||

|

снова разделяется полупрозрачным зеркалом g1 на два пучка½ один из кото- |

||||

|

рых идет в направлении А, где помещается глаз наблюдателя, а второй идет |

||||

|

обратно по направлению к линзе L и в дальнейшем не представляет интере- |

||||

|

са. Пучок II падает нормально на плоское зеркало M2. С помощью салазок и |

||||

|

винта Рис. IV, ручка (3) это зеркало может перемещаться вдоль направления |

||||

|

пучка, оставаясь строго параллельным самому себе. Отражаясь от зеркала |

||||

|

M2, пучок идет обратно и снова разделяется полупрозрачным зеркалом на |

||||

|

два пучка, из которых пучок, идущий к линзе, опять не представляет инте- |

||||

|

реса; второй пучок также идет по направлению А. Допустим теперь, что на |

||||

|

интерферометр одновременно подают два монохроматических пучка с дли- |

||||

|

Ðèñ. 19. |

íàìè âîëí ¸ è ¸0 = ¸ + ¸. Кольца, соответствующие обеим линиям, будут |

|||

|

совпадать при выполнении условия: |

||||

|

k¸ = (k + k0)¸0 = 2t; |

(17) |

|||

|

ãäå k è k0 — целые числа. При выполнении же условия |

||||

|

1 |

||||

|

k¸ = µk + k0 + |

¶¸0 = 2t |

(18) |

||

|

2 |

кольца, соответствующие длине волны ¸, расположатся посередине между кольцами, соответствующими длине волны ¸0, и вся интерференционная картина будет смазана. Таким образом, интерферометр Майкельсона не поз-

воляет наблюдать раздельно интерференционные полосы даже в простейшем случае двух монохроматических линий. Представление о составе падающего на интерферометр света может быть получено лишь при наблюдении

изменений картины, происходящих при передвижении зеркала M2.

Полагая по-прежнему для простоты, что на интерферометр падают две строго монохроматические волны с длинами волн ¸ è ¸0, поставим зеркало M2 на таком расстоянии t0 от плоскости N, чтобы обе системы колец

совпадали; при этом t0 должно удовлетворять условию:

|

2t0 = k¸ = (k + k0)¸ |

(19) |

|||||||||||||

|

При увеличении расстояния t0 íà t кольца снова совпадут, если |

||||||||||||||

|

2 (t0 + t) = (k + k00) ¸ = (k + k0 + k00) ¸0; |

(20) |

|||||||||||||

|

ãäå k00 — целое число. |

¸, получим: |

|||||||||||||

|

Почленно вычитая равенства (19) и (refeq:h15e11) друг из друга и замечая, что¸0 = ¸ |

¡ |

|||||||||||||

|

¸ = |

¸ |

; k00 = |

2Δt |

: |

||||||||||

|

k00 |

+ 1 |

¸ |

||||||||||||

|

Пренебрегая 1 по сравнению с k00, найдем: |

||||||||||||||

|

t = |

¸2 |

¸ = |

¸2 |

|||||||||||

|

2Δ¸ |

s t |

(21) |

||||||||||||

При увеличении расстояния между зеркалами на 2Δt; 3Δt и т.д., кольца снова будут совпадать.

Также легко видеть, что при увеличении расстояния t0 íà лагаться между другой.

Разность расстояний между двумя соседними положениями зеркала M2, при которых интерференционная картина размывается, выражается также формулой (21); доказательство этого предлагается проделать самостоятельно.

Таким образом, при постепенном отодвигании зеркала M2, интерференционная картина периодически будет то делаться резкой, то размываться, причем период определяется отрезком t, даваемым формулой (21).

Экспериментально определяя значение t, можно определить ¸ по формуле (21).

Ðèñ. 20.

Установка интерферометра и практические указания к работе

1. В рабочем положении зеркала интерферометра должны быть установлены так, чтобы зеркало M2 и получающееся после отражения от пластинки мнимое

изображение зеркала M1 (обозначим его M), были строго параллельны друг другу.

Для того, чтобы интерференционная картина легко находилась, необходимо

также сделать расстояние между зеркалами M1 è M2 достаточно малым. Предварительная установка интерферометра в это положение производится

следующим образом: интерферометр освещают каким-либо источником света с резкими очертаниями. Для этого можно воспользоваться простой неоновой лампой, можно также, для большей точности, поставить перед лампой диафрагму с крестообразной прорезью. При положении глаза, указанном на Рис. IV, бу-

дут видны два изображения источника отражения в зеркалах M1 è M2. Вращая

установочные винты зеркала M2, добиваются совмещения этих изображений. Очевидно, что добиться совмещения можно только тогда, когда зеркала находятся на одинаковом расстоянии от источника света (и от глаза). Если это не так, то изображения источника находятся в разных плоскостях, и тогда при перемещении глаза в поперечном направлении Рис. IV, относительное расположение изображений меняется (параллакс). Для уничтожения параллакса надо при по-

мощи микрометрического винта (рычаг 5 должен быть поставлен в нижнее положение!) установить зеркало M2

так, чтобы расстояния M2g1 è M1g2 были примерно равны.

Примечание:

а) При установке интерферометра ни в коем случае не следует пользоваться винтами пластинок g1 è g2 и зеркала

|

M1, т.к. пластинки g1 è g2 и зеркало M1 уже установлены |

|

|

б) Следует помнить, что посеребренынаружные поверх- |

|

|

ности зеркал и пластинки g1; всякое прикосновение к их |

|

|

поверхности выводит прибор из строя. |

|

|

2. Если предварительная установка зеркала M2 выпол- |

|

|

нена достаточно тщательно, что в направлении А (см. |

|

|

Рис. IV) на фоне изображения светящегося пятачка лампы |

|

|

должна быть видна интерференционная картина, но по- |

|

|

лосы будут, вероятно, очень мелкими. Пользуясь линзой, |

|

|

добиваются, чтобы все поле зрения было заполнено светом |

|

|

(освещают интерферометр параллельным пучком). |

|

|

Осторожным вращением винтов тонкой настройки зер- |

|

|

êàëà M2 и вращением микрометрического винта добива- |

|

|

ются, чтобы в поле зрения был виде центр интерференци- |

|

|

онной картины (зеркала M1 è M2 параллельны), и чтобы |

|

|

полосы были крупными (расстояние между зеркалами ма- |

|

|

Ðèñ. 21. Внешний вид прибора. 1, 2 установоч- |

ëî). |

|

ные винты зеркала M2; 3 маховичок; 4 бара- |

3. Заменяют неоновую лампу разрядной трубкой, кото- |

|

банчик; 5 рычаг, включающий барабанчик. |

рая заполнена смесью водорода и дейтерия. Без фильтра |

|

должны быть видны голубые кольца на розовом фоне; ес- |

|

|

ли колец не видно, то следует несколько изменить рассто- |

ÿíèå M2g1, вращая маховичок микрометрического винта (не более 2,5 оборотов в ту и в другую сторону). Затем между линзой и трубкой ставят красный фильтр, и, осторожно действуя установочными винтами зеркала, добиваются, чтобы в поле зрения был бы виден центр интерференционной картины, и кольца вблизи центра были бы достаточно крупными.

t определяется следующим образом. Устанавливают интерферометр в положение наибольшей резкости колей

или наибольшего смазывания их. Записывают показания на маховичке микрометрического винта и показания добавочного барабанчика. Затем вращают микрометрический винт и отмечают положение, когда картина повторяется, т.е. имеет место либо наибольшая резкость, либо наибольшая размытость. Разность двух соседних положений зеркала M2 и даст период t.

При измерении t следует отсчитывать полные обороты маховичка, показания шкалы на нем (цена деления

0,01 оборота) и показания добавочного барабанчика (цена деления 0,0002 оборота). Шаг винта — 0,5 мм. Слева от маховичка (3) имеется рычаг (5), включающий барабанчик (4). Включать барабанчик нужно только при измерениях.

Положение максимального смазывания картины устанавливается точнее, чем положение максимальной резкости, поэтому следует определять t по смазыванию картины.

5. Для наблюдения интерференционной картины, даваемой линиямиH® è D®, следует употреблять красный фильтр, позволяющий отделить эти линии от других линий спектра. При вычислении ¸ из выражения (21),

çà ¸ следует принимать длину волны H®, которую рекомендуется вычислять по формуле (10).

Литература

1.Фриш С.Э., Техника спектроскопии, Л., 1936.

2.Фриш С.Э., Оптические спектры атомов, М., 1963

Задание

1.Пользуясь неоновой лампочкой, установить интерферометр и получить четкую интерференционную картину.

2.Осветив интерферометр газоразрядной трубкой, определить разности длин волнH® è D®, H° è D°; äëÿ выделения нужных линий надо использовать светофильтры.

Перед включением трубки необходимо включить охлаждающий трубку вентилятор. Трубка питается от высокочастотного генератора. Включив генератор, надо дать прогреться лампам 3 5 минут, после чего трубка зажигается с помощью трансформатора Тесла. При этом ни в коем случае нельзя подавать разряд на электроды высокочастотного генератора — будет пробит конденсатор!!

3. По найденным разностям ¸® è ¸° вычислить массу ядра дейтерия.

¸(H®) = 6562; 85A ¸(H°) = 4340; 47A

Задание

1.Дать оптическую схему установки с указанием хода лучей.

2.Привести таблицу измерений t.

3.Привести результаты вычисления ¸ с оценкой погрешностей их определения.

4.Привести полученное значение MD с оценкой погрешности.

Выбрать другой вопрос

Смотреть ответ

Перейти к выбору ответа

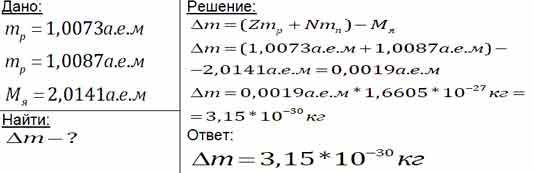

Вопрос от пользователя

Определите дефект масс ядра изотопа дейтерия 2 1Н (тяжёлого водорода). Масса протона приблизительно равна 1,0073 а.е.м., нейтрона 1,0087 а.е.м., ядра дейтерия 2,0141 а.е.м., 1 а.е.м. = 1,66 • 10^~27 кг

Ответ от эксперта

ответ к заданию по физике

Доброго времени суток. Решал задачку, и в условии было сказано, что необходимо найти массы дейтерия и трития для изготовления водородной бомбы, имеющей тротиловый эквивалент 100 килотонн. Из условия известно, что тепловой эффект тротила равен q=4,1*10^6 Дж/кг. Я нашел энергию, выделяющуюся при взрыве тротила (сделав допущение, что вся энергия переходит в тепловую): Q=m*q=100 килотонн*4,1*10^6 Дж/кг=4,1*10^14 Дж. А дальше я задумался, как найти массы дейтерия и трития. Буду весьма благодарен за подсказку, формулу или что-либо наводящее на верное решение.

Заряд ядра любого изотопа элемента постоянен, собственно он и характеризует элемент. Различные изотопы одного и того же элемента отличаются количеством нейтральных по заряду нейтронов в ядре. Так для водорода известно три изотопа: протий, дейтерий и тритий. У всех у них заряд ядра +1 (в единицах элементарного заряда). Масса протия равна 1 (в атомных единицах массы), так как его ядро состоит из единственного протона, дейтерий помимо протона включает нейтрон — масса ядра дейтерия равна 2, тритий включает в себя протон и два нейтрона его масса равна 3.

Deuterium isotope highlighted on a truncated table of nuclides for atomic numbers 1 through 29. Number of neutrons starts at zero and increases downward. Number of protons starts at one and increases rightward. Stable isotopes in blue. |

|

| General | |

|---|---|

| Symbol | 2H |

| Names | Deuterium, hydrogen-2, 2 H , 2H, H-2, hydrogen-2, D, 2 H |

| Protons (Z) | 1 |

| Neutrons (N) | 1 |

| Nuclide data | |

| Natural abundance | 0.0156% (Earth)[1] |

| Isotope mass | 2.01410177811[2] Da |

| Spin | 1+ |

| Excess energy | 13135.720±0.001 keV |

| Binding energy | 2224.52±0.20 keV |

| Isotopes of hydrogen Complete table of nuclides |

Deuterium (or hydrogen-2, symbol 2

H

or D, also known as heavy hydrogen) is one of two stable isotopes of hydrogen (the other being protium, or hydrogen-1). The nucleus of a deuterium atom, called a deuteron, contains one proton and one neutron, whereas the far more common protium has no neutrons in the nucleus. Deuterium has a natural abundance in Earth’s oceans of about one atom of deuterium among every 6,420 atoms of hydrogen (see heavy water). Thus deuterium accounts for approximately 0.0156% by number (0.0312% by mass) of all the naturally occurring hydrogen in the oceans, while protium accounts for more than 99.98%. The abundance of deuterium changes slightly from one kind of natural water to another (see Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water). (Tritium is yet another hydrogen isotope with symbol 3

H

or T. It has two neutrons, and is radioactive and far more rare than deuterium.)

The name deuterium is derived from the Greek deuteros, meaning «second», to denote the two particles composing the nucleus.[3] Deuterium was discovered by American chemist Harold Urey in 1931. Urey and others produced samples of heavy water in which the deuterium content had been highly concentrated. The discovery of deuterium won Urey a Nobel Prize in 1934.

Deuterium is destroyed in the interiors of stars faster than it is produced. Other natural processes are thought to produce only an insignificant amount of deuterium. Nearly all deuterium found in nature was produced in the Big Bang 13.8 billion years ago, as the basic or primordial ratio of hydrogen-1 to deuterium (about 26 atoms of deuterium per million hydrogen atoms) has its origin from that time. This is the ratio found in the gas giant planets, such as Jupiter. The analysis of deuterium–protium ratios in comets found results very similar to the mean ratio in Earth’s oceans (156 atoms of deuterium per million hydrogen atoms). This reinforces theories that much of Earth’s ocean water is of cometary origin.[4][5] The deuterium–protium ratio of the comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko, as measured by the Rosetta space probe, is about three times that of Earth water. This figure is the highest yet measured in a comet.[6]

Deuterium–protium ratios thus continue to be an active topic of research in both astronomy and climatology.

Differences from common hydrogen (protium)[edit]

Chemical symbol[edit]

Deuterium is frequently represented by the chemical symbol D. Since it is an isotope of hydrogen with mass number 2, it is also represented by 2

H

. IUPAC allows both D and 2

H

, although 2

H

is preferred.[7] A distinct chemical symbol is used for convenience because of the isotope’s common use in various scientific processes. Also, its large mass difference with protium (1H) (deuterium has a mass of 2.014102 u, compared to the mean hydrogen atomic weight of 1.007947 u, and protium’s mass of 1.007825 u) confers non-negligible chemical dissimilarities with protium-containing compounds, whereas the isotope weight ratios within other chemical elements are largely insignificant in this regard.

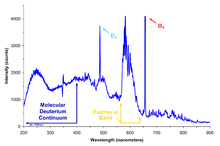

Spectroscopy[edit]

In quantum mechanics the energy levels of electrons in atoms depend on the reduced mass of the system of electron and nucleus. For the hydrogen atom, the role of reduced mass is most simply seen in the Bohr model of the atom, where the reduced mass appears in a simple calculation of the Rydberg constant and Rydberg equation, but the reduced mass also appears in the Schrödinger equation, and the Dirac equation for calculating atomic energy levels.

The reduced mass of the system in these equations is close to the mass of a single electron, but differs from it by a small amount about equal to the ratio of mass of the electron to the atomic nucleus. For hydrogen, this amount is about 1837/1836, or 1.000545, and for deuterium it is even smaller: 3671/3670, or 1.0002725. The energies of spectroscopic lines for deuterium and light hydrogen (hydrogen-1) therefore differ by the ratios of these two numbers, which is 1.000272. The wavelengths of all deuterium spectroscopic lines are shorter than the corresponding lines of light hydrogen, by a factor of 1.000272. In astronomical observation, this corresponds to a blue Doppler shift of 0.000272 times the speed of light, or 81.6 km/s.[8]

The differences are much more pronounced in vibrational spectroscopy such as infrared spectroscopy and Raman spectroscopy,[9] and in rotational spectra such as microwave spectroscopy because the reduced mass of the deuterium is markedly higher than that of protium. In nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, deuterium has a very different NMR frequency (e.g. 61 MHz when protium is at 400 MHz) and is much less sensitive. Deuterated solvents are usually used in protium NMR to prevent the solvent from overlapping with the signal, although deuterium NMR on its own right is also possible.

Big Bang nucleosynthesis[edit]

Deuterium is thought to have played an important role in setting the number and ratios of the elements that were formed in the Big Bang. Combining thermodynamics and the changes brought about by cosmic expansion, one can calculate the fraction of protons and neutrons based on the temperature at the point that the universe cooled enough to allow formation of nuclei. This calculation indicates seven protons for every neutron at the beginning of nucleogenesis, a ratio that would remain stable even after nucleogenesis was over. This fraction was in favor of protons initially, primarily because the lower mass of the proton favored their production. As the Universe expanded, it cooled. Free neutrons and protons are less stable than helium nuclei, and the protons and neutrons had a strong energetic reason to form helium-4. However, forming helium-4 requires the intermediate step of forming deuterium.

Through much of the few minutes after the Big Bang during which nucleosynthesis could have occurred, the temperature was high enough that the mean energy per particle was greater than the binding energy of weakly bound deuterium; therefore any deuterium that was formed was immediately destroyed. This situation is known as the deuterium bottleneck. The bottleneck delayed formation of any helium-4 until the Universe became cool enough to form deuterium (at about a temperature equivalent to 100 keV). At this point, there was a sudden burst of element formation (first deuterium, which immediately fused to helium). However, very shortly thereafter, at twenty minutes after the Big Bang, the Universe became too cool for any further nuclear fusion and nucleosynthesis to occur. At this point, the elemental abundances were nearly fixed, with the only change as some of the radioactive products of Big Bang nucleosynthesis (such as tritium) decay.[10] The deuterium bottleneck in the formation of helium, together with the lack of stable ways for helium to combine with hydrogen or with itself (there are no stable nuclei with mass numbers of five or eight) meant that an insignificant amount of carbon, or any elements heavier than carbon, formed in the Big Bang. These elements thus required formation in stars. At the same time, the failure of much nucleogenesis during the Big Bang ensured that there would be plenty of hydrogen in the later universe available to form long-lived stars, such as the Sun.

Abundance[edit]

Simplified chart of particle content

Deuterium occurs in trace amounts naturally as deuterium gas, written 2

H

2 or D2, but most of the naturally occurring deuterium atoms in the Universe are bonded with a typical 1

H

atom to form a gas called hydrogen deuteride (HD or 1

H

2

H

).[11] Similarly, natural water contains trace amounts of deuterated molecules, almost all as semiheavy water HDO with only one deuterium atom.

The existence of deuterium on Earth, elsewhere in the Solar System (as confirmed by planetary probes), and in the spectra of stars, is also an important datum in cosmology. Gamma radiation from ordinary nuclear fusion dissociates deuterium into protons and neutrons, and there are no known natural processes other than the Big Bang nucleosynthesis that might have produced deuterium at anything close to its observed natural abundance. Deuterium is produced by the rare cluster decay, and occasional absorption of naturally occurring neutrons by light hydrogen, but these are trivial sources. There is thought to be little deuterium in the interior of the Sun and other stars, as at these temperatures the nuclear fusion reactions that consume deuterium happen much faster than the proton-proton reaction that creates deuterium. However, deuterium persists in the outer solar atmosphere at roughly the same concentration as in Jupiter, and this has probably been unchanged since the origin of the Solar System. The natural abundance of deuterium seems to be a very similar fraction of hydrogen, wherever hydrogen is found, unless there are obvious processes at work that concentrate it.

The existence of deuterium at a low but constant primordial fraction in all hydrogen is another one of the arguments in favor of the Big Bang theory over the Steady State theory of the Universe. The observed ratios of hydrogen to helium to deuterium in the universe are difficult to explain except with a Big Bang model. It is estimated that the abundances of deuterium have not evolved significantly since their production about 13.8 billion years ago.[12] Measurements of Milky Way galactic deuterium from ultraviolet spectral analysis show a ratio of as much as 23 atoms of deuterium per million hydrogen atoms in undisturbed gas clouds, which is only 15% below the WMAP estimated primordial ratio of about 27 atoms per million from the Big Bang. This has been interpreted to mean that less deuterium has been destroyed in star formation in the Milky Way galaxy than expected, or perhaps deuterium has been replenished by a large in-fall of primordial hydrogen from outside the galaxy.[13] In space a few hundred light years from the Sun, deuterium abundance is only 15 atoms per million, but this value is presumably influenced by differential adsorption of deuterium onto carbon dust grains in interstellar space.[14]

The abundance of deuterium in the atmosphere of Jupiter has been directly measured by the Galileo space probe as 26 atoms per million hydrogen atoms. ISO-SWS observations find 22 atoms per million hydrogen atoms in Jupiter.[15] and this abundance is thought to represent close to the primordial Solar System ratio.[5] This is about 17% of the terrestrial deuterium-to-hydrogen ratio of 156 deuterium atoms per million hydrogen atoms.

Cometary bodies such as Comet Hale-Bopp and Halley’s Comet have been measured to contain relatively more deuterium (about 200 atoms D per million hydrogens), ratios which are enriched with respect to the presumed protosolar nebula ratio, probably due to heating, and which are similar to the ratios found in Earth seawater. The recent measurement of deuterium amounts of 161 atoms D per million hydrogen in Comet 103P/Hartley (a former Kuiper belt object), a ratio almost exactly that in Earth’s oceans, emphasizes the theory that Earth’s surface water may be largely comet-derived.[4][5] Most recently the deuterium–protium (D–H) ratio of 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko as measured by Rosetta is about three times that of Earth water, a figure that is high.[6] This has caused renewed interest in suggestions that Earth’s water may be partly of asteroidal origin.

Deuterium has also been observed to be concentrated over the mean solar abundance in other terrestrial planets, in particular Mars and Venus.[16]

Production[edit]

Deuterium is produced for industrial, scientific and military purposes, by starting with ordinary water—a small fraction of which is naturally-occurring heavy water—and then separating out the heavy water by the Girdler sulfide process, distillation, or other methods.[17]

In theory, deuterium for heavy water could be created in a nuclear reactor, but separation from ordinary water is the cheapest bulk production process.

The world’s leading supplier of deuterium was Atomic Energy of Canada Limited until 1997, when the last heavy water plant was shut down. Canada uses heavy water as a neutron moderator for the operation of the CANDU reactor design.

Another major producer of heavy water is India. All but one of India’s atomic energy plants are pressurised heavy water plants, which use natural (i.e., not enriched) uranium. India has eight heavy water plants, of which seven are in operation. Six plants, of which five are in operation, are based on D–H exchange in ammonia gas. The other two plants extract deuterium from natural water in a process that uses hydrogen sulphide gas at high pressure.

While India is self-sufficient in heavy water for its own use, India now also exports reactor-grade heavy water.

Properties[edit]

Data for molecular deuterium[edit]

Formula: D2 or 2

1H

2

- Density: 0.180 kg/m3 at STP (0 °C, 101325 Pa).

- Atomic weight: 2.0141017926 Da.

- Mean abundance in ocean water (from VSMOW) 155.76 ± 0.1 atoms of deuterium per million atoms of all isotopes of hydrogen (a ratio of 1 atom of deuterium per approximately 6420 atoms of all isotopes hydrogen), that is, about 0.015% of the atoms of deuterium in a sample of ocean water with all isotopes hydrogen by number

Data at approximately 18 K for D2 (triple point):

- Density:

- Liquid: 162.4 kg/m3

- Gas: 0.452 kg/m3

- Viscosity: 12.6 μPa·s at 300 K (gas phase)

- Specific heat capacity at constant pressure cp:

- Solid: 2950 J/(kg·K)

- Gas: 5200 J/(kg·K)

Physical properties[edit]

Compared to hydrogen in its natural composition on Earth, pure deuterium (D2) has a higher melting point (18.72 K vs. 13.99 K), a higher boiling point (23.64 K vs. 20.27 K), a higher critical temperature (38.3 K vs. 32.94 K) and a higher critical pressure (1.6496 MPa vs. 1.2858 MPa).[18]

The physical properties of deuterium compounds can exhibit significant kinetic isotope effects and other physical and chemical property differences from the protium analogs. D2O, for example, is more viscous than H2O.[19] Chemically, there are differences in bond energy and length for compounds of heavy hydrogen isotopes compared to protium, which are larger than the isotopic differences in any other element. Bonds involving deuterium and tritium are somewhat stronger than the corresponding bonds in protium, and these differences are enough to cause significant changes in biological reactions. Pharmaceutical firms are interested in the fact that deuterium is harder to remove from carbon than protium.[20]

Deuterium can replace protium in water molecules to form heavy water (D2O), which is about 10.6% denser than normal water (so that ice made from it sinks in ordinary water). Heavy water is slightly toxic in eukaryotic animals, with 25% substitution of the body water causing cell division problems and sterility, and 50% substitution causing death by cytotoxic syndrome (bone marrow failure and gastrointestinal lining failure). Prokaryotic organisms, however, can survive and grow in pure heavy water, though they develop slowly.[21] Despite this toxicity, consumption of heavy water under normal circumstances does not pose a health threat to humans. It is estimated that a 70 kg (154 lb) person might drink 4.8 litres (1.3 US gal) of heavy water without serious consequences.[22] Small doses of heavy water (a few grams in humans, containing an amount of deuterium comparable to that normally present in the body) are routinely used as harmless metabolic tracers in humans and animals.

Quantum properties[edit]

The deuteron has spin +1 («triplet state») and is thus a boson. The NMR frequency of deuterium is significantly different from common light hydrogen. Infrared spectroscopy also easily differentiates many deuterated compounds, due to the large difference in IR absorption frequency seen in the vibration of a chemical bond containing deuterium, versus light hydrogen. The two stable isotopes of hydrogen can also be distinguished by using mass spectrometry.

The triplet deuteron nucleon is barely bound at EB = 2.23 MeV, and none of the higher energy states are bound. The singlet deuteron is a virtual state, with a negative binding energy of ~60 keV. There is no such stable particle, but this virtual particle transiently exists during neutron-proton inelastic scattering, accounting for the unusually large neutron scattering cross-section of the proton.[23]

Nuclear properties (the deuteron)[edit]

Deuteron mass and radius[edit]

The nucleus of deuterium is called a deuteron. It has a mass of 2.013553212745(40) Da (just over 1.875 GeV).[24][25]

The charge radius of the deuteron is 2.12799(74) fm.[26]

Like the proton radius, measurements using muonic deuterium produce a smaller result: 2.12562(78) fm.[27]

Spin and energy[edit]

Deuterium is one of only five stable nuclides with an odd number of protons and an odd number of neutrons. (2

H

, 6

Li

, 10

B

, 14

N

, 180m

Ta

; also, the long-lived radioactive nuclides 40

K

, 50

V

, 138

La

, 176

Lu

occur naturally.) Most odd-odd nuclei are unstable with respect to beta decay, because the decay products are even-even, and are therefore more strongly bound, due to nuclear pairing effects. Deuterium, however, benefits from having its proton and neutron coupled to a spin-1 state, which gives a stronger nuclear attraction; the corresponding spin-1 state does not exist in the two-neutron or two-proton system, due to the Pauli exclusion principle which would require one or the other identical particle with the same spin to have some other different quantum number, such as orbital angular momentum. But orbital angular momentum of either particle gives a lower binding energy for the system, primarily due to increasing distance of the particles in the steep gradient of the nuclear force. In both cases, this causes the diproton and dineutron nucleus to be unstable.

The proton and neutron making up deuterium can be dissociated through neutral current interactions with neutrinos. The cross section for this interaction is comparatively large, and deuterium was successfully used as a neutrino target in the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory experiment.

Diatomic deuterium (D2) has ortho and para nuclear spin isomers like diatomic hydrogen, but with differences in the number and population of spin states and rotational levels, which occur because the deuteron is a boson with nuclear spin equal to one.[28]

Isospin singlet state of the deuteron[edit]

Due to the similarity in mass and nuclear properties between the proton and neutron, they are sometimes considered as two symmetric types of the same object, a nucleon. While only the proton has an electric charge, this is often negligible due to the weakness of the electromagnetic interaction relative to the strong nuclear interaction. The symmetry relating the proton and neutron is known as isospin and denoted I (or sometimes T).

Isospin is an SU(2) symmetry, like ordinary spin, so is completely analogous to it. The proton and neutron, each of which have isospin-1⁄2, form an isospin doublet (analogous to a spin doublet), with a «down» state (↓) being a neutron and an «up» state (↑) being a proton.[citation needed] A pair of nucleons can either be in an antisymmetric state of isospin called singlet, or in a symmetric state called triplet. In terms of the «down» state and «up» state, the singlet is

, which can also be written :

This is a nucleus with one proton and one neutron, i.e. a deuterium nucleus. The triplet is

and thus consists of three types of nuclei, which are supposed to be symmetric: a deuterium nucleus (actually a highly excited state of it), a nucleus with two protons, and a nucleus with two neutrons. These states are not stable.

Approximated wavefunction of the deuteron[edit]

The deuteron wavefunction must be antisymmetric if the isospin representation is used (since a proton and a neutron are not identical particles, the wavefunction

need not be antisymmetric in general). Apart from their isospin, the two nucleons also have spin and spatial distributions of their wavefunction. The latter is symmetric if the deuteron is symmetric under parity (i.e. have an «even» or «positive» parity), and antisymmetric if the deuteron is antisymmetric under parity (i.e. have an «odd» or «negative» parity). The parity is fully determined by the total orbital angular momentum of the two nucleons: if it is even then the parity is even (positive), and if it is odd then the parity is odd (negative).

The deuteron, being an isospin singlet, is antisymmetric under nucleons exchange due to isospin, and therefore must be symmetric under the double exchange of their spin and location. Therefore, it can be in either of the following two different states:

- Symmetric spin and symmetric under parity. In this case, the exchange of the two nucleons will multiply the deuterium wavefunction by (−1) from isospin exchange, (+1) from spin exchange and (+1) from parity (location exchange), for a total of (−1) as needed for antisymmetry.

- Antisymmetric spin and antisymmetric under parity. In this case, the exchange of the two nucleons will multiply the deuterium wavefunction by (−1) from isospin exchange, (−1) from spin exchange and (−1) from parity (location exchange), again for a total of (−1) as needed for antisymmetry.

In the first case the deuteron is a spin triplet, so that its total spin s is 1. It also has an even parity and therefore even orbital angular momentum l ; The lower its orbital angular momentum, the lower its energy. Therefore, the lowest possible energy state has s = 1, l = 0.

In the second case the deuteron is a spin singlet, so that its total spin s is 0. It also has an odd parity and therefore odd orbital angular momentum l. Therefore, the lowest possible energy state has s = 0, l = 1.

Since s = 1 gives a stronger nuclear attraction, the deuterium ground state is in the s = 1, l = 0 state.

The same considerations lead to the possible states of an isospin triplet having s = 0, l = even or s = 1, l = odd. Thus the state of lowest energy has s = 1, l = 1, higher than that of the isospin singlet.

The analysis just given is in fact only approximate, both because isospin is not an exact symmetry, and more importantly because the strong nuclear interaction between the two nucleons is related to angular momentum in spin–orbit interaction that mixes different s and l states. That is, s and l are not constant in time (they do not commute with the Hamiltonian), and over time a state such as s = 1, l = 0 may become a state of s = 1, l = 2. Parity is still constant in time so these do not mix with odd l states (such as s = 0, l = 1). Therefore, the quantum state of the deuterium is a superposition (a linear combination) of the s = 1, l = 0 state and the s = 1, l = 2 state, even though the first component is much bigger. Since the total angular momentum j is also a good quantum number (it is a constant in time), both components must have the same j, and therefore j = 1. This is the total spin of the deuterium nucleus.

To summarize, the deuterium nucleus is antisymmetric in terms of isospin, and has spin 1 and even (+1) parity. The relative angular momentum of its nucleons l is not well defined, and the deuteron is a superposition of mostly l = 0 with some l = 2.

Magnetic and electric multipoles[edit]

In order to find theoretically the deuterium magnetic dipole moment μ, one uses the formula for a nuclear magnetic moment

with

g(l) and g(s) are g-factors of the nucleons.

Since the proton and neutron have different values for g(l) and g(s), one must separate their contributions. Each gets half of the deuterium orbital angular momentum

where subscripts p and n stand for the proton and neutron, and g(l)n = 0.

By using the same identities as here and using the value g(l)p = 1, we arrive at the following result, in units of the nuclear magneton μN

For the s = 1, l = 0 state (j = 1), we obtain

For the s = 1, l = 2 state (j = 1), we obtain

The measured value of the deuterium magnetic dipole moment, is 0.857 μN, which is 97.5% of the 0.879 μN value obtained by simply adding moments of the proton and neutron. This suggests that the state of the deuterium is indeed to a good approximation s = 1, l = 0 state, which occurs with both nucleons spinning in the same direction, but their magnetic moments subtracting because of the neutron’s negative moment.

But the slightly lower experimental number than that which results from simple addition of proton and (negative) neutron moments shows that deuterium is actually a linear combination of mostly s = 1, l = 0 state with a slight admixture of s = 1, l = 2 state.

The electric dipole is zero as usual.

The measured electric quadrupole of the deuterium is 0.2859 e·fm2. While the order of magnitude is reasonable, since the deuterium radius is of order of 1 femtometer (see below) and its electric charge is e, the above model does not suffice for its computation. More specifically, the electric quadrupole does not get a contribution from the l =0 state (which is the dominant one) and does get a contribution from a term mixing the l =0 and the l =2 states, because the electric quadrupole operator does not commute with angular momentum.

The latter contribution is dominant in the absence of a pure l = 0 contribution, but cannot be calculated without knowing the exact spatial form of the nucleons wavefunction inside the deuterium.

Higher magnetic and electric multipole moments cannot be calculated by the above model, for similar reasons.

Applications[edit]

Deuterium has a number of commercial and scientific uses. These include:

Nuclear reactors[edit]

Ionized deuterium in a fusor reactor giving off its characteristic pinkish-red glow

Deuterium is used in heavy water moderated fission reactors, usually as liquid D2O, to slow neutrons without the high neutron absorption of ordinary hydrogen.[29] This is a common commercial use for larger amounts of deuterium.

In research reactors, liquid D2 is used in cold sources to moderate neutrons to very low energies and wavelengths appropriate for scattering experiments.

Experimentally, deuterium is the most common nuclide used in nuclear fusion reactor designs, especially in combination with tritium, because of the large reaction rate (or nuclear cross section) and high energy yield of the D–T reaction. There is an even higher-yield D–3

He

fusion reaction, though the breakeven point of D–3

He

is higher than that of most other fusion reactions; together with the scarcity of 3

He

, this makes it implausible as a practical power source until at least D–T and D–D fusion reactions have been performed on a commercial scale. Commercial nuclear fusion is not yet an accomplished technology.

NMR spectroscopy[edit]

Deuterium is most commonly used in hydrogen nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (proton NMR) in the following way. NMR ordinarily requires compounds of interest to be analyzed as dissolved in solution. Because of deuterium’s nuclear spin properties which differ from the light hydrogen usually present in organic molecules, NMR spectra of hydrogen/protium are highly differentiable from that of deuterium, and in practice deuterium is not «seen» by an NMR instrument tuned for light-hydrogen. Deuterated solvents (including heavy water, but also compounds like deuterated chloroform, CDCl3) are therefore routinely used in NMR spectroscopy, in order to allow only the light-hydrogen spectra of the compound of interest to be measured, without solvent-signal interference.

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy can also be used to obtain information about the deuteron’s environment in isotopically labelled samples (Deuterium NMR). For example, the configuration of hydrocarbon chains in lipid bilayers can be quantified using solid state deuterium NMR with deuterium-labelled lipid molecules.[30]

Deuterium NMR spectra are especially informative in the solid state because of its relatively small quadrupole moment in comparison with those of bigger quadrupolar nuclei such as chlorine-35, for example.

Tracing[edit]

In chemistry, biochemistry and environmental sciences, deuterium is used as a non-radioactive, stable isotopic tracer, for example, in the doubly labeled water test. In chemical reactions and metabolic pathways, deuterium behaves somewhat similarly to ordinary hydrogen (with a few chemical differences, as noted). It can be distinguished from ordinary hydrogen most easily by its mass, using mass spectrometry or infrared spectrometry. Deuterium can be detected by femtosecond infrared spectroscopy, since the mass difference drastically affects the frequency of molecular vibrations; deuterium-carbon bond vibrations are found in spectral regions free of other signals.

Measurements of small variations in the natural abundances of deuterium, along with those of the stable heavy oxygen isotopes 17O and 18O, are of importance in hydrology, to trace the geographic origin of Earth’s waters. The heavy isotopes of hydrogen and oxygen in rainwater (so-called meteoric water) are enriched as a function of the environmental temperature of the region in which the precipitation falls (and thus enrichment is related to mean latitude). The relative enrichment of the heavy isotopes in rainwater (as referenced to mean ocean water), when plotted against temperature falls predictably along a line called the global meteoric water line (GMWL). This plot allows samples of precipitation-originated water to be identified along with general information about the climate in which it originated. Evaporative and other processes in bodies of water, and also ground water processes, also differentially alter the ratios of heavy hydrogen and oxygen isotopes in fresh and salt waters, in characteristic and often regionally distinctive ways.[31] The ratio of concentration of 2H to 1H is usually indicated with a delta as δ2H and the geographic patterns of these values are plotted in maps termed as isoscapes. Stable isotopes are incorporated into plants and animals and an analysis of the ratios in a migrant bird or insect can help suggest a rough guide to their origins.[32][33]

Contrast properties[edit]

Neutron scattering techniques particularly profit from availability of deuterated samples: The H and D cross sections are very distinct and different in sign, which allows contrast variation in such experiments. Further, a nuisance problem of ordinary hydrogen is its large incoherent neutron cross section, which is nil for D. The substitution of deuterium atoms for hydrogen atoms thus reduces scattering noise.

Hydrogen is an important and major component in all materials of organic chemistry and life science, but it barely interacts with X-rays. As hydrogen (and deuterium) interact strongly with neutrons, neutron scattering techniques, together with a modern deuteration facility,[34] fills a niche in many studies of macromolecules in biology and many other areas.

Nuclear weapons[edit]

This is discussed below. It is notable that although most stars, including the Sun, generate energy over most of their lives by fusing hydrogen into heavier elements, such fusion of light hydrogen (protium) has never been successful in the conditions attainable on Earth. Thus, all artificial fusion, including the hydrogen fusion that occurs in so-called hydrogen bombs, requires heavy hydrogen (either tritium or deuterium, or both) in order for the process to work.

Drugs[edit]

A deuterated drug is a small molecule medicinal product in which one or more of the hydrogen atoms contained in the drug molecule have been replaced by deuterium. Because of the kinetic isotope effect, deuterium-containing drugs may have significantly lower rates of metabolism, and hence a longer half-life.[35][36][37] In 2017, deutetrabenazine became the first deuterated drug to receive FDA approval.[38]

Reinforced essential nutrients[edit]

Deuterium can be used to reinforce specific oxidation-vulnerable C-H bonds within essential or conditionally essential nutrients,[39] such as certain amino acids, or polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), making them more resistant to oxidative damage. Deuterated polyunsaturated fatty acids, such as linoleic acid, slow down the chain reaction of lipid peroxidation that damage living cells.[40][41] Deuterated ethyl ester of linoleic acid (RT001), developed by Retrotope, is in a compassionate use trial in infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy and has successfully completed a Phase I/II trial in Friedreich’s ataxia.[42][38]

Thermostabilization[edit]

Live vaccines, such as the oral poliovirus vaccine, can be stabilized by deuterium, either alone or in combination with other stabilizers such as MgCl2.[43]

Slowing circadian oscillations[edit]

Deuterium has been shown to lengthen the period of oscillation of the circadian clock when dosed in rats, hamsters, and Gonyaulax dinoflagellates.[44][45][46][47] In rats, chronic intake of 25% D2O disrupts circadian rhythmicity by lengthening the circadian period of suprachiasmatic nucleus-dependent rhythms in the brain’s hypothalamus.[46] Experiments in hamsters also support the theory that deuterium acts directly on the suprachiasmatic nucleus to lengthen the free-running circadian period.[48]

History[edit]

Suspicion of lighter element isotopes[edit]

The existence of nonradioactive isotopes of lighter elements had been suspected in studies of neon as early as 1913, and proven by mass spectrometry of light elements in 1920. At that time the neutron had not yet been discovered, and the prevailing theory was that isotopes of an element differ by the existence of additional protons in the nucleus accompanied by an equal number of nuclear electrons. In this theory, the deuterium nucleus with mass two and charge one would contain two protons and one nuclear electron. However, it was expected that the element hydrogen with a measured average atomic mass very close to 1 Da, the known mass of the proton, always has a nucleus composed of a single proton (a known particle), and could not contain a second proton. Thus, hydrogen was thought to have no heavy isotopes.

Deuterium detected[edit]

It was first detected spectroscopically in late 1931 by Harold Urey, a chemist at Columbia University. Urey’s collaborator, Ferdinand Brickwedde, distilled five liters of cryogenically produced liquid hydrogen to 1 mL of liquid, using the low-temperature physics laboratory that had recently been established at the National Bureau of Standards in Washington, D.C. (now the National Institute of Standards and Technology). The technique had previously been used to isolate heavy isotopes of neon. The cryogenic boiloff technique concentrated the fraction of the mass-2 isotope of hydrogen to a degree that made its spectroscopic identification unambiguous.[49][50]

Naming of the isotope and Nobel Prize[edit]

Urey created the names protium, deuterium, and tritium in an article published in 1934. The name is based in part on advice from G. N. Lewis who had proposed the name «deutium». The name is derived from the Greek deuteros (‘second’), and the nucleus to be called «deuteron» or «deuton». Isotopes and new elements were traditionally given the name that their discoverer decided. Some British scientists, such as Ernest Rutherford, wanted the isotope to be called «diplogen», from the Greek diploos (‘double’), and the nucleus to be called «diplon».[3][51]

The amount inferred for normal abundance of this heavy isotope of hydrogen was so small (only about 1 atom in 6400 hydrogen atoms in ocean water (156 deuteriums per million hydrogens)) that it had not noticeably affected previous measurements of (average) hydrogen atomic mass. This explained why it hadn’t been experimentally suspected before. Urey was able to concentrate water to show partial enrichment of deuterium. Lewis had prepared the first samples of pure heavy water in 1933. The discovery of deuterium, coming before the discovery of the neutron in 1932, was an experimental shock to theory, but when the neutron was reported, making deuterium’s existence more explainable, deuterium won Urey the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1934. Lewis was embittered by being passed over for this recognition given to his former student.[3]

«Heavy water» experiments in World War II[edit]

Shortly before the war, Hans von Halban and Lew Kowarski moved their research on neutron moderation from France to Britain, smuggling the entire global supply of heavy water (which had been made in Norway) across in twenty-six steel drums.[52][53]

During World War II, Nazi Germany was known to be conducting experiments using heavy water as moderator for a nuclear reactor design. Such experiments were a source of concern because they might allow them to produce plutonium for an atomic bomb. Ultimately it led to the Allied operation called the «Norwegian heavy water sabotage», the purpose of which was to destroy the Vemork deuterium production/enrichment facility in Norway. At the time this was considered important to the potential progress of the war.

After World War II ended, the Allies discovered that Germany was not putting as much serious effort into the program as had been previously thought. The Germans had completed only a small, partly built experimental reactor (which had been hidden away) and had been unable to sustain a chain reaction. By the end of the war, the Germans did not even have a fifth of the amount of heavy water needed to run the reactor,[clarification needed] partially due to the Norwegian heavy water sabotage operation. However, even if the Germans had succeeded in getting a reactor operational (as the U.S. did with Chicago Pile-1 in late 1942), they would still have been at least several years away from the development of an atomic bomb. The engineering process, even with maximal effort and funding, required about two and a half years (from first critical reactor to bomb) in both the U.S. and U.S.S.R., for example.

In thermonuclear weapons[edit]

The «Sausage» device casing of the Ivy Mike H bomb, attached to instrumentation and cryogenic equipment. The 20-ft-tall bomb held a cryogenic Dewar flask with room for 160 kg of liquid deuterium.

The 62-ton Ivy Mike device built by the United States and exploded on 1 November 1952, was the first fully successful «hydrogen bomb» (thermonuclear bomb). In this context, it was the first bomb in which most of the energy released came from nuclear reaction stages that followed the primary nuclear fission stage of the atomic bomb. The Ivy Mike bomb was a factory-like building, rather than a deliverable weapon. At its center, a very large cylindrical, insulated vacuum flask or cryostat, held cryogenic liquid deuterium in a volume of about 1000 liters (160 kilograms in mass, if this volume had been completely filled). Then, a conventional atomic bomb (the «primary») at one end of the bomb was used to create the conditions of extreme temperature and pressure that were needed to set off the thermonuclear reaction.

Within a few years, so-called «dry» hydrogen bombs were developed that did not need cryogenic hydrogen. Released information suggests that all thermonuclear weapons built since then contain chemical compounds of deuterium and lithium in their secondary stages. The material that contains the deuterium is mostly lithium deuteride, with the lithium consisting of the isotope lithium-6. When the lithium-6 is bombarded with fast neutrons from the atomic bomb, tritium (hydrogen-3) is produced, and then the deuterium and the tritium quickly engage in thermonuclear fusion, releasing abundant energy, helium-4, and even more free neutrons. «Pure» fusion weapons such as the Tsar Bomba are believed to be obsolete. In most modern («boosted») thermonuclear weapons, fusion directly provides only a small fraction of the total energy. Fission of a natural uranium U-238 tamper by fast neutrons produced from D-T fusion accounts for a much larger (i.e. boosted) energy release than the fusion reaction itself.

Modern research[edit]

In August 2018, scientists announced the transformation of gaseous deuterium into a liquid metallic form. This may help researchers better understand giant gas planets, such as Jupiter, Saturn and related exoplanets, since such planets are thought to contain a large quantity of liquid metallic hydrogen, which may be responsible for their observed powerful magnetic fields.[54][55]

Antideuterium[edit]

An antideuteron is the antimatter counterpart of the nucleus of deuterium, consisting of an antiproton and an antineutron. The antideuteron was first produced in 1965 at the Proton Synchrotron at CERN[56] and the Alternating Gradient Synchrotron at Brookhaven National Laboratory.[57] A complete atom, with a positron orbiting the nucleus, would be called antideuterium, but as of 2019 antideuterium has not yet been created. The proposed symbol for antideuterium is

D

, that is, D with an overbar.[58]

See also[edit]

- Isotopes of hydrogen

- Nuclear fusion

- Tokamak

- Tritium

- Heavy water

References[edit]

- ^ Hagemann R, Nief G, Roth E (1970). «Absolute isotopic scale for deuterium analysis of natural waters. Absolute D/H ratio for SMOW 1». Tellus. 22 (6): 712–715. doi:10.1111/j.2153-3490.1970.tb00540.x.

- ^ Wang, M.; Audi, G.; Kondev, F. G.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S.; Xu, X. (2017). «The AME2016 atomic mass evaluation (II). Tables, graphs, and references» (PDF). Chinese Physics C. 41 (3): 030003-1–030003-442. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/41/3/030003.

- ^ a b c O’Leary D (February 2012). «The deeds to deuterium». Nature Chemistry. 4 (3): 236. Bibcode:2012NatCh…4..236O. doi:10.1038/nchem.1273. PMID 22354440.

- ^ a b Hartogh P, Lis DC, Bockelée-Morvan D, de Val-Borro M, Biver N, Küppers M, et al. (October 2011). «Ocean-like water in the Jupiter-family comet 103P/Hartley 2». Nature. 478 (7368): 218–220. Bibcode:2011Natur.478..218H. doi:10.1038/nature10519. PMID 21976024. S2CID 3139621.

- ^ a b c Hersant F, Gautier D, Hure J (2001). «A two-dimensional model for the primordial nebula constrained by D/H measurements in the Solar system: Implications for the formation of giant planets». The Astrophysical Journal. 554 (1): 391–407. Bibcode:2001ApJ…554..391H. doi:10.1086/321355. — see fig. 7. for a review of D/H ratios in various astronomical objects

- ^ a b Altwegg K, Balsiger H, Bar-Nun A, Berthelier JJ, Bieler A, Bochsler P, et al. (January 2015). «Cometary science. 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko, a Jupiter family comet with a high D/H ratio» (PDF). Science. 347 (6220): 1261952. Bibcode:2015Sci…347A.387A. doi:10.1126/science.1261952. PMID 25501976. S2CID 206563296.

- ^ «Provisional Recommendations». Nomenclature of Inorganic Chemistry. Chemical Nomenclature and Structure Representation Division. IUPAC. § IR-3.3.2. Archived from the original on 27 October 2006. Retrieved 3 October 2007.

- ^ Hébrard G, Péquignot D, Vidal-Madjar A, Walsh JR, Ferlet R (7 February 2000). «Detection of deuterium Balmer lines in the Orion Nebula». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 354: L79. arXiv:astro-ph/0002141. Bibcode:2000A&A…354L..79H.

- ^ «Water absorption spectrum». London South Bank University (lsbu.ac.uk). London, UK. Archived from the original on 27 July 2017.

- ^ Weiss A. «Equilibrium and change: The physics behind Big Bang nucleosynthesis». Einstein Online. Archived from the original on 8 February 2007. Retrieved 24 February 2007.

- ^ IUPAC Commission on Nomenclature of Inorganic Chemistry (2001). «Names for muonium and hydrogen atoms and their ions» (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 73 (2): 377–380. doi:10.1351/pac200173020377. S2CID 97138983. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 April 2003.

- ^ «Cosmic Detectives». The European Space Agency (ESA). 2 April 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ^ «FUSE Satellite solves the case of the missing deuterium» (Press release). NASA.

- ^ «Graph of deuterium with distance in our galactic neighborhood». FUSE Satellite project. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University. Archived from the original on 5 December 2013.

- See also

Linsky JL, Draine BT, Moos HW, Jenkins EB, Wood BE, Oliveira C, et al. (2006). «What is the Total Deuterium Abundance in the Local Galactic Disk?». The Astrophysical Journal. 647 (2): 1106–1124. arXiv:astro-ph/0608308. Bibcode:2006ApJ…647.1106L. doi:10.1086/505556. S2CID 14461382.

- ^ Lellouch E, Bézard B, Fouchet T, Feuchtgruber H, Encrenaz T, de Graauw T (2001). «The deuterium abundance in Jupiter and Saturn from ISO-SWS observations» (PDF). Astronomy & Astrophysics. 670 (2): 610–622. Bibcode:2001A&A…370..610L. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20010259.

- ^ Hunten DM (1993). «Atmospheric evolution of the terrestrial planets». Science. 259 (5097): 915–920. Bibcode:1993Sci…259..915H. doi:10.1126/science.259.5097.915. ISSN 0036-8075. JSTOR 2880608. S2CID 178360068.

- ^ «Heavy water — Energy Education». energyeducation.ca. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ «Deuterium, 2H». PubChem. compounds. U.S. National Institutes of Health.

- ^ Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- ^ Halford B (4 July 2016). «The deuterium switcheroo». Chemical & Engineering News. American Chemical Society. pp. 32–36.

- ^ Kushner DJ, Baker A, Dunstall TG (February 1999). «Pharmacological uses and perspectives of heavy water and deuterated compounds». Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 77 (2): 79–88. doi:10.1139/cjpp-77-2-79. PMID 10535697.

- ^ Vertes, Attila, ed. (2003). «Physiological effect of heavy water». Elements and isotopes: formation, transformation, distribution. Dordrecht: Kluwer. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-1-4020-1314-0.

- ^ «Neutron-proton scattering» (PDF). mightylib.mit.edu (course notes). Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Fall 2004. 22.101. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- ^ «Deuteron mass in u». Physics.nist.gov. U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ «Deuteron mass energy equivalent in MeV». Physics.nist.gov. U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ «Deuteron RMS charge radius Physics.nist.gov». U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ Pohl R, Nez F, Fernandes LM, Amaro FD, Biraben F, Cardoso JM, et al. (The CREMA Collaboration) (August 2016). «Laser spectroscopy of muonic deuterium». Science. 353 (6300): 669–673. Bibcode:2016Sci…353..669P. doi:10.1126/science.aaf2468. hdl:10316/80061. PMID 27516595. S2CID 206647315.

- ^ Hollas JM (1996). Modern Spectroscopy (3rd ed.). John Wiley and Sons. p. 115. ISBN 0-471-96523-5.

- ^ See neutron cross section#Typical cross sections

- ^ Seelig J (October 1971). «On the flexibility of hydrocarbon chains in lipid bilayers». Journal of the American Chemical Society. 93 (20): 5017–5022. doi:10.1021/ja00749a006. PMID 4332660.

- ^ «Oxygen – Isotopes and Hydrology». SAHRA. Archived from the original on 2 January 2007. Retrieved 10 September 2007.

- ^ West JB (2009). Isoscapes: Understanding movement, pattern, and process on Earth through isotope mapping. Springer.

- ^ Hobson KA, Van Wilgenburg SL, Wassenaar LI, Larson K (2012). «Linking hydrogen (δ2H) isotopes in feathers and precipitation: Sources of variance and consequences for assignment to isoscapes». PLOS ONE. 7 (4): e35137. Bibcode:2012PLoSO…735137H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035137. PMC 3324428. PMID 22509393.

- ^ «Deuteration». nmi3.eu. Integrated Infrastructure Initiative for Neutron Scattering and Muon Spectroscopy (NMI3). Archived from the original on 3 February 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- ^ Sanderson K (March 2009). «Big interest in heavy drugs». Nature. 458 (7236): 269. doi:10.1038/458269a. PMID 19295573. S2CID 4343676.

- ^ Katsnelson A (June 2013). «Heavy drugs draw heavy interest from pharma backers». Nature Medicine. 19 (6): 656. doi:10.1038/nm0613-656. PMID 23744136. S2CID 29789127.

- ^ Gant TG (May 2014). «Using deuterium in drug discovery: Leaving the label in the drug». Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 57 (9): 3595–3611. doi:10.1021/jm4007998. PMID 24294889.

- ^ a b Schmidt C (June 2017). «First deuterated drug approved». Nature Biotechnology. 35 (6): 493–494. doi:10.1038/nbt0617-493. PMID 28591114. S2CID 205269152.

- ^ Demidov VV (September 2007). «Heavy isotopes to avert ageing?». Trends in Biotechnology. 25 (9): 371–375. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.07.007. PMID 17681625.

- ^ Halliwell, Barry; Gutteridge, John M.C. (2015). Free Radical Biology and Medicine (5th ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198717485.

- ^ Hill S, Lamberson CR, Xu L, To R, Tsui HS, Shmanai VV, et al. (August 2012). «Small amounts of isotope-reinforced polyunsaturated fatty acids suppress lipid autoxidation». Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 53 (4): 893–906. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.06.004. PMC 3437768. PMID 22705367.

- ^ «A Randomized, Double-blind, Controlled Study to Assess the Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacokinetics of RT001 in Patients with Friedreich’s Ataxia». 24 November 2020.

- ^ Wu R, Georgescu MM, Delpeyroux F, Guillot S, Balanant J, Simpson K, Crainic R (August 1995). «Thermostabilization of live virus vaccines by heavy water (D2O)». Vaccine. 13 (12): 1058–1063. doi:10.1016/0264-410X(95)00068-C. PMID 7491812.

- ^ Lesauter J, Silver R (September 1993). «Heavy water lengthens the period of free-running rhythms in lesioned hamsters bearing SCN grafts». Physiology & Behavior. 54 (3): 599–604. doi:10.1016/0031-9384(93)90255-E. ISSN 0031-9384. PMID 8415956. S2CID 32466816.

- ^ McDaniel M, Sulzman FM, Hastings JW (November 1974). «Heavy water slows the Gonyaulax clock: a test of the hypothesis that D2O affects circadian oscillations by diminishing the apparent temperature». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 71 (11): 4389–4391. Bibcode:1974PNAS…71.4389M. doi:10.1073/pnas.71.11.4389. PMC 433889. PMID 4530989.

- ^ a b Petersen CC, Mistlberger RE (August 2017). «Interval timing is preserved despite circadian desynchrony in rats: Constant light and heavy water studies». Journal of Biological Rhythms. 32 (4): 295–308. doi:10.1177/0748730417716231. PMID 28651478. S2CID 4633617.

- ^ Richter CP (March 1977). «Heavy water as a tool for study of the forces that control length of period of the 24-hour clock of the hamster». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 74 (3): 1295–1299. Bibcode:1977PNAS…74.1295R. doi:10.1073/pnas.74.3.1295. PMC 430671. PMID 265574.

- ^ Lesauter J, Silver R (September 1993). «Heavy water lengthens the period of free-running rhythms in lesioned hamsters bearing SCN grafts». Physiology & Behavior. 54 (3): 599–604. doi:10.1016/0031-9384(93)90255-E. PMID 8415956. S2CID 32466816.

- ^ Brickwedde FG (1982). «Harold Urey and the discovery of deuterium». Physics Today. Vol. 35, no. 9. p. 34. Bibcode:1982PhT….35i..34B. doi:10.1063/1.2915259.

- ^ Urey H, Brickwedde F, Murphy G (1932). «A hydrogen isotope of mass 2». Physical Review. 39 (1): 164–165. Bibcode:1932PhRv…39..164U. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.39.164.

- ^ «Deuterium v. Diplogen». Science. Time. 19 February 1934. Archived from the original on 15 September 2009.

- ^ Sherriff L (1 June 2007). «Royal Society unearths top secret nuclear research». The Register. Situation Publishing Ltd. Retrieved 3 June 2007.

- ^ The battle for heavy water: Three physicists’ heroic exploits. CERN Bulletin (Report). European Organization for Nuclear Research. 25 March 2002. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ^ Chang K (16 August 2018). «Settling arguments about hydrogen with 168 giant lasers». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- ^ «Under pressure, hydrogen offers a reflection of giant planet interiors» (Press release). Carnegie Institution for Science. 15 August 2018. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ^ Massam T, Muller T, Righini B, Schneegans M, Zichichi A (1965). «Experimental observation of antideuteron production». Il Nuovo Cimento. 39 (1): 10–14. Bibcode:1965NCimS..39…10M. doi:10.1007/BF02814251. S2CID 122952224.

- ^ Dorfan DE, Eades J, Lederman LM, Lee W, Ting CC (June 1965). «Observation of antideuterons». Physical Review Letters. 14 (24): 1003–1006. Bibcode:1965PhRvL..14.1003D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.14.1003.

- ^ Chardonnet P, Orloff J, Salati P (1997). «The production of anti-matter in our galaxy». Physics Letters B. 409 (1–4): 313–320. arXiv:astro-ph/9705110. Bibcode:1997PhLB..409..313C. doi:10.1016/S0370-2693(97)00870-8. S2CID 118919611.

External links[edit]

Look up deuterium in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- «Nuclear Data Center». KAERI.

- «Annotated bibliography for deuterium». ALSOS: The Digital Library for Nuclear Issues. Lexington, VA: Washington and Lee University. Archived from the original on 5 May 2010. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- Mullins, Justin (27 April 2005). «Desktop nuclear fusion demonstrated». New Scientist.

- Lloyd, Robin (21 August 2006). «Missing gas found in Milky Way». Space.com.

![{displaystyle mu ={frac {1}{4(j+1)}}left[({g^{(s)}}_{p}+{g^{(s)}}_{n}){big (}j(j+1)-l(l+1)+s(s+1){big )}+{big (}j(j+1)+l(l+1)-s(s+1){big )}right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a3c23357e4baf596b679ef024306fab09a5396a8)