| Regular icosahedron | |

|---|---|

(Click here for rotating model) |

|

| Type | Platonic solid |

| Elements | F = 20, E = 30 V = 12 (χ = 2) |

| Faces by sides | 20{3} |

| Conway notation | I sT |

| Schläfli symbols | {3,5} |

| s{3,4} sr{3,3} or

|

|

| Face configuration | V5.5.5 |

| Wythoff symbol | 5 | 2 3 |

| Coxeter diagram | |

| Symmetry | Ih, H3, [5,3], (*532) |

| Rotation group | I, [5,3]+, (532) |

| References | U22, C25, W4 |

| Properties | regular, convexdeltahedron |

| Dihedral angle | 138.189685° = arccos(−√5⁄3) |

3.3.3.3.3 (Vertex figure) |

Regular dodecahedron (dual polyhedron) |

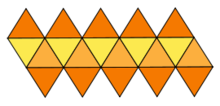

Net |

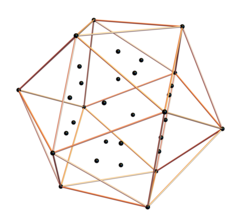

3D model of a regular icosahedron

In geometry, a regular icosahedron ( or [1]) is a convex polyhedron with 20 faces, 30 edges and 12 vertices. It is one of the five Platonic solids, and the one with the most faces.

It has five equilateral triangular faces meeting at each vertex. It is represented by its Schläfli symbol {3,5}, or sometimes by its vertex figure as 3.3.3.3.3 or 35. It is the dual of the regular dodecahedron, which is represented by {5,3}, having three pentagonal faces around each vertex. In most contexts, the unqualified use of the word «icosahedron» refers specifically to this figure.

A regular icosahedron is a strictly convex deltahedron and a gyroelongated pentagonal bipyramid and a biaugmented pentagonal antiprism in any of six orientations.

The name comes from Greek εἴκοσι (eíkosi) ‘twenty’, and ἕδρα (hédra) ‘seat’. The plural can be either «icosahedrons» or «icosahedra» ().

Dimensions[edit]

Net folding into icosahedron

If the edge length of a regular icosahedron is

and the radius of an inscribed sphere (tangent to each of the icosahedron’s faces) is

while the midradius, which touches the middle of each edge, is

where

Area and volume[edit]

The surface area

The latter is F = 20 times the volume of a general tetrahedron with apex at the center of the

inscribed sphere, where the volume of the tetrahedron is one third times the base area

The volume filling factor of the circumscribed sphere is:

compared to 66.49% for a dodecahedron. A sphere inscribed in an icosahedron will enclose 89.635% of its volume, compared to only 75.47% for a dodecahedron.

The midsphere of an icosahedron will have a volume 1.01664 times the volume of the icosahedron, which is by far the closest similarity in volume of any platonic solid with its midsphere. This arguably makes the icosahedron the «roundest» of the platonic solids.

Cartesian coordinates[edit]

Icosahedron vertices form three orthogonal golden rectangles

The vertices of an icosahedron centered at the origin with an edge length of 2 and a circumradius of

where

The vertices of the icosahedron form five sets of three concentric, mutually orthogonal golden rectangles, whose edges form Borromean rings.

If the original icosahedron has edge length 1, its dual dodecahedron has edge length

Model of an icosahedron made with metallic spheres and magnetic connectors

The 12 edges of a regular octahedron can be subdivided in the golden ratio so that the resulting vertices define a regular icosahedron. This is done by first placing vectors along the octahedron’s edges such that each face is bounded by a cycle, then similarly subdividing each edge into the golden mean along the direction of its vector. The five octahedra defining any given icosahedron form a regular polyhedral compound, while the two icosahedra that can be defined in this way from any given octahedron form a uniform polyhedron compound.

The vertices of an icosahedron centred at the origin with an edge length of

Spherical coordinates[edit]

The locations of the vertices of a regular icosahedron can be described using spherical coordinates, for instance as latitude and longitude. If two vertices are taken to be at the north and south poles (latitude ±90°), then the other ten vertices are at latitude ± arctan 1/2 = ±26.57°. These ten vertices are at evenly spaced longitudes (36° apart), alternating between north and south latitudes.

This scheme takes advantage of the fact that the regular icosahedron is a pentagonal gyroelongated bipyramid, with D5d dihedral symmetry—that is, it is formed of two congruent pentagonal pyramids joined by a pentagonal antiprism.

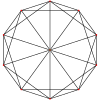

Orthogonal projections[edit]

The icosahedron has three special orthogonal projections, centered on a face, an edge and a vertex:

| Centered by | Face | Edge | Vertex |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coxeter plane | A2 | A3 | H3 |

| Graph |

|

|

|

| Projective symmetry |

[6] | [2] | [10] |

| Graph |  Face normal |

Edge normal |

Vertex normal |

As a configuration[edit]

This configuration matrix represents the icosahedron. The rows and columns correspond to vertices, edges, and faces. The diagonal numbers say how many of each element occur in the whole icosahedron. The nondiagonal numbers say how many of the column’s element occur in or at the row’s element.[3][4]

Here is the configuration expanded with k-face elements and k-figures. The diagonal element counts are the ratio of the full Coxeter group H3, order 120, divided by the order of the subgroup with mirror removal.

| H3 | k-face | fk | f0 | f1 | f2 | k-fig | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A2 | ( ) | f0 | 12 | 5 | 5 | {5} | H3/H2 = 120/10 = 12 | |

| A1A1 | { } | f1 | 2 | 30 | 2 | { } | H3/A1A1 = 120/4 = 30 | |

| H2 | {3} | f2 | 3 | 3 | 20 | ( ) | H3/A2 = 120/6 = 20 |

Spherical tiling[edit]

The icosahedron can also be represented as a spherical tiling, and projected onto the plane via a stereographic projection. This projection is conformal, preserving angles but not areas or lengths. Straight lines on the sphere are projected as circular arcs on the plane.

|

|

| Orthographic projection | Stereographic projection |

|---|

Other facts[edit]

- An icosahedron has 43,380 distinct nets.[5]

- To color the icosahedron, such that no two adjacent faces have the same color, requires at least 3 colors.[a]

- A problem dating back to the ancient Greeks is to determine which of two shapes has larger volume, an icosahedron inscribed in a sphere, or a dodecahedron inscribed in the same sphere. The problem was solved by Hero, Pappus, and Fibonacci, among others.[6] Apollonius of Perga discovered the curious result that the ratio of volumes of these two shapes is the same as the ratio of their surface areas.[7] Both volumes have formulas involving the golden ratio, but taken to different powers.[8] As it turns out, the icosahedron occupies less of the sphere’s volume (60.54%) than the dodecahedron (66.49%).[9]

- Icosahedral angle — the angle between the closest vertices of the icosahedron, relative to the center of the body of the icosahedron (3D), is equal to the diagonal angle of a double and / or half square (≈ 63.434949°)

Construction by a system of equiangular lines[edit]

The following construction of the icosahedron avoids tedious computations in the number field ![{displaystyle mathbb {Q} [{sqrt {5}}]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5691f5e84ebcf23acbd458f90f57c0945549be8c)

The existence of the icosahedron amounts to the existence of six equiangular lines in

In order to construct such an equiangular system, we start with this 6 × 6 square matrix:

A straightforward computation yields

The matrix

A second straightforward construction of the icosahedron uses representation theory of the alternating group

Symmetry[edit]

Full Icosahedral symmetry has 15 mirror planes (seen as cyan great circles on this sphere) meeting at order

The rotational symmetry group of the regular icosahedron is isomorphic to the alternating group on five letters. This non-abelian simple group is the only non-trivial normal subgroup of the symmetric group on five letters. Since the Galois group of the general quintic equation is isomorphic to the symmetric group on five letters, and this normal subgroup is simple and non-abelian, the general quintic equation does not have a solution in radicals. The proof of the Abel–Ruffini theorem uses this simple fact, and Felix Klein wrote a book that made use of the theory of icosahedral symmetries to derive an analytical solution to the general quintic equation, (Klein 1884). See icosahedral symmetry: related geometries for further history, and related symmetries on seven and eleven letters.

The full symmetry group of the icosahedron (including reflections) is known as the full icosahedral group, and is isomorphic to the product of the rotational symmetry group and the group

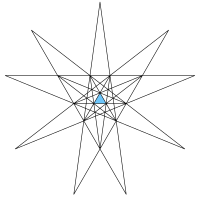

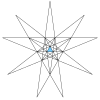

Stellations[edit]

The icosahedron has a large number of stellations. According to specific rules defined in the book The Fifty-Nine Icosahedra,[10] 59 stellations were identified for the regular icosahedron. The first form is the icosahedron itself. One is a regular Kepler–Poinsot polyhedron. Three are regular compound polyhedra.

The faces of the icosahedron extended outwards as planes intersect, defining regions in space as shown by this stellation diagram of the intersections in a single plane. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

Facetings[edit]

The small stellated dodecahedron, great dodecahedron, and great icosahedron are three facetings of the regular icosahedron. They share the same vertex arrangement. They all have 30 edges. The regular icosahedron and great dodecahedron share the same edge arrangement but differ in faces (triangles vs pentagons), as do the small stellated dodecahedron and great icosahedron (pentagrams vs triangles).

| Convex | Regular stars | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| icosahedron | great dodecahedron | small stellated dodecahedron | great icosahedron |

|

|

|

|

Geometric relations[edit]

Inscribed in other Platonic solids[edit]

The regular icosahedron is the dual polyhedron of the regular dodecahedron. An icosahedron can be inscribed in a dodecahedron by placing its vertices at the face centers of the dodecahedron, and vice versa.

An icosahedron can be inscribed in an octahedron by placing its 12 vertices on the 12 edges of the octahedron such that they divide each edge into its two golden sections. Because the golden sections are unequal, there are five different ways to do this consistently, so five disjoint icosahedra can be inscribed in each octahedron.[11]

An icosahedron of edge length

Relations to the 600-cell and other 4-polytopes[edit]

The icosahedron is the dimensional analogue of the 600-cell, a regular 4-dimensional polytope. The 600-cell has icosahedral cross sections of two sizes, and each of its 120 vertices is an icosahedral pyramid; the icosahedron is the vertex figure of the 600-cell.

The unit-radius 600-cell has tetrahedral cells of edge length

A semiregular 4-polytope, the snub 24-cell, has icosahedral cells.

Relations to other uniform polytopes[edit]

The icosahedron is unique among the Platonic solids in possessing a dihedral angle not less than 120°. Its dihedral angle is approximately 138.19°. Thus, just as hexagons have angles not less than 120° and cannot be used as the faces of a convex regular polyhedron because such a construction would not meet the requirement that at least three faces meet at a vertex and leave a positive defect for folding in three dimensions, icosahedra cannot be used as the cells of a convex regular polychoron because, similarly, at least three cells must meet at an edge and leave a positive defect for folding in four dimensions (in general for a convex polytope in n dimensions, at least three facets must meet at a peak and leave a positive defect for folding in n-space). However, when combined with suitable cells having smaller dihedral angles, icosahedra can be used as cells in semi-regular polychora (for example the snub 24-cell), just as hexagons can be used as faces in semi-regular polyhedra (for example the truncated icosahedron). Finally, non-convex polytopes do not carry the same strict requirements as convex polytopes, and icosahedra are indeed the cells of the icosahedral 120-cell, one of the ten non-convex regular polychora.

There are distortions of the icosahedron that, while no longer regular, are nevertheless vertex-uniform. These are invariant under the same rotations as the tetrahedron, and are somewhat analogous to the snub cube and snub dodecahedron, including some forms which are chiral and some with Th-symmetry, i.e. have different planes of symmetry from the tetrahedron.

An icosahedron can also be called a gyroelongated pentagonal bipyramid. It can be decomposed into a gyroelongated pentagonal pyramid and a pentagonal pyramid or into a pentagonal antiprism and two equal pentagonal pyramids.

Relation to the 6-cube and rhombic triacontahedron[edit]

The icosahedron can be projected to 3D from the 6D 6-demicube using the same basis vectors that form the hull of the Rhombic triacontahedron from the 6-cube. Shown here including the inner 20 vertices which are not connected by the 30 outer hull edges of 6D norm length

The 3D projection basis vectors [u,v,w] used are:

Symmetries[edit]

There are 3 uniform colorings of the icosahedron. These colorings can be represented as 11213, 11212, 11111, naming the 5 triangular faces around each vertex by their color.

The icosahedron can be considered a snub tetrahedron, as snubification of a regular tetrahedron gives a regular icosahedron having chiral tetrahedral symmetry. It can also be constructed as an alternated truncated octahedron, having pyritohedral symmetry. The pyritohedral symmetry version is sometimes called a pseudoicosahedron, and is dual to the pyritohedron.

| Regular | Uniform | 2-uniform | 3-uniform | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Regular icosahedron |

Snub octahedron |

Snub tetratetrahedron |

Gyroelongated pentagonal bipyramid |

Triangular gyrobianticupola |

Snub triangular antiprism[13] |

Snub square bipyramid |

| Image |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Face coloring |

(11111) | (11212) | (11213) | (11122) (22222) |

(12332) (23333) |

(11213) (11212) |

(11424) (22434) (33414) |

| Coxeter diagram |

|||||||

| Schläfli symbol |

{3,5} | s{3,4} | sr{3,3} | () || {n} || r{n} || () | ss{2,6} | sdt{2,4} | |

| Conway | I | HtO | sT | k5A5 | sY3 = HtA3 | HtdP4 | |

| Symmetry | Ih [5,3] (*532) |

Th [3+,4] (3*2) |

T [3,3]+ (332) |

D5d [2+,10] (2*5) |

D3d [2+,6] (2*3) |

D3 [3,2]+ (322) |

D2h [2,2] (*222) |

| Symmetry order |

120 | 24 | 12 | 20 | 12 | 6 | 8 |

Uses and natural forms[edit]

Biology[edit]

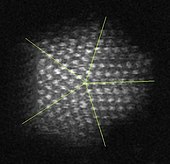

Many viruses, e.g. herpes virus, have icosahedral shells.[14] Viral structures are built of repeated identical protein subunits known as capsomeres, and the icosahedron is the easiest shape to assemble using these subunits. A regular polyhedron is used because it can be built from a single basic unit protein used over and over again; this saves space in the viral genome.

Various bacterial organelles with an icosahedral shape were also found.[15] The icosahedral shell encapsulating enzymes and labile intermediates are built of different types of proteins with BMC domains.

In 1904, Ernst Haeckel described a number of species of Radiolaria, including Circogonia icosahedra, whose skeleton is shaped like a regular icosahedron. A copy of Haeckel’s illustration for this radiolarian appears in the article on regular polyhedra.

Chemistry[edit]

The closo-carboranes are chemical compounds with shape very close to icosahedron. Icosahedral twinning also occurs in crystals, especially nanoparticles.

Many borides and allotropes of boron contain boron B12 icosahedron as a basic structure unit.

Toys and games[edit]

Icosahedral dice with twenty sides have been used since ancient times.[16]

In several roleplaying games, such as Dungeons & Dragons, the twenty-sided die (d20 for short) is commonly used in determining success or failure of an action. This die is in the form of a regular icosahedron. It may be numbered from «0» to «9» twice (in which form it usually serves as a ten-sided die, or d10), but most modern versions are labeled from «1» to «20».

An icosahedron is used in the board game Scattergories to choose a letter of the alphabet. Six letters are omitted (Q, U, V, X, Y, and Z).

In the Nintendo 64 game Kirby 64: The Crystal Shards, the boss Miracle Matter is a regular icosahedron.

Inside a Magic 8-Ball, various answers to yes–no questions are inscribed on a regular icosahedron.

Tensegrity[edit]

The octahedron has been widely studied in the field of tensegrity. Due to its spherical symmetry and high strength to mass ratio, the shape became a good candidate for deployable tensegrity space structures such as NASA’s SuperBALL.[17] The robot is composed of rods, cables and actuators of different scales and is currently in development between NASA Ames Research Center’s Intelligent Robotics Group and the Dynamic Tensegrity Robotics Lab (DTRL). Its undeployed configuration is highly compact, hence being ideal for fitting within the space-constraints of rocket fairings.[18]

The Icosahedron in tensegrity is composed of six struts and twenty-four cables that connect twelve nodes. One self-stress state is present within the combination achieved through the use of cellular morphogenesis.[19]

Others[edit]

R. Buckminster Fuller and Japanese cartographer Shoji Sadao[20] designed a world map in the form of an unfolded icosahedron, called the Fuller projection, whose maximum distortion is only 2%.

The American electronic music duo ODESZA use a regular icosahedron as their logo.

Icosahedral graph[edit]

| Regular icosahedron graph | |

|---|---|

3-fold symmetry |

|

| Vertices | 12 |

| Edges | 30 |

| Radius | 3 |

| Diameter | 3 |

| Girth | 3 |

| Automorphisms | 120 (A5 × Z2) |

| Chromatic number | 4 |

| Properties | Hamiltonian, regular, symmetric, distance-regular, distance-transitive, 3-vertex-connected, planar graph |

| Table of graphs and parameters |

The skeleton of the icosahedron (the vertices and edges) forms a graph. It is one of 5 Platonic graphs, each a skeleton of its Platonic solid.

The high degree of symmetry of the polygon is replicated in the properties of this graph, which is distance-transitive and symmetric. The automorphism group has order 120. The vertices can be colored with 4 colors, the edges with 5 colors, and the diameter is 3.[21]

The icosahedral graph is Hamiltonian: there is a cycle containing all the vertices. It is also a planar graph.

|

Diminished regular icosahedra[edit]

There are 4 related Johnson solids, including pentagonal faces with a subset of the 12 vertices. The similar dissected regular icosahedron has 2 adjacent vertices diminished, leaving two trapezoidal faces, and a bifastigium has 2 opposite sets of vertices removed and 4 trapezoidal faces. The pentagonal antiprism is formed by removing two opposite vertices.

| Form | J2 | Bifastigium | J63 | J62 | Dissected icosahedron |

s{2,10} | J11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vertices | 6 of 12 | 8 of 12 | 9 of 12 | 10 of 12 | 11 of 12 | ||

| Symmetry | C5v, [5], (*55) order 10 |

D2h, [2,2], *222 order 8 |

C3v, [3], (*33) order 6 |

C2v, [2], (*22) order 4 |

D5d, [2+,10], (2*5) order 20 |

C5v, [5], (*55) order 10 |

|

| Image |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Related polyhedra and polytopes[edit]

The icosahedron can be transformed by a truncation sequence into its dual, the dodecahedron:

| Family of uniform icosahedral polyhedra | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [5,3], (*532) | [5,3]+, (532) | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| {5,3} | t{5,3} | r{5,3} | t{3,5} | {3,5} | rr{5,3} | tr{5,3} | sr{5,3} |

| Duals to uniform polyhedra | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| V5.5.5 | V3.10.10 | V3.5.3.5 | V5.6.6 | V3.3.3.3.3 | V3.4.5.4 | V4.6.10 | V3.3.3.3.5 |

As a snub tetrahedron, and alternation of a truncated octahedron it also exists in the tetrahedral and octahedral symmetry families:

| Family of uniform tetrahedral polyhedra | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [3,3], (*332) | [3,3]+, (332) | ||||||

|

|

|

|

||||

| {3,3} | t{3,3} | r{3,3} | t{3,3} | {3,3} | rr{3,3} | tr{3,3} | sr{3,3} |

| Duals to uniform polyhedra | |||||||

|

|

|

|

||||

| V3.3.3 | V3.6.6 | V3.3.3.3 | V3.6.6 | V3.3.3 | V3.4.3.4 | V4.6.6 | V3.3.3.3.3 |

| Uniform octahedral polyhedra | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [4,3], (*432) | [4,3]+ (432) |

[1+,4,3] = [3,3] (*332) |

[3+,4] (3*2) |

|||||||

| {4,3} | t{4,3} | r{4,3} r{31,1} |

t{3,4} t{31,1} |

{3,4} {31,1} |

rr{4,3} s2{3,4} |

tr{4,3} | sr{4,3} | h{4,3} {3,3} |

h2{4,3} t{3,3} |

s{3,4} s{31,1} |

= |

= |

= |

||||||||

| Duals to uniform polyhedra | ||||||||||

| V43 | V3.82 | V(3.4)2 | V4.62 | V34 | V3.43 | V4.6.8 | V34.4 | V33 | V3.62 | V35 |

This polyhedron is topologically related as a part of sequence of regular polyhedra with Schläfli symbols {3,n}, continuing into the hyperbolic plane.

*n32 symmetry mutation of regular tilings: {3,n}

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spherical | Euclid. | Compact hyper. | Paraco. | Noncompact hyperbolic | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3.3 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 3∞ | 312i | 39i | 36i | 33i |

The regular icosahedron, seen as a snub tetrahedron, is a member of a sequence of snubbed polyhedra and tilings with vertex figure (3.3.3.3.n) and Coxeter–Dynkin diagram . These figures and their duals have (n32) rotational symmetry, being in the Euclidean plane for

n32 symmetry mutations of snub tilings: 3.3.3.3.n

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry n32 |

Spherical | Euclidean | Compact hyperbolic | Paracomp. | ||||

| 232 | 332 | 432 | 532 | 632 | 732 | 832 | ∞32 | |

| Snub figures |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Config. | 3.3.3.3.2 | 3.3.3.3.3 | 3.3.3.3.4 | 3.3.3.3.5 | 3.3.3.3.6 | 3.3.3.3.7 | 3.3.3.3.8 | 3.3.3.3.∞ |

| Gyro figures |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Config. | V3.3.3.3.2 | V3.3.3.3.3 | V3.3.3.3.4 | V3.3.3.3.5 | V3.3.3.3.6 | V3.3.3.3.7 | V3.3.3.3.8 | V3.3.3.3.∞ |

| Spherical | Hyperbolic tilings

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

{2,5} |

{3,5} |

{4,5} |

{5,5} |

{6,5} |

{7,5} |

{8,5} |

… |  {∞,5} |

The icosahedron can tessellate hyperbolic space in the order-3 icosahedral honeycomb, with 3 icosahedra around each edge, 12 icosahedra around each vertex, with Schläfli symbol {3,5,3}. It is one of four regular tessellations in the hyperbolic 3-space.

It is shown here as an edge framework in a Poincaré disk model, with one icosahedron visible in the center.

See also[edit]

- Great icosahedron

- Geodesic grids use an iteratively bisected icosahedron to generate grids on a sphere

- Icosahedral twins

- Infinite skew polyhedron

- Jessen’s icosahedron

- Regular polyhedron

- Truncated icosahedron

Notes[edit]

- ^ This is true for all convex polyhedra with triangular faces except for the tetrahedron, by applying Brooks’ theorem to the dual graph of the polyhedron.

- ^ Reciprocally, the edge length of a cube inscribed in a dodecahedron is in the golden ratio to the dodecahedron’s edge length. The cube’s edges lie in pentagonal face planes of the dodecahedron as regular pentagon diagonals, which are always in the golden ratio to the regular pentagon’s edge. So when a cube is inscribed in a dodecahedron and an icosahedron is inscribed in the cube, the dodecahedron and icosahedron (which do not share any vertices) have the same edge length.

Citations[edit]

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2003) [1917], Peter Roach; James Hartmann; Jane Setter (eds.), English Pronouncing Dictionary, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 3-12-539683-2

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Icosahedral group». MathWorld.

- ^ Coxeter, Regular Polytopes, sec 1.8 Configurations

- ^ Coxeter, Complex Regular Polytopes, p.117

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Regular Icosahedron». MathWorld.

- ^ Herz-Fischler, Roger (2013), A Mathematical History of the Golden Number, Courier Dover Publications, pp. 138–140, ISBN 9780486152325.

- ^ Simmons, George F. (2007), Calculus Gems: Brief Lives and Memorable Mathematics, Mathematical Association of America, p. 50, ISBN 9780883855614.

- ^ Sutton, Daud (2002), Platonic & Archimedean Solids, Wooden Books, Bloomsbury Publishing USA, p. 55, ISBN 9780802713865.

- ^ Numerical values for the volumes of the inscribed Platonic solids may be found in Buker, W. E.; Eggleton, R. B. (1969), «The Platonic Solids (Solution to problem E2053)», American Mathematical Monthly, 76 (2): 192, doi:10.2307/2317282, JSTOR 2317282.

- ^ Coxeter et al. 1938.

- ^ Coxeter et al. 1938, p. 4; «Just as a tetrahedron can be inscribed in a cube, so a cube can be inscribed in a dodecahedron. By reciprocation, this leads to an octahedron circumscribed about an icosahedron. In fact, each of the twelve vertices of the icosahedron divides an edge of the octahedron according to the «golden section». Given the icosahedron, the circumscribed octahedron can be chosen in five ways, giving a compound of five octahedra, which comes under our definition of stellated icosahedron. (The reciprocal compound, of five cubes whose vertices belong to a dodecahedron, is a stellated triacontahedron.) Another stellated icosahedron can at once be deduced, by stellating each octahedron into a stella octangula, thus forming a compound of ten tetrahedra. Further, we can choose one tetrahedron from each stella octangula, so as to derive a compound of five tetrahedra, which still has all the rotation symmetry of the icosahedron (i.e. the icosahedral group), although it has lost the reflections. By reflecting this figure in any plane of symmetry of the icosahedron, we obtain the complementary set of five tetrahedra. These two sets of five tetrahedra are enantiomorphous, i.e. not directly congruent, but related like a pair of shoes. [Such] a figure which possesses no plane of symmetry (so that it is enantiomorphous to its mirror-image) is said to be chiral.»

- ^ Borovik 2006, pp. 8–9, §5. How to draw an icosahedron on a blackboard.

- ^ Snub Anti-Prisms

- ^ C. Michael Hogan. 2010. Virus. Encyclopedia of Earth. National Council for Science and the Environment. eds. S. Draggan and C. Cleveland

- ^ Bobik, T.A. (2007), «Bacterial Microcompartments», Microbe, Am. Soc. Microbiol., 2: 25–31, archived from the original on 2013-07-29

- ^ Cromwell, Peter R. «Polyhedra» (1997) Page 327.

- ^ Sabelhaus, Andrew P.; Bruce, Jonathan; Caluwaerts, Ken; Chen, Yangxin; Lu, Dizhou; Liu, Yuejia; Agogino, Adrian K.; SunSpiral, Vytas; Agogino, Alice M. (2014-07-15). «Hardware Design and Testing of SUPERball, A Modular Tensegrity Robot».

- ^ «NASA’s Super Ball Bot Could Be the Best Design for Planetary Exploration». IEEE Spectrum. 2015-03-02. Retrieved 2022-12-22.

- ^ Aloui, Omar; Flores, Jessica; Orden, David; Rhode-Barbarigos, Landolf (2019-04-01). «Cellular morphogenesis of three-dimensional tensegrity structures». Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering. 346: 85–108. arXiv:1902.09953. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2018.10.048. ISSN 0045-7825. S2CID 67856423.

- ^ «Fuller and Sadao: Partners in Design». September 19, 2006. Archived from the original on August 16, 2010. Retrieved 2010-01-26.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Icosahedral Graph». MathWorld.

References[edit]

- Klein, Felix (1888), Lectures on the ikosahedron and the solution of equations of the fifth degree, ISBN 978-0-486-49528-6, Dover edition

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link), translated from Klein, Felix (1884). Vorlesungen über das Ikosaeder und die Auflösung der Gleichungen vom fünften Grade. Teubner. - Coxeter, H.S.M.; du Val, Patrick; Flather, H.T.; Petrie, J.F. (1938). The Fifty-Nine Icosahedra. Vol. 6. University of Toronto Studies (Mathematical Series).

- Borovik, Alexandre (2006). «Coxeter Theory: The Cognitive Aspects». In Davis, Chandler; Ellers, Erich (eds.). The Coxeter Legacy. Providence, Rhode Island: American Mathematical Society. pp. 17–43. ISBN 978-0821837221.

External links[edit]

Look up icosahedron in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Klitzing, Richard. «3D convex uniform polyhedra x3o5o – ike».

- Hartley, Michael. «Dr Mike’s Math Games for Kids».

- K.J.M. MacLean, A Geometric Analysis of the Five Platonic Solids and Other Semi-Regular Polyhedra

- Virtual Reality Polyhedra The Encyclopedia of Polyhedra

- Tulane.edu A discussion of viral structure and the icosahedron

- Origami Polyhedra – Models made with Modular Origami

- Video of icosahedral mirror sculpture

- [1] Principle of virus architecture

Fundamental convex regular and uniform polytopes in dimensions 2–10 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | An | Bn | I2(p) / Dn | E6 / E7 / E8 / F4 / G2 | Hn |

| Regular polygon | Triangle | Square | p-gon | Hexagon | Pentagon |

| Uniform polyhedron | Tetrahedron | Octahedron • Cube | Demicube | Dodecahedron • Icosahedron | |

| Uniform polychoron | Pentachoron | 16-cell • Tesseract | Demitesseract | 24-cell | 120-cell • 600-cell |

| Uniform 5-polytope | 5-simplex | 5-orthoplex • 5-cube | 5-demicube | ||

| Uniform 6-polytope | 6-simplex | 6-orthoplex • 6-cube | 6-demicube | 122 • 221 | |

| Uniform 7-polytope | 7-simplex | 7-orthoplex • 7-cube | 7-demicube | 132 • 231 • 321 | |

| Uniform 8-polytope | 8-simplex | 8-orthoplex • 8-cube | 8-demicube | 142 • 241 • 421 | |

| Uniform 9-polytope | 9-simplex | 9-orthoplex • 9-cube | 9-demicube | ||

| Uniform 10-polytope | 10-simplex | 10-orthoplex • 10-cube | 10-demicube | ||

| Uniform n-polytope | n-simplex | n-orthoplex • n-cube | n-demicube | 1k2 • 2k1 • k21 | n-pentagonal polytope |

| Topics: Polytope families • Regular polytope • List of regular polytopes and compounds |

| Notable stellations of the icosahedron | |||||||||

| Regular | Uniform duals | Regular compounds | Regular star | Others | |||||

| (Convex) icosahedron | Small triambic icosahedron | Medial triambic icosahedron | Great triambic icosahedron | Compound of five octahedra | Compound of five tetrahedra | Compound of ten tetrahedra | Great icosahedron | Excavated dodecahedron | Final stellation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The stellation process on the icosahedron creates a number of related polyhedra and compounds with icosahedral symmetry. |

План урока:

Понятие правильного многогранника

Пять правильных многогранников

Задачи на правильные многогранники

Понятие правильного многогранника

Ранее мы уже рассматривали такой выпуклый многогранник, как куб. Легко заметить, что каждая грань куба – это квадрат, то есть правильный многоугольник. Более того, все грани куба одинаковы, а из каждой вершины исходит одинаковое количество ребер (по три ребра).

Однако куб – не единственная фигура, обладающая такими свойствами. Так же нам знаком правильный тетраэдр. У него каждая грань – это равносторонний треугольник (а это правильный многоуг-к), а из каждой вершины также выходит по 3 ребра тетраэдра.

И куб, и правильный тетраэдр являются примерами так называемых правильных многогранников. Дадим определение понятию правильного многогранника:

Иногда правильные многогранники именуют иначе – платоновыми телами. Дело в том, что древнегреческий философ Платон использовал их в своей философии, однако огромный вклад в их исследование внес другой ученый – Теэтет Афинский.

Ясно, что все ребра правильных многогранников имеют одинаковую длину. Можно доказать, что и двугранные углы, образованные смежными гранями таких многогранников, также одинаковы.

Пять правильных многогранников

Вероятно, куб и правильный тетраэдр являются первыми правильными многогранниками, открытыми человечеством. Уже во времена Пифагора люди знали и о третьем правильном многограннике – октаэдре. Каждая его грань – это равносторонний треуг-к, но, в отличие от тетраэдра, из каждой его вершины исходит уже не три, а четыре ребра. Выглядит правильный октаэдр так:

Можно доказать, что октаэдр состоит из двух правильных пирамид, у которых общее основание, но вершины располагаются по разные стороны от плоскости основания. Название октаэдра происходит от греческого слова «окта», означающее число 8. Легко увидеть, что у октаэдра как раз 8 граней. Также видно, что он имеет 6 вершин и 12 ребер.

Следующие два правильных многогранника как раз и были открыты Теэтетем Афинским. Это икосаэдр и додекаэдр. Икосаэдр также состоит из равносторонних треуг-ков, но каждая его вершина принадлежит сразу 5 ребрам.Правильный икосаэдр довольно сложно нарисовать на плоскости, поэтому его внешний вид мы покажем с помощью анимации:

Гранями додекаэдра являются правильные пятиугольники, причем в каждой его вершине соприкасаются ровно 3 грани, и, соответственно, сходятся 3 ребра. Нарисовать правильный додекаэдр ещё тяжелее, поэтому снова посмотрим на него с помощью gif-анимации:

Для подсчета количества ребер, граней и вершин у додекаэдра и икосаэдра можно применить теорему Эйлера. Начнем с икосаэдра. Обозначим количество его граней буквой Г. Теперь подсчитаем ребра (Р), принадлежащие каждой грани. Так как эти грани являются треуг-ками, то получится 3Г ребер. Но при этом каждое ребро мы посчитали дважды, ведь ребра принадлежат строго двум граням. То есть у икосаэдра количество ребер равно 3Г/2 = 1,5Г.

Также подсчитаем и вершины (В), находящиеся вокруг граней. На каждую грань приходится 3 вершины, но при этом каждая вершины принадлежит уже 5 граням. Тогда общее количество вершин составит 3Г/5 = 0,6Г.

Записываем теорему Эйлера и подставляем в ней полученные значения:

Теперь проведем аналогичные расчеты для додекаэдра. Его грани – пятиугольники, поэтому количество его ребер составляет 5Г/2. В каждой вершине додекаэдра сходятся три грани, а потому количество вершин составит 5Г/3. Используем теорему Эйлера:

Теперь составим таблицу, в которой отразим основные сведения о пяти известным нам правильных многогранниках:

Возникает вопрос – существуют ли ещё какие-нибудь правильные многогранники? Оказывается, что нет. Действительно, каждая вершина правильного многогранника является одновременно и вершиной многогранного угла. Напомним, что сумма плоских углов в многогранном угле всегда меньше 360°. Легко подсчитать, что в правильном шестиугольнике каждый угол составляет 120°, а в многоуг-ках с большим количеством сторон (семиугольник, восьмиугольник…) этот угол ещё больше. Это значит, что если трехгранный угол образован тремя шестигранниками, то сумма его плоских углов составит ровно 120°•3 = 360°, что невозможно. Также невозможно, чтобы трехгранный угол и любой другой многогранный угол был образован правильными семиугольниками, восьмиугольниками и т. д. То есть грани правильного многогранника могут быть исключительно треуг-ками, четырехуг-ками или пятиугольниками.

Рассмотрим случай, когда грани – это треуг-ки. У равностороннего треуг-ка угол составляет 60°. У тетраэдра в вершине смыкаются 3 грани, у октаэдра – 4 грани, а у икосаэдра – 5 граней. А 6 треуг-ков уже не могут образовать многогранный угол, ведь сумма углов составит 6•60° = 360°.

Теперь рассмотрим случай с четырехуг-ком. Правильный четырехуг-к – это квадрат с углом 90°. Варианту с 3 смыкающимися квадратами соответствует куб, а 4 квадрата уже не образуют многогранный угол, ведь сумма углов снова составит 4•90° = 360°.

Остался случай с пятиугольником. У правильного пятиугольника угол равен 108°. Значит, 4 таких фигуры не смогут сомкнуться и образовать многогранный угол, а варианту с тремя пятиугольниками соответствует додекаэдр.

Итак, мы рассмотрели все возможные варианты, и оказалось, что никаких других правильных многогранников, кроме пяти описанных, существовать не может, ч. т. д. Отметим также, что этот факт можно доказать и без применения свойства многогранного угла, используя только теорему Эйлера.

Задачи на правильные многогранники

Задание. Центры смежных граней куба со стороной, равной единице, соединили отрезками. Докажите, что получившийся в результате этого многогранник – это октаэдр, и найдите длину его стороны.

Решение. Грани куба – это квадраты. Напомним, что у любого правильного многоуг-ка, в том числе и квадрата, можно опустить из центра перпендикуляры на стороны, которые будут радиусами вписанной окружности. Все эти радиусы будут иметь одну и ту же длину, при этом они будут падать на середины сторон многоуг-ка. При этом у квадрата радиус вписанной окружности будет вдвое меньше стороны квадрата. В частности, у рассматриваемого куба перпендикуляры, опущенные на середины ребер, будут иметь длину 1:2 = 0,5:

Теперь возьмем любые два центра смежных граней А и В и опустим из них перпендикуляры на ребро, по которому эти грани пересекаются. Перпендикуляры упадут в одну точку – середину ребра Н:

В результате мы получили прямоугольный ∆АВН. Найдем длину его гипотенузы АВ:

Так как мы выбрали центры смежных граней произвольно, то ясно, что расстояние между любыми двумя другими вершинами многогранника, вписанного в куб, будет иметь такую же длину. Тогда каждая его грань оказывается равносторонним треуг-ком. В каждой вершине смыкается 4 ребра, поэтому многогранник оказывается октаэдром.

Задание. Вычислите площадь поверхности икосаэдра, если его ребро имеет длину 1.

Решение. Найдем площадь одной грани икосаэдра. Она представляет собой равносторонний треуг-к со стороной 1. Удобно вычислить его площадь по формуле Герона. Сначала найдем полупериметр треуг-ка:

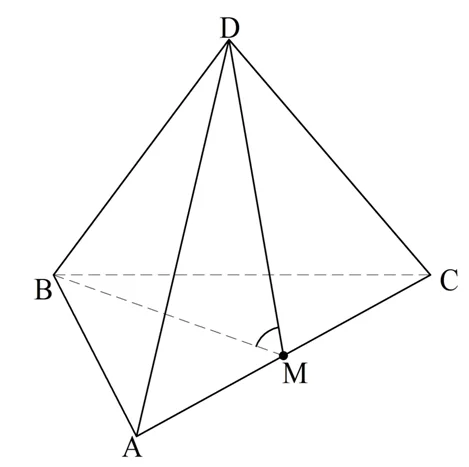

Задание. Найдите двугранный угол, который образуют грани правильного тетраэдра

Решение. Обозначим вершины тетраэдра буквами А, В, С и D. Далее соединим середину ребра АС, обозначенную как М, с вершинами B и D:

Так как М – середина АС, то ВМ и DM будут медианами ∆АВС и ∆ADC. Но эти треуг-ки равносторонние, поэтому ВМ и DM ещё и высоты. То есть ВМ⊥АС и DM⊥АС. Тогда по определению ∠DMB и будет плоским углом двугранного угла, то есть его как раз и надо вычислить. Предварительно обозначим длину грани тетраэдра буквой а.

∠ВАС составляет 60° как угол равностороннего ∆АВС. Тогда ВМ можно найти из прямоугольного ∆АВМ:

Аналогично из ∆DMC получаем, что и DM имеет такую же длину.

Теперь используем теорему косинусов для ∆BDM:

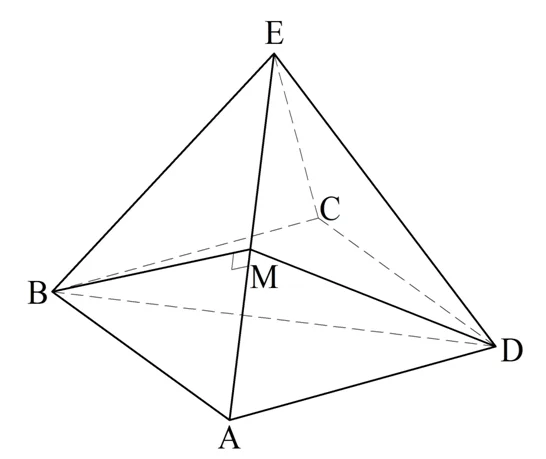

Задание. Вычислите двугранный угол, который образуют смежные грани октаэдра

Решение. Мы уже говорили, что октаэдр состоит из двух правильных четырехугольных пирамид с общим основанием. Поэтому нам надо просто найти двугранный угол между двумя боковыми гранями такой пирамиды:

Для этого на ребре АЕ отметим середину М и соединим ее с вершинами B и D. Как и в предыдущей задаче с тетраэдром, ВМ и МD окажутся медианами и высотами в равносторонних ∆АЕВ и ∆АЕD, а потому ∠ВМD является искомым.

Обозначим сторону октаэдра буквой а. Тогда длина ВМ и МD, медиан в равносторонних треуг-ках будет такой же, как и в предыдущей задаче:

Задание. Вычислите двугранный угол, образованный смежными гранями додекаэдра

Решение. Нет необходимости строить весь додекаэдр для решения задачи. Построим только трехгранный угол, образованный ребрами, выходящими из одной вершины. То есть нам достаточно рассмотреть только область, выделенную на додекаэдре красным цветом:

Каждый плоский угол такого трехгранного угла будет равен углу правильного пятиугольника, который в свою очередь рассчитывается так:

Итак, надо найти двугранный угол между гранями ADC и ADB. Они пересекаются по прямой AD. Опустим из В и С перпендикуляры на AD. ∆ABD и ∆ADC равны, ведь у них есть одинаковый угол 108°, сторона AD– общая, а BD и DC одинаковы как ребра правильного многогранника. Это значит, что перпендикуляры на AD упадут в одну точку, которую мы обозначим как H. Нам надо вычислить ∠BНС.Обратите внимание, что так как ∆ABD и ∆ADC тупоугольные, то точка Н будет находиться не на отрезке AD, а на его продолжении.

Обозначим длину ребра додекаэдра буквой а. Мы можем найти ∠HDC:

Примечание. Здесь мы использовали одну из тригонометрических формул приведения.

Аналогично из ∆BHD получаем, что BH имеет такую же длину. Теперь из ∆BDC вычисляем величину ВС2:

Задание. Вычислите площадь поверхность додекаэдра, если его ребро имеет длину 1

Решение. Каждая грань додекаэдра – правильный пятиугольник. Для нахождения его площади используем уже известные нам формулы для правильных многоугольников:

Здесь n – число сторон у многоуг-ка, Р – его периметр, S – площадь, an – длина стороны, R и r – радиусы соответственно описанной и вписанной окружности. По условию

Теперь вспомним, что у додекаэдра 12 граней. Значит, площадь всей его поверхности будет в 12 раз больше:

Ответ: ≈ 20,646.

Сегодня мы познакомились с особыми телами – правильными многогранниками. Важно запомнить, что существует всего 5 типов правильных многогранников. Эти фигуры встречаются не только в геометрии, но и в других науках. Например, атомы в никеле и меди могут выстраиваться в форме октаэдра, а оболочки некоторых вирусов похожи на икосаэдр. Правильные многогранники могут использоваться в настольных играх в качестве игральных костей. Чаще всего применяются кости в виде куба, но встречаются кости в виде додекаэдра и икосаэдра.

Расчет площади поверхности правильного икосаэдра с помощью формулы

Икосаэдр – это многогранник, который имеет 20 равных правильных треугольников как грани. Расчет площади поверхности такого икосаэдра может быть произведен с помощью формулы.

Формула для расчета площади поверхности икосаэдра

Площадь поверхности правильного икосаэдра может быть вычислена с помощью следующей формулы:

S = 5a^2√3

где S – площадь поверхности икосаэдра, а – длина ребра.

Пример расчета

Для примера возьмем икосаэдр со стороной a = 3 см.

Вычислим площадь поверхности икосаэдра по формуле:

S = 5 x 3^2 x √3 ≈ 77.94 см²

Таким образом, площадь поверхности икосаэдра равна примерно 77.94 см².

Применение расчета площади поверхности икосаэдра

Расчет площади поверхности икосаэдра может быть применен в различных областях, связанных с геометрией и конструированием. Например, этот расчет может быть полезен при проектировании архитектурных объектов или изготовлении сложных инженерных конструкций.

Заключение

Площадь поверхности правильного икосаэдра может быть вычислена с помощью формулы S = 5a^2√3, где S – площадь поверхности, а – длина ребра. Этот расчет может быть полезен в различных областях, связанных с геометрией и конструированием.

Правильный икосаэдр

Материал из свободной энциклопедии

| Правильный икосаэдр | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Тип | Правильный многогранник |

| Грань | Правильный треугольник |

| Граней | 20 |

| Рёбер | 30 |

| Вершин | 12 |

| Граней при вершине | 5 |

| Группа симметрии | Икосаэдрическая (Ih) |

| Двойственный многогранник | Правильный додекаэдр |

| Двугранный угол | 138.19° |

Икосаэдр и его описанная сфера

Пра́вильный икоса́эдр (от др.-греч. εἴκοσι «двадцать»; ἕδρον «сиденье», «основание») — правильный выпуклый многогранник, двадцатигранник[1], одно из Платоновых тел. Каждая из 20 граней представляет собой равносторонний треугольник. Число ребер равно 30, число вершин — 12.

Икосаэдр имеет 59 звёздчатых форм.

Вписанный икосаэдр, видно, что, согласно доказанному Паппом Александрийским, его вершины лежат в четырёх параллельных плоскостях.

Содержание

- 1 История

- 2 Основные формулы

- 3 Свойства

- 4 Усечённый икосаэдр

- 5 В мире

- 5.1 Тела в виде икосаэдра

- 6 См. также

- 7 Примечания

- 8 Литература

История

Евклид в предложении 16 книги XIII «Начал» занимается построением икосаэдра, получая сначала два правильных пятиугольника, лежащих в двух параллельных плоскостях — из десяти его вершин, и затем — две оставшиеся противоположные друг другу вершины[2][3]:127-131. Папп Александрийский в «Математическом собрании» занимается построением икосаэдра, вписанного в данную сферу, попутно доказывая, что двенадцать его вершин лежат в четырёх параллельных плоскостях, образуя в них четыре правильных треугольника[3]:315-316[4].

Основные формулы

Площадь поверхности S, объём V икосаэдра с длиной ребра a,

а также радиусы вписанной и описанной сфер вычисляются по формулам:

Площадь:

Объём:

Радиус вписанной сферы[5]:

Радиус описанной сферы[5]:

Свойства

- Двугранный угол между любыми двумя смежными гранями икосаэдра равен arccos(-√5/3) = 138,189685°.

- Все двенадцать вершин икосаэдра лежат по три в четырёх параллельных плоскостях, образуя в каждой из них правильный треугольник.

- Десять вершин икосаэдра лежат в двух параллельных плоскостях, образуя в них два правильных пятиугольника, а остальные две — противоположны друг другу и лежат на двух концах диаметра описанной сферы, перпендикулярного этим плоскостям.

- Икосаэдр можно вписать в куб, при этом шесть взаимно перпендикулярных рёбер икосаэдра будут расположены соответственно на шести гранях куба, остальные 24 ребра внутри куба, все двенадцать вершин икосаэдра будут лежать на шести гранях куба

- В икосаэдр может быть вписан тетраэдр, так что четыре вершины тетраэдра будут совмещены с четырьмя вершинами икосаэдра.

- Икосаэдр можно вписать в додекаэдр, при этом вершины икосаэдра будут совмещены с центрами граней додекаэдра.

- В икосаэдр можно вписать додекаэдр с совмещением вершин додекаэдра и центров граней икосаэдра.

- Усечённый икосаэдр может быть получен срезанием 12 вершин с образованием граней в виде правильных пятиугольников. При этом число вершин нового многогранника увеличивается в 5 раз (12×5=60), 20 треугольных граней превращаются в правильные шестиугольники (всего граней становится 20+12=32), а число рёбер возрастает до 30+12×5=90.

- Собрать модель икосаэдра можно при помощи 20 равносторонних треугольников.

- Невозможно собрать икосаэдр из правильных тетраэдров, так как радиус описанной сферы вокруг икосаэдра, соответственно и длина бокового ребра (от вершины до центра такой сборки) тетраэдра меньше ребра самого икосаэдра.

Усечённый икосаэдр

Усечённый икосаэдр — многогранник, состоящий из 12 правильных пятиугольников и 20 правильных шестиугольников. Имеет икосаэдрический тип симметрии. По сути классический футбольный мяч имеет форму не шара, а усечённого икосаэдра с выпуклыми (сферическими) гранями.

В мире

- Икосаэдр лучше всего из всех правильных многогранников подходит для триангуляции сферы методом рекурсивного разбиения[6]. Поскольку он содержит наибольшее среди них количество граней, искажение получающихся треугольников по отношению к правильным минимально.

- Икосаэдр применяется как игральная кость в настольных ролевых играх, и обозначается при этом d20 (dice — кости).

Тела в виде икосаэдра

- Капсиды многих вирусов (например, бактериофаги, мимивирус).

См. также

- Звёздчатый многогранник

Примечания

- ↑ Селиванов Д. Ф.,. Тело геометрическое // Энциклопедический словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона : в 86 т. (82 т. и 4 доп.). — СПб., 1890—1907.

- ↑ Euclid’s Elements, Book XIII, Proposition 16.

- ↑ 1 2 Начала Евклида. Книги XI—XV. — М.—Л.: Государственное издательство технико-теоретической литературы, 1950. — Помимо перевода на русский язык сочинения Евклида это издание в комментариях содержит перевод предложений Паппа о правильных многогранниках.

- ↑ Оригинальный текст на древнегреческом языке с параллельным переводом на латинский язык: Pappi Alexandrini Collectionis. — 1876. — Vol. I. — P. 150—157.

- ↑ 1 2 Доказательство приведено в: Cobb, John W. The Icosahedron (англ.) (2005-2007). Проверено 3 сентября 2014.

- ↑ OpenGL Red Book Ch.2 Архивировано 8 января 2015 года.

Литература

- Клейн Ф. Лекции об икосаэдре и решение уравнений пятой степени / Ф. Клейн; пер. с нем. А. Л. Городенцев, А. А. Кириллов, ред. А. Н. Тюрин. — М.: Наука, 1989. — 332 с. — ISBN 5020141976.

Звёздчатые формы икосаэдра

Икосаэдр.

Икосаэдр – один из пяти типов правильных многогранников, имеет 20 граней (треугольных), 30 ребер, 12 вершин (в каждой вершине сходятся 5 ребер).

Икосаэдр, как правильный многогранник

Основные формулы икосаэдра

Свойства икосаэдра

Икосаэдр, как правильный многогранник:

Икосаэдр (от др.-греч. εἴκοσι «двадцать»; ἕδρον «сиденье», «основание») – один из пяти типов правильных многогранников, имеет 20 граней (треугольных), 30 ребер, 12 вершин (в каждой вершине сходятся 5 ребер).

Если а – длина ребра икосаэдра, то его объем V = 5/12 · a3 · (3+51/2) ≈ 2,1817 · a3.

Икосаэдр имеет 59 звездчатых форм.

Вершины вписанного икосаэдра лежат в четырёх параллельных плоскостях.

Основные формулы икосаэдра:

Площадь поверхности S, объём V икосаэдра с длиной ребра a, а также радиусы вписанной и описанной сфер вычисляются по формулам:

Площадь поверхности икосаэдра: S = 5 · a2 · 31/2.

Объём икосаэдра: V = 5/12 · a3 · (3+51/2).

Радиус вписанной сферы икосаэдра: R = 1/12 · (42+18 · (5·а)1/2)1/2 = 1/4 · 31/2 · (3+51/2) · а.

Радиус описанной сферы икосаэдра: R = 1/4 · (2 · (5+51/2))1/2 · a.

Свойства икосаэдра:

– двугранный угол между любыми двумя смежными гранями икосаэдра равен arccos(-√5/3) = 138,189685°;

– телесный угол при вершине икосаэдра равен 2·π – 5·arcsin(2/3) ≈ 2,63455 cp (стерадиан);

– все двенадцать вершин икосаэдра лежат по три в четырёх параллельных плоскостях, образуя в каждой из них правильный треугольник;

– десять вершин икосаэдра лежат в двух параллельных плоскостях, образуя в них два правильных пятиугольника, а остальные две — противоположны друг другу и лежат на двух концах диаметра описанной сферы, перпендикулярного этим плоскостям;

– икосаэдр можно вписать в куб, при этом шесть взаимно перпендикулярных рёбер икосаэдра будут расположены соответственно на шести гранях куба, остальные 24 ребра внутри куба, все двенадцать вершин икосаэдра будут лежать на шести гранях куба;

– в икосаэдр может быть вписан тетраэдр, так что четыре вершины тетраэдра будут совмещены с четырьмя вершинами икосаэдра;

– икосаэдр можно вписать в додекаэдр, при этом вершины икосаэдра будут совмещены с центрами граней додекаэдра;

– в икосаэдр можно вписать додекаэдр с совмещением вершин додекаэдра и центров граней икосаэдра;

– усечённый икосаэдр может быть получен срезанием 12 вершин с образованием граней в виде правильных пятиугольников. При этом число вершин нового многогранника увеличивается в 5 раз (12×5=60), 20 треугольных граней превращаются в правильные шестиугольники (всего граней становится 20+12=32), а число рёбер возрастает до 30+12×5=90;

– собрать модель икосаэдра можно при помощи 20 равносторонних треугольников;

– невозможно собрать икосаэдр из правильных тетраэдров, так как радиус описанной сферы вокруг икосаэдра, соответственно и длина бокового ребра (от вершины до центра такой сборки) тетраэдра меньше ребра самого икосаэдра.

Источник: https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Правильный_икосаэдр

Примечание: © Фото //www.pexels.com, //pixabay.com

Коэффициент востребованности

2 922