Random converter

- Калькуляторы

- Астрономия

Калькулятор расстояния и годичного параллакса

Сириус (α Большого Пса)

Калькулятор определяет расстояние до недалекой звезды в световых годах и парсеках, если известен годичный параллакс этой звезды в угловых секундах. Можно также определить параллакс, если известно расстояние.

Пример: рассчитать расстояние в световых годах до самой яркой звезды звездного неба северного полушария Арктура (α Волопаса) в созвездии Волопаса, если известно что ее параллакс равен 88.83 угловым миллисекундам.

Параллакс

p

Расстояние

D

Поделиться ссылкой на этот калькулятор, включая входные параметры

Определение параллакса и формула для расчета расстояния

Параллакс — это изменение видимого кажущегося положения объекта, наблюдаемого с разных точек и измеренное как угол (или половинный угол) между направлениями от наблюдателя на объект. Годичный звездный параллакс — это изменение положения звезды, наблюдаемой с двух находящихся на большом расстоянии друг от друга точек. Эти две точки наблюдения расположены на земной орбите, как показано ниже. Параллакс небесного тела можно использовать для нахождения расстояния до него по формуле:

Здесь D — расстояние до небесного тела, измеренное в парсеках, и p — наблюдаемый годичный параллакс, измеренный в дуговых секундах. Эта формула и используется для расчетов в нашем калькуляторе. Парсек определяется как расстояние до объекта, годичный звездный параллакс которого равен 1 дуговой секунде. Иными словами, парсек — это расстояние, с которого диск размером в 1 а.е. будет иметь угловой размер в 1 угловую секунду.

Годичный параллакс звезды (чертеж не в масштабе); 1 — астрономическая единица (а.е.), то есть расстояние от Земли до Солнца; D — расстояние от центра земной орбиты до звезды S; p — параллакс, измеренный в угловых секундах («)

Подробнее о длине и расстоянии: измерение расстояний в космосе

Общие сведения

Космос огромен — поэтому космические расстояния измеряются не так, как это делается на Земле. В статье о длине и расстояниях мы говорили главным образом об измерении относительно небольших расстояний, которые не трудно себе представить. Однако расстояния в космосе представить себе очень трудно из-за их огромной величины, а привычные метры и километры едва ли годятся для использования в космосе. Для измерения расстояний между планетами и галактиками вряд ли можно использовать измерительные приборы типа рулетки или линейки. Спутниковая навигация в космосе тоже не работает. Поэтому для космоса придется ввести не только новые единицы измерения, но и новые методы измерения этих расстояний.

Измерения с помощью радиолокации

Расположенная на Земле радиолокационная станция (РЛС) посылает СВЧ-излучение в сторону астрономического объекта, расстояние до которого нужно вычислить. Затем измеряется время, которое необходимо, чтобы сигнал достиг объекта и вернулся назад, к РЛС. Зная это время и скорость света в вакууме, можно определить расстояние, умножая скорость на время.

Использовать РЛС для этих измерений удобно не только для определения расстояния до нужного астрономического объекта, но и для оценки скорости изменения этого расстояния (ведь объекты во Вселенной движутся друг относительно друга!). Это, в свою очередь, полезно при слежении за перемещениями объектов в космосе, например, для оценки возможности столкновения астероида с Землей.

Этот метод ограничен астрономическими объектами, которые находятся на небольших расстояниях от Земли. Можно сказать, что он пригоден для объектов, находящихся в пределах Солнечной системы. Это связано с тем, что радиосигнал ослабляется и рассеивается на больших расстояниях. Кроме того, чем больше расстояние, тем больше должен быть объект для того, чтобы его могла «увидеть» радиолокационная станция.

Годичный звездный параллакс

В статье о длине и расстоянии мы уже обсуждали годичный звездный параллакс. Здесь мы кратко рассмотрим это явление, потому что именно параллакс используется для измерения расстояний в космосе. Параллакс — геометрические явление, используемое для определения расстояний. Он хорошо выражен, если наблюдать объект с разных точек зрения относительно удаленного фона. Познать суть параллакса достаточно легко: вытяните перед собой палец или карандаш и закройте один глаз. Отметьте насколько далеко этот палец от другого объекта (скажем, от дерева, если вы на улице, или от шкафа, если вы находитесь в помещении). Теперь закройте этот глаз и откройте другой. Заметили, что палец или карандаш переместился относительно удаленного объекта? Это перемещение и является параллаксом. Если проделать аналогичный эксперимент, удерживая палец ближе к глазам, можно заметить, что расстояние, на которое перемещается палец или карандаш относительно удаленного объекта, стало больше. Чем ближе палец к глазам, тем больше он сдвигается относительно удаленного объекта при рассматривании пальца обоими глазами. Понятно, что это явление можно использовать для измерения расстояния до объекта, в данном случае — пальца.

На этом рисунке два положения Земли обозначены голубыми кружками, а Солнце — оранжевое. А — реальное положение звезды, расстояние до которой необходимо измерить. А2 и А3 — кажущиеся положения этой звезды с двух точек наблюдения относительно удаленной белой звезды DS. Р — параллактический угол. Измеряемое расстояние между Солнцем и звездой, обозначенное оранжевой линией AS, равно одному парсеку, если угол Р равен одной дуговой секунде.

Более подробное математическое объяснение измерения расстояний с помощью параллакса приводится в статье о длине и расстоянии. В общем случае, можно сказать, что расстояния следует измерять, когда Земля находится в двух противоположных точках ее орбиты вокруг Солнца (с интервалом в шесть месяцев, так как Земля делает один оборот вокруг Солнца за один год). Мы используем известное расстояние от Земли до Солнца (точно измеренное и называемое астрономической единицей) и измерим угол, образованный линией, соединяющей Землю в точке первого измерения, звезду, расстояние до которой измеряется, и точкой, в которой находится Земля во время второго измерения. Фактически, нам нужно знать только половину этого угла, которая называется параллактическим углом и обозначена на рисунке буквой P. Таким образом, имеется достаточно информации, чтобы рассчитать расстояние от Земли до звезды с помощью тригонометрических уравнений.

С помощью описанного метода можно измерить расстояние в различных единицах длины, но астрономы предпочитают парсек. Один парсек — это расстояние от Солнца до рассматриваемой звезды, если параллактический угол равен 1 дуговой секунде. Другой единицей длины является световой год (1 парсек = 3,26 светового года), однако эту единицу чаще используют журналисты. Астрономы предпочитают парсеки.

Четыре звезды имеют один и тот же размер, но расположены на разных расстояниях от нас. Звезда в положении 1 находится ближе всего, а звезда в положении 4 на максимальном удалении от нас. В результате мы видим ближние к нам звезды как более яркие, а удаленные — как менее яркие. Если известная их реальная яркость, можно сравнить ее с их кажущейся яркостью и, таким образом, узнать расстояние до них

Как и при радиолокационных измерениях, этот метод ограничен расстоянием, на которое удалена звезда. Если она слишком далеко (более 500 парсеков), то угол, который нужно измерить, слишком мал и измерить его практически невозможно. Поэтому для больших расстояний данный метод не работает.

Цефеиды

Для измерения расстояний в космосе можно использовать определенные типы звезд, называемых Цефеидами. Цефеида — пульсирующая звезда с точной зависимостью светимости (яркости) от периода пульсации. Чем больше этот период, тем выше яркость Цефеид. Эта корреляция между периодом пульсации я светимостью хорошо известна и все Цефеиды ведут себя одинаково. Поэтому, если известен период пульсации, который несложно наблюдать, можно измерить светимость звезды. Мы знаем, что чем дальше звезда, тем меньше ее яркость. Таким образом, если сравнить реальную яркость с кажущейся, можно определить расстояние до звезды.

Пульсация цефеид обусловлена их сжатием и расширением. При этом их яркость изменяется, и для определения периода нужно измерить время между точками с максимальной яркостью. Ядро звезды не изменяет размеры, однако их внешние газовые слои расширяются и сжимаются вследствие флуктуаций давления газа в этих слоях. Сжатие и расширение происходит за счет двух сил: гравитационного притяжения, которое приводит к сближению молекул газа в направлении центра звезды, и давления газа, которое приводит к расширению внешнего слоя.

Схематическое изображение пульсирующей Цефеиды с периодом в два дня. Пики светимости 1 декабря 2010 г., когда звезда начинает постепенно терять яркость. 2 декабря яркость минимальная. Затем звезда снова достигает максимальной светимости 3 декабря и уменьшает светимость 4 декабря и так далее

Когда звезда находится в сжатом состоянии, ее фотоны имеют высокую энергию и в результате давление повышается, что приводит к расширению внешней оболочки звезды. Когда это давление падает и становится меньше гравитационных сил, сжимающих оболочку, звезда сжимается. Затем процесс повторяется.

Цефеиды можно использовать для измерения расстояний до 40 миллионов парсеков, то есть намного больших, чем позволяет метод параллакса. Недостаток метода — цефеиды не так уж часто встречаются.

Сверхновая типа Ia

Еще одним стандартным измерителем расстояния являются сверхновые типа Ia. Идея аналогичная использованию Цефеид: при известной реальной светимости сверхновой в момент взрыва, когда яркость максимальна, можно сравнить ее с видимой яркостью звезды и, таким образом, определить насколько далеко она от нас. Именно эта категория сверхновых интересует нас в связи с тем, что они наиболее хорошо изучены, а их поведение предсказуемо, поэтому максимальная светимость во время взрыва хорошо известна. Эти взрывы происходит с двумя астрономическими объектами — с белыми карликами и еще одним белым карликом или со звездой-гигантом. Белый карлик представляет собой звезду очень высокой плотности в конце ее жизненного цикла, когда эта звезда «всасывает» материю находящихся рядом звезд (в нашем случае — второй звезды) до тех пор, пока не взорвется. Эти взрывы сверхновых позволяет измерять расстояния до галактик, в которых они находятся.

Другие методы измерения расстояний

Имеется еще несколько методов измерения расстояний в космосе. Один из них основан на предположении, что вселенная расширяется с известной скоростью. Если известна скорость, с которой галактики удаляются от нашей галактики, то с помощью закона Хаббла можно рассчитать насколько далеко они от нас. Закон Хаббла гласит, что расстояние до галактики равно скорости галактики, деленной на постоянную Хаббла, которая является известной константой. Скорость галактики можно определить, изучая спектр галактики, а затем, учитывая эффект Доплера, можно определить расстояние. Эффект Доплера, более известный в астрономии как смещение Доплера — это изменение частоты электромагнитного излучения (в нашем случае — света), излучаемого объектом, который движется относительно наблюдателя. При движении в сторону от наблюдателя этот спектр сдвигается в сторону низких частот, то есть в красную сторону, причем степень сдвига зависит от скорости удаления галактики. По смещению можно рассчитать скорость, а затем вычислить расстояние.

Примеры расчета расстояния до некоторых звезд и их звездного параллакса

Параллакс в дуговых миллисекундах и расстояние в световых годах

Канопус (α Киля)

Ригель Кентаурус (α Центавра A)

Сириус (α Большого Пса)

Вега (α Лиры)

Капелла (α Возничего)

Ригель (β Ориона)

Альтаир (α Орла)

Альдебаран (α Тельца)

Антарес (α Скорпиона)

Арктур (α Волопаса)

Unit Converter articles were edited and illustrated by Анатолий Золотков

|

Location of Sirius (circled) |

|

| Observation data Epoch J2000.0 Equinox ICRS |

|

|---|---|

| Constellation | Canis Major |

| Pronunciation | [1] |

| Sirius A | |

| Right ascension | 06h 45m 08.917s[2] |

| Declination | −16° 42′ 58.02″[2] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | −1.46[3] |

| Sirius B | |

| Right ascension | 06h 45m 09.0s[4] |

| Declination | −16° 43′ 06″[4] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 8.44[5] |

| Characteristics | |

| Sirius A | |

| Evolutionary stage | Main sequence |

| Spectral type | A0mA1 Va[6] |

| U−B colour index | −0.05[3] |

| B−V colour index | +0.00[3] |

| Sirius B | |

| Evolutionary stage | White dwarf |

| Spectral type | DA2[5] |

| U−B colour index | −1.04[7] |

| B−V colour index | −0.03[7] |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | −5.50[8] km/s |

| Sirius A | |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: −546.01 mas/yr[9] Dec.: −1,223.07 mas/yr[9] |

| Parallax (π) | 379.21 ± 1.58 mas[9] |

| Distance | 8.60 ± 0.04 ly (2.64 ± 0.01 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | +1.43[10] |

| Sirius B | |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: −461.571 mas/yr[11] Dec.: −914.520 mas/yr[11] |

| Parallax (π) | 374.4896 ± 0.2313 mas[11] |

| Distance | 8.709 ± 0.005 ly (2.670 ± 0.002 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | +11.18[7] |

| Orbit[12] | |

| Primary | α Canis Majoris A |

| Companion | α Canis Majoris B |

| Period (P) | 50.1284 ± 0.0043 yr |

| Semi-major axis (a) | 7.4957 ± 0.0025″ |

| Eccentricity (e) | 0.59142 ± 0.00037 |

| Inclination (i) | 136.336 ± 0.040° |

| Longitude of the node (Ω) | 45.400 ± 0.071° |

| Periastron epoch (T) | 1,994.5715 ± 0.0058 |

| Argument of periastron (ω) (secondary) |

149.161 ± 0.075° |

| Details | |

| Sirius A | |

| Mass | 2.063±0.023[12] M☉ |

| Radius | 1.711[13] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 25.4[13] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 4.33[14] cgs |

| Temperature | 9,940[14] K |

| Metallicity [Fe/H] | 0.50[15] dex |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 16[16] km/s |

| Age | 242±5[12] Myr |

| Sirius B | |

| Mass | 1.018 ± 0.011[12] M☉ |

| Radius | 0.0084 ± 3%[17] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 0.056[18] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 8.57[17] cgs |

| Temperature | 25,000 ± 200[13] K |

| Age | 228+10 −8[12] Myr |

| Other designations | |

|

Dog Star, Aschere, Canicula, Al Shira, Sothis,[19] Alhabor,[20] |

|

| Sirius B: EGGR 49, WD 0642-166, GCTP 1577.00[24] | |

| Database references | |

| A | |

| B |

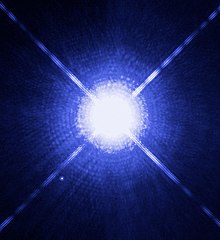

Sirius is the brightest star in the night sky. Its name is derived from the Greek word Σείριος, or Seirios, meaning lit. ‘glowing’ or ‘scorching’. The star is designated α Canis Majoris, Latinized to Alpha Canis Majoris, and abbreviated α CMa or Alpha CMa. With a visual apparent magnitude of −1.46, Sirius is almost twice as bright as Canopus, the next brightest star. Sirius is a binary star consisting of a main-sequence star of spectral type A0 or A1, termed Sirius A, and a faint white dwarf companion of spectral type DA2, termed Sirius B. The distance between the two varies between 8.2 and 31.5 astronomical units as they orbit every 50 years.[25]

Sirius appears bright because of its intrinsic luminosity and its proximity to the Solar System. At a distance of 2.64 parsecs (8.6 ly), the Sirius system is one of Earth’s nearest neighbours. Sirius is gradually moving closer to the Solar System; it is expected to increase in brightness slightly over the next 60,000 years to reach a peak magnitude of −1.68.

Coincidentally, at about the same time, Sirius will take its turn as the southern Pole Star, around the year 66270. In that year, Sirius will come to within 1.6 degrees of the south celestial pole. This is due to precession and proper motion of Sirius itself which moves slowly in the SSW direction. So it will be visible from the southern hemisphere only.

[26]

After that time, its distance will begin to increase, and it will become fainter, but it will continue to be the brightest star in the Earth’s night sky for approximately the next 210,000 years, at which point Vega, another A-type star that is intrinsically more luminous than Sirius, becomes the brightest star.[27]

Sirius A is about twice as massive as the Sun (M☉) and has an absolute visual magnitude of +1.43. It is 25 times as luminous as the Sun,[13] but has a significantly lower luminosity than other bright stars such as Canopus, Betelgeuse, or Rigel. The system is between 200 and 300 million years old.[13] It was originally composed of two bright bluish stars. The initially more massive of these, Sirius B, consumed its hydrogen fuel and became a red giant before shedding its outer layers and collapsing into its current state as a white dwarf around 120 million years ago.[13]

Sirius is colloquially known as the «Dog Star«, reflecting its prominence in its constellation, Canis Major (the Greater Dog).[19] The heliacal rising of Sirius marked the flooding of the Nile in Ancient Egypt and the «dog days» of summer for the ancient Greeks, while to the Polynesians, mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, the star marked winter and was an important reference for their navigation around the Pacific Ocean.

Observational history[edit]

| Sirius Spdt |

|---|

| Egyptian hieroglyphs |

The brightest star seen from Earth, Sirius is recorded in some of the earliest astronomical records. Its displacement from the ecliptic causes its heliacal rising to be remarkably regular compared to other stars, with a period of almost exactly 365.25 days holding it constant relative to the solar year. This rising occurs at Cairo on 19 July (Julian), placing it just before the onset of the annual flooding of the Nile during antiquity.[28] Owing to the flood’s own irregularity, the extreme precision of the star’s return made it important to the ancient Egyptians,[28] who worshipped it as the goddess Sopdet (Ancient Egyptian: Spdt, «Triangle»;[a] Greek: Σῶθις}, Sō̂this), guarantor of the fertility of their land.[b]

The ancient Greeks observed that the appearance of Sirius as the morning star heralded the hot and dry summer and feared that the star caused plants to wilt, men to weaken, and women to become aroused.[30] Owing to its brightness, Sirius would have been seen to twinkle more in the unsettled weather conditions of early summer. To Greek observers, this signified emanations that caused its malignant influence. Anyone suffering its effects was said to be «star-struck» (ἀστροβόλητος, astrobólētos). It was described as «burning» or «flaming» in literature.[31] The season following the star’s reappearance came to be known as the «dog days».[32] The inhabitants of the island of Ceos in the Aegean Sea would offer sacrifices to Sirius and Zeus to bring cooling breezes and would await the reappearance of the star in summer. If it rose clear, it would portend good fortune; if it was misty or faint then it foretold (or emanated) pestilence. Coins retrieved from the island from the 3rd century BC feature dogs or stars with emanating rays, highlighting Sirius’s importance.[31]

The Romans celebrated the heliacal setting of Sirius around 25 April, sacrificing a dog, along with incense, wine, and a sheep, to the goddess Robigo so that the star’s emanations would not cause wheat rust on wheat crops that year.[33]

Bright stars were important to the ancient Polynesians for navigation of the Pacific Ocean. They also served as latitude markers; the declination of Sirius matches the latitude of the archipelago of Fiji at 17°S and thus passes directly over the islands each sidereal day.[34] Sirius served as the body of a «Great Bird» constellation called Manu, with Canopus as the southern wingtip and Procyon the northern wingtip, which divided the Polynesian night sky into two hemispheres.[35] Just as the appearance of Sirius in the morning sky marked summer in Greece, it marked the onset of winter for the Māori, whose name Takurua described both the star and the season. Its culmination at the winter solstice was marked by celebration in Hawaii, where it was known as Ka’ulua, «Queen of Heaven». Many other Polynesian names have been recorded, including Tau-ua in the Marquesas Islands, Rehua in New Zealand, and Ta’urua-fau-papa «Festivity of original high chiefs» and Ta’urua-e-hiti-i-te-tara-te-feiai «Festivity who rises with prayers and religious ceremonies» in Tahiti.[36]

Kinematics[edit]

In 1717, Edmond Halley discovered the proper motion of the hitherto presumed fixed stars[37] after comparing contemporary astrometric measurements with those from the second century AD given in Ptolemy’s Almagest. The bright stars Aldebaran, Arcturus and Sirius were noted to have moved significantly; Sirius had progressed about 30 arcminutes (about the diameter of the Moon) to the southwest.[38]

In 1868, Sirius became the first star to have its velocity measured, the beginning of the study of celestial radial velocities. Sir William Huggins examined the spectrum of the star and observed a red shift. He concluded that Sirius was receding from the Solar System at about 40 km/s.[39][40] Compared to the modern value of −5.5 km/s, this was an overestimate and had the wrong sign; the minus sign (−) means that it is approaching the Sun.[41]

Distance[edit]

In his 1698 book, Cosmotheoros, Christiaan Huygens estimated the distance to Sirius at 27,664 times the distance from the Earth to the Sun (about 0.437 light-year, translating to a parallax of roughly 7.5 arcseconds).[42] There were several unsuccessful attempts to measure the parallax of Sirius: by Jacques Cassini (6 seconds); by some astronomers (including Nevil Maskelyne)[43] using Lacaille’s observations made at the Cape of Good Hope (4 seconds); by Piazzi (the same amount); using Lacaille’s observations made at Paris, more numerous and certain than those made at the Cape (no sensible parallax); by Bessel (no sensible parallax).[44]

Scottish astronomer Thomas Henderson used his observations made in 1832–1833 and South African astronomer Thomas Maclear’s observations made in 1836–1837, to determine that the value of the parallax was 0.23 arcsecond, and error of the parallax was estimated not to exceed a quarter of a second, or as Henderson wrote in 1839, «On the whole we may conclude that the parallax of Sirius is not greater than half a second in space; and that it is probably much less.»[45] Astronomers adopted a value of 0.25 arcsecond for much of the 19th century.[46] It is now known to have a parallax of nearly 0.4 arcseconds.

The Hipparcos parallax for Sirius is only accurate to about ±0.04 light years, giving a distance of 8.6 light years.[9] Sirius B is generally assumed to be at the same distance. Sirius B has a Gaia Data Release 3 parallax with a much smaller statistical margin of error, giving a distance of 8.709±0.005 light years, but it is flagged as having a very large value for astrometric excess noise, which indicates that the parallax value may be unreliable.[11]

Discovery of Sirius B[edit]

In a letter dated 10 August 1844, the German astronomer Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel deduced from changes in the proper motion of Sirius that it had an unseen companion.[47] On 31 January 1862, American telescope-maker and astronomer Alvan Graham Clark first observed the faint companion, which is now called Sirius B, or affectionately «the Pup».[48] This happened during testing of an 18.5-inch (470 mm) aperture great refractor telescope for Dearborn Observatory, which was one of the largest refracting telescope lenses in existence at the time, and the largest telescope in the United States.[49] Sirius B’s sighting was confirmed on 8 March with smaller telescopes.[50]

The visible star is now sometimes known as Sirius A. Since 1894, some apparent orbital irregularities in the Sirius system have been observed, suggesting a third very small companion star, but this has never been confirmed. The best fit to the data indicates a six-year orbit around Sirius A and a mass of 0.06 M☉. This star would be five to ten magnitudes fainter than the white dwarf Sirius B, which would make it difficult to observe.[51] Observations published in 2008 were unable to detect either a third star or a planet. An apparent «third star» observed in the 1920s is now believed to be a background object.[52]

In 1915, Walter Sydney Adams, using a 60-inch (1.5 m) reflector at Mount Wilson Observatory, observed the spectrum of Sirius B and determined that it was a faint whitish star.[53] This led astronomers to conclude that it was a white dwarf—the second to be discovered.[54] The diameter of Sirius A was first measured by Robert Hanbury Brown and Richard Q. Twiss in 1959 at Jodrell Bank using their stellar intensity interferometer.[55] In 2005, using the Hubble Space Telescope, astronomers determined that Sirius B has nearly the diameter of the Earth, 12,000 kilometres (7,500 mi), with a mass 102% of the Sun’s.[56]

Colour controversy[edit]

Twinkling of Sirius (apparent magnitude = −1.5) in the evening shortly before upper culmination on the southern meridian at a height of 20 degrees above the horizon. During 29 seconds Sirius moves on an arc of 7.5 minutes from the left to the right.

Around the year 150 AD,[57] Claudius Ptolemy of Alexandria, an ethnic Greek Egyptian astronomer of the Roman period, mapped the stars in Books VII and VIII of his Almagest, in which he used Sirius as the location for the globe’s central meridian.[58] He described Sirius as reddish, along with five other stars, Betelgeuse, Antares, Aldebaran, Arcturus, and Pollux, all of which are at present observed to be of orange or red hue.[57] The discrepancy was first noted by amateur astronomer Thomas Barker, squire of Lyndon Hall in Rutland, who prepared a paper and spoke at a meeting of the Royal Society in London in 1760.[59] The existence of other stars changing in brightness gave credibility to the idea that some may change in colour too; Sir John Herschel noted this in 1839, possibly influenced by witnessing Eta Carinae two years earlier.[60] Thomas J.J. See resurrected discussion on red Sirius with the publication of several papers in 1892, and a final summary in 1926.[61] He cited not only Ptolemy but also the poet Aratus, the orator Cicero, and general Germanicus all calling the star red, though acknowledging that none of the latter three authors were astronomers, the last two merely translating Aratus’s poem Phaenomena.[62] Seneca had described Sirius as being of a deeper red than Mars.[63] Not all ancient observers saw Sirius as red. The 1st-century poet Marcus Manilius described it as «sea-blue», as did the 4th-century Avienius.[64] It was the standard white star in ancient China, and multiple records from the 2nd century BC up to the 7th century AD all describe Sirius as white.[65][66]

In 1985, German astronomers Wolfhard Schlosser and Werner Bergmann published an account of an 8th-century Lombardic manuscript, which contains De cursu stellarum ratio by St. Gregory of Tours. The Latin text taught readers how to determine the times of nighttime prayers from positions of the stars, and a bright star described as rubeola («reddish») was claimed to be Sirius. The authors proposed this was further evidence Sirius B had been a red giant at the time.[67] Other scholars replied that it was likely St. Gregory had been referring to Arcturus.[68][69]

The possibility that stellar evolution of either Sirius A or Sirius B could be responsible for this discrepancy has been rejected by astronomers on the grounds that the timescale of thousands of years is much too short and that there is no sign of the nebulosity in the system that would be expected had such a change taken place.[63] An interaction with a third star, to date undiscovered, has also been proposed as a possibility for a red appearance.[70] Alternative explanations are either that the description as red is a poetic metaphor for ill fortune, or that the dramatic scintillations of the star when rising left the viewer with the impression that it was red. To the naked eye, it often appears to be flashing with red, white, and blue hues when near the horizon.[63]

Observation[edit]

Sirius (bottom) and the constellation Orion (right). The three brightest stars in this image—Sirius, Betelgeuse (top right) and Procyon (top left)—form the Winter Triangle. The bright star at top center is Alhena, which forms a cross-shaped asterism with the Winter Triangle.

With an apparent magnitude of −1.46, Sirius is the brightest star in the night sky, almost twice as bright as the second-brightest star, Canopus.[71] From Earth, Sirius always appears dimmer than Jupiter and Venus, and at certain times also dimmer than Mercury and Mars.[72] Sirius is visible from almost everywhere on Earth, except latitudes north of 73° N, and it does not rise very high when viewed from some northern cities (reaching only 13° above the horizon from Saint Petersburg).[73] Because of its declination of roughly −17°, Sirius is a circumpolar star from latitudes south of 73° S. From the Southern Hemisphere in early July, Sirius can be seen in both the evening where it sets after the Sun and in the morning where it rises before the Sun.[74] Along with Procyon and Betelgeuse, Sirius forms one of the three vertices of the Winter Triangle to observers in the Northern Hemisphere.[75]

Sirius can be observed in daylight with the naked eye under the right conditions. Ideally, the sky should be very clear, with the observer at a high altitude, the star passing overhead, and the Sun low on the horizon. These observing conditions are more easily met in the Southern Hemisphere, owing to the southerly declination of Sirius.[76]

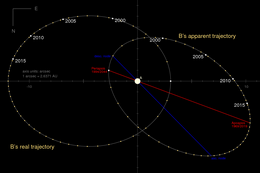

The orbital motion of the Sirius binary system brings the two stars to a minimum angular separation of 3 arcseconds and a maximum of 11 arcseconds. At the closest approach, it is an observational challenge to distinguish the white dwarf from its more luminous companion, requiring a telescope with at least 300 mm (12 in) aperture and excellent seeing conditions. After a periastron occurred in 1994,[c]

the pair moved apart, making them easier to separate with a telescope.[77] Apoastron occurred in 2019,[d]

but from the Earth’s vantage point, the greatest observational separation will occur in 2023, with an angular separation of 11.333″.[78]

At a distance of 2.6 parsecs (8.6 ly), the Sirius system contains two of the eight nearest stars to the Sun, and it is the fifth closest stellar system to the Sun.[79] This proximity is the main reason for its brightness, as with other near stars such as Alpha Centauri, Procyon and Vega and in contrast to distant, highly luminous supergiants such as Canopus, Rigel or Betelgeuse.(Note that Canopus may be a bright giant)[80] It is still around 25 times more luminous than the Sun.[13] The closest large neighbouring star to Sirius is Procyon, 1.61 parsecs (5.24 ly) away.[81] The Voyager 2 spacecraft, launched in 1977 to study the four giant planets in the Solar System, is expected to pass within 4.3 light-years (1.3 pc) of Sirius in approximately 296,000 years.[82]

Stellar system[edit]

The orbit of Sirius B around A, as seen from Earth (slanted ellipse). The wide horizontal ellipse shows the true shape of the orbit (with an arbitrary orientation) as it would appear if viewed straight on.

A Chandra X-ray Observatory image of the Sirius star system, where the spike-like pattern is due to the support structure for the transmission grating. The bright source is Sirius B. Credit: NASA/SAO/CXC

Sirius is a binary star system consisting of two white stars orbiting each other with a separation of about 20 AU[e]

(roughly the distance between the Sun and Uranus) and a period of 50.1 years. The brighter component, termed Sirius A, is a main-sequence star of spectral type early A, with an estimated surface temperature of 9,940 K.[14] Its companion, Sirius B, is a star that has already evolved off the main sequence and become a white dwarf. Currently 10,000 times less luminous in the visual spectrum, Sirius B was once the more massive of the two.[83] The age of the system has been estimated at around 230 million years. Early in its life, it is thought to have been two bluish-white stars orbiting each other in an elliptical orbit every 9.1 years.[83] The system emits a higher than expected level of infrared radiation, as measured by IRAS space-based observatory. This might be an indication of dust in the system, which is considered somewhat unusual for a binary star.[81][84] The Chandra X-ray Observatory image shows Sirius B outshining its partner as an X-ray source.[85]

In 2015, Vigan and colleagues used the VLT Survey Telescope to search for evidence of substellar companions, and were able to rule out the presence of giant planets 11 times more massive than Jupiter at 0.5 AU distance from Sirius A, 6–7 times the mass of Jupiter at 1–2 AU distance, and down to around 4 times the mass of Jupiter at 10 AU distance.[86] Similarly, Lucas and colleagues did not detect any companions around Sirius B.[87]

Sirius A[edit]

Comparison of Sirius A and the Sun, to scale and relative surface brightness

Sirius A has a mass of 2.063 M☉.[12][13][88] The radius of this star has been measured by an astronomical interferometer, giving an estimated angular diameter of 5.936±0.016 mas. The projected rotational velocity is a relatively low 16 km/s,[16] which does not produce any significant flattening of its disk.[89] This is at marked variance with the similar-sized Vega, which rotates at a much faster 274 km/s and bulges prominently around its equator.[90] A weak magnetic field has been detected on the surface of Sirius A.[91]

Stellar models suggest that the star formed during the collapsing of a molecular cloud and that, after 10 million years, its internal energy generation was derived entirely from nuclear reactions. The core became convective and used the CNO cycle for energy generation.[89] It is calculated that Sirius A will have completely exhausted the store of hydrogen at its core within a billion (109) years of its formation, and will then evolve away from the main sequence.[92] It will pass through a red giant stage and eventually become a white dwarf.[93]

Sirius A is classed as a type Am star, because the spectrum shows deep metallic absorption lines,[94] indicating an enhancement of its surface layers in elements heavier than helium, such as iron.[81][89] The spectral type has been reported as A0mA1 Va, which indicates that it would be classified as A1 from hydrogen and helium lines, but A0 from the metallic lines that cause it to be grouped with the Am stars.[6] When compared to the Sun, the proportion of iron in the atmosphere of Sirius A relative to hydrogen is given by ![{displaystyle textstyle left[{frac {{ce {Fe}}}{{ce {H}}}}right]=0.5 ,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5cce43f23ea45e616a109551041b8dc895b2943b)

Sirius B[edit]

Size comparison of Sirius B and Earth

Sirius B is one of the most massive white dwarfs known. With a mass of 1.02 M☉, it is almost double the 0.5–0.6 M☉ average. This mass is packed into a volume roughly equal to the Earth’s.[56] The current surface temperature is 25,200 K.[13] Because there is no internal heat source, Sirius B will steadily cool as the remaining heat is radiated into space over the next two billion years or so.[95]

A white dwarf forms after a star has evolved from the main sequence and then passed through a red giant stage. This occurred when Sirius B was less than half its current age, around 120 million years ago. The original star had an estimated 5 M☉[13] and was a B-type star (most likely B5V for 5 M☉)[96][97] when it was still on the main sequence, potentially burning around 600-1200 times more luminous than the sun. While it passed through the red giant stage, Sirius B may have enriched the metallicity of its companion, explaining the very high metallicity of Sirius A.

This star is primarily composed of a carbon–oxygen mixture that was generated by helium fusion in the progenitor star.[13] This is overlaid by an envelope of lighter elements, with the materials segregated by mass because of the high surface gravity.[98] The outer atmosphere of Sirius B is now almost pure hydrogen—the element with the lowest mass—and no other elements are seen in its spectrum.[99]

Apparent third star[edit]

Since 1894, irregularities have been tentatively observed in the orbits of Sirius A and B with an apparent periodicity of 6–6.4 years. A 1995 study concluded that such a companion likely exists, with a mass of roughly 0.05 solar mass—a small red dwarf or large brown dwarf, with an apparent magnitude of more than 15, and less than 3 arcseconds from Sirius A.[51]

More recent (and accurate) astrometric observations by the Hubble Space Telescope ruled out the existence of such a Sirius C entirely. The 1995 study predicted an astrometric movement of roughly 90 mas (0.09 arcsecond), but Hubble was unable to detect any location anomaly to an accuracy of 5 mas (0.005 arcsec). This ruled out any objects orbiting Sirius A with more than 0.033 solar mass (35 Jupiter masses) orbiting in 0.5 years, and 0.014 (15 Jupiter masses) in 2 years. The study was also able to rule out any companions to Sirius B with more than 0.024 solar mass (25 Jupiter masses) orbiting in 0.5 year, and 0.0095 (10 Jupiter masses) orbiting in 1.8 years. Effectively, there are almost certainly no additional bodies in the Sirius system larger than a small brown dwarf or large exoplanet.[100][12]

Star cluster membership[edit]

In 1909, Ejnar Hertzsprung was the first to suggest that Sirius was a member of the Ursa Major Moving Group, based on his observations of the system’s movements across the sky. The Ursa Major Group is a set of 220 stars that share a common motion through space. It was once a member of an open cluster, but has since become gravitationally unbound from the cluster.[101] Analyses in 2003 and 2005 found Sirius’s membership in the group to be questionable: the Ursa Major Group has an estimated age of 500 ± 100 million years, whereas Sirius, with metallicity similar to the Sun’s, has an age that is only half this, making it too young to belong to the group.[13][102][103] Sirius may instead be a member of the proposed Sirius Supercluster, along with other scattered stars such as Beta Aurigae, Alpha Coronae Borealis, Beta Crateris, Beta Eridani and Beta Serpentis.[104] This would be one of three large clusters located within 500 light-years (150 pc) of the Sun. The other two are the Hyades and the Pleiades, and each of these clusters consists of hundreds of stars.[105]

Distant star cluster[edit]

In 2017, a massive star cluster was discovered only 10 arcminutes from Sirius, making the two appear to be visually close to one other when viewed from the point of view of the Earth. It was discovered during a statistical analysis of Gaia data. The cluster is over a thousand times further away from us than the star system, but given its size it still appears at magnitude 8.3 .[106]

Etymology[edit]

The proper name «Sirius» comes from the Latin Sīrius, from the Ancient Greek Σείριος (Seirios, «glowing» or «scorcher»).[107] The Greek word itself may have been imported from elsewhere before the Archaic period,[108] one authority suggesting a link with the Egyptian god Osiris.[109] The name’s earliest recorded use dates from the 7th century BC in Hesiod’s poetic work Works and Days.[108] In 2016, the International Astronomical Union organized a Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)[110] to catalog and standardize proper names for stars. The WGSN’s first bulletin of July 2016[111] included a table of the first two batches of names approved by the WGSN, which included Sirius for the star α Canis Majoris A. It is now so entered in the IAU Catalog of Star Names.[112]

Sirius has over 50 other designations and names attached to it.[71] In Geoffrey Chaucer’s essay Treatise on the Astrolabe, it bears the name Alhabor and is depicted by a hound’s head. This name is widely used on medieval astrolabes from Western Europe.[20] In Sanskrit it is known as Mrgavyadha «deer hunter», or Lubdhaka «hunter». As Mrgavyadha, the star represents Rudra (Shiva).[113][114] The star is referred to as Makarajyoti in Malayalam and has religious significance to the pilgrim center Sabarimala.[115] In Scandinavia, the star has been known as Lokabrenna («burning done by Loki», or «Loki’s torch»).[116] In the astrology of the Middle Ages, Sirius was a Behenian fixed star,[117] associated with beryl and juniper. Its astrological symbol was listed by Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa.[118]

Cultural significance[edit]

Many cultures have historically attached special significance to Sirius, particularly in relation to dogs. It is often colloquially called the «Dog Star» as the brightest star of Canis Major, the «Great Dog» constellation. Canis Major was classically depicted as Orion’s dog. The Ancient Greeks thought that Sirius’s emanations could affect dogs adversely, making them behave abnormally during the «dog days», the hottest days of the summer. The Romans knew these days as dies caniculares, and the star Sirius was called Canicula, «little dog». The excessive panting of dogs in hot weather was thought to place them at risk of desiccation and disease. In extreme cases, a foaming dog might have rabies, which could infect and kill humans they had bitten.[31] Homer, in the Iliad, describes the approach of Achilles toward Troy in these words:[119]

Sirius rises late in the dark, liquid sky

On summer nights, star of stars,

Orion’s Dog they call it, brightest

Of all, but an evil portent, bringing heat

And fevers to suffering humanity.

In Iranian mythology, especially in Persian mythology and in Zoroastrianism, the ancient religion of Persia, Sirius appears as Tishtrya and is revered as the rain-maker divinity (Tishtar of New Persian poetry). Beside passages in the sacred texts of the Avesta, the Avestan language Tishtrya followed by the version Tir in Middle and New Persian is also depicted in the Persian epic Shahnameh of Ferdowsi. Because of the concept of the yazatas, powers which are «worthy of worship», Tishtrya is a divinity of rain and fertility and an antagonist of apaosha, the demon of drought. In this struggle, Tishtrya is depicted as a white horse.[120][121][122][123]

In Chinese astronomy Sirius is known as the star of the «celestial wolf» (Chinese and Japanese: 天狼 Chinese romanization: Tiānláng; Japanese romanization: Tenrō;[124] Korean and romanization: 천랑 /Cheonrang) in the Mansion of Jǐng (井宿). Many nations among the indigenous peoples of North America also associated Sirius with canines; the Seri and Tohono Oʼodham of the southwest note the star as a dog that follows mountain sheep, while the Blackfoot called it «Dog-face». The Cherokee paired Sirius with Antares as a dog-star guardian of either end of the «Path of Souls». The Pawnee of Nebraska had several associations; the Wolf (Skidi) tribe knew it as the «Wolf Star», while other branches knew it as the «Coyote Star». Further north, the Alaskan Inuit of the Bering Strait called it «Moon Dog».[125]

Several cultures also associated the star with a bow and arrows. The ancient Chinese visualized a large bow and arrow across the southern sky, formed by the constellations of Puppis and Canis Major. In this, the arrow tip is pointed at the wolf Sirius. A similar association is depicted at the Temple of Hathor in Dendera, where the goddess Satet has drawn her arrow at Hathor (Sirius). Known as «Tir», the star was portrayed as the arrow itself in later Persian culture.[126]

Sirius is mentioned in Surah, An-Najm («The Star»), of the Qur’an, where it is given the name الشِّعْرَى (transliteration: aš-ši’rā or ash-shira; the leader).[127] The verse is: «وأنَّهُ هُوَ رَبُّ الشِّعْرَى«, «That He is the Lord of Sirius (the Mighty Star).» (An-Najm:49)[128] Ibn Kathir said in his commentary «that it is the bright star, named Mirzam Al-Jawza’ (Sirius), which a group of Arabs used to worship».[129] The alternate name Aschere, used by Johann Bayer, is derived from this.[19]

Sirius midnight culmination at New Year 2022 local solar time[130]

In theosophy, it is believed the Seven Stars of the Pleiades transmit the spiritual energy of the Seven Rays from the Galactic Logos to the Seven Stars of the Great Bear, then to Sirius. From there is it sent via the Sun to the god of Earth (Sanat Kumara), and finally through the seven Masters of the Seven Rays to the human race.[131]

The midnight culmination of Sirius in the northern hemisphere coincides with the beginning of the New Year[130] of the Gregorian Calendar during the decades around the year 2000. Over the years, its midnight culmination moves slowly, owing to the combination of the star’s proper motion and the precession of the equinoxes. At the time of the introduction of the Gregorian calendar in the year 1582, its culmination occurred 17 minutes before midnight into the new year under the assumption of a constant motion. According to Richard Hinckley Allen[132] its mightnight culmination was celebrated at the Temple of Demeter at Eleusis.

Dogon[edit]

The Dogon people are an ethnic group in Mali, West Africa, reported by some researchers to have traditional astronomical knowledge about Sirius that would normally be considered impossible without the use of telescopes. According to Marcel Griaule, they knew about the fifty-year orbital period of Sirius and its companion prior to western astronomers.[133][134]

Doubts have been raised about the validity of Griaule and Dieterlein’s work.[135][136] In 1991, anthropologist Walter van Beek concluded about the Dogon, «Though they do speak about sigu tolo [which is what Griaule claimed the Dogon called Sirius] they disagree completely with each other as to which star is meant; for some it is an invisible star that should rise to announce the sigu [festival], for another it is Venus that, through a different position, appears as sigu tolo. All agree, however, that they learned about the star from Griaule.»[137] According to Noah Brosch cultural transfer of relatively modern astronomical information could have taken place in 1893, when a French expedition arrived in Central West Africa to observe the total eclipse on 16 April.[138]

Serer religion[edit]

In the religion of the Serer people of Senegal, the Gambia and Mauritania, Sirius is called Yoonir from the Serer language (and some of the Cangin language speakers, who are all ethnically Serers). The star Sirius is one of the most important and sacred stars in Serer religious cosmology and symbolism. The Serer high priests and priestesses (Saltigues, the hereditary «rain priests»[141]) chart Yoonir in order to forecast rainfall and enable Serer farmers to start planting seeds. In Serer religious cosmology, it is the symbol of the universe.[139][140]

Modern significance[edit]

The position of Sirius on a radar map among all stellar objects or stellar systems within 9 light years (ly) from the map’s center, the Sun (Sol). The diamond-shapes are their positions entered according to right ascension in hours angle (indicated at the edge of the map’s reference disc), and according to their declination. The second mark shows each’s distance from Sol, with the concentric circles indicating the distance in steps of one ly.

Sirius features on the coat of arms of Macquarie University, and is the name of its alumnae journal.[142] Seven ships of the Royal Navy have been called HMS Sirius since the 18th century, with the first being the flagship of the First Fleet to Australia in 1788.[143] The Royal Australian Navy subsequently named a vessel HMAS Sirius in honor of the flagship.[144] American vessels include the USNS Sirius (T-AFS-8) as well as a monoplane model—the Lockheed Sirius, the first of which was flown by Charles Lindbergh.[145] The name was also adopted by Mitsubishi Motors as the Mitsubishi Sirius engine in 1980.[146] The name of the North American satellite radio company CD Radio was changed to Sirius Satellite Radio in November 1999, being named after «the brightest star in the night sky».[147] Sirius is one of the 27 stars on the flag of Brazil, where it represents the state of Mato Grosso.[148]

Composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, who wrote a piece called Sirius, is claimed to have said on several occasions that he came from a planet in the Sirius system.[149][150] To Stockhausen, Sirius stood for «the place where music is the highest of vibrations» and where music had been developed in the most perfect way.[151]

Sirius has been the subject of poetry.[152] Dante and John Milton reference the star, and it is the «powerful western fallen star» of Walt Whitman’s «When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d», while Tennyson’s poem The Princess describes the star’s scintillation:

…the fiery Sirius alters hue

And bickers into red and emerald.[153]

See also[edit]

- List of stars in Canis Major

Notes[edit]

- ^

Compare the meaning of the Egyptian name with Sirius’s completion of the Winter Triangle asterism, joining the other two brightest stars of the northern winter sky, Betelgeuse and Procyon. - ^

As Sirius is visible together with the constellation of Orion, the Egyptians worshiped Orion as the god Sah, the husband of Sopdet, with whom she had a son, the sky god Sopdu. The goddess Sopdet was later syncretized with the goddess Isis, Sah was linked with Osiris, and Sopdu was linked with Horus. The joining of Sopdet with Isis would allow Plutarch to state that «The soul of Isis is called Dog by the Greeks», meaning Sirius worshiped as Isis-Sopdet by Egyptians was named the Dog by the Greeks and Romans. The 70 day period of the absence of Sirius from the sky was understood as the passing of Sopdet-Isis and Sah-Osiris through the Egyptian underworld.[29] - ^

Two full 50.09 year orbits following the periastron epoch of 1894.13 gives a date of 1994.31. - ^

Two and one-half 50.09 year orbits following the periastron epoch of 1894.13 gives a date of 2019.34 . - ^

Semi-major axis in AU = semimajor axis in seconds / parallax = 7.56″ / 0.37921 = 19.8 AU; as the eccentricity is 0.6, the distance fluctuates between 40% and 160% of that, roughly from 8 AU to 32 AU.

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ «Sirius». Dictionary.com Unabridged (v 1.1). Random House, Inc. Retrieved 6 April 2008.

- ^ a b Fabricius, C.; Høg, E.; Makarov, V.V.; Mason, B.D.; Wycoff, G.L.; Urban, S.E. (2002). «The Tycho double star catalogue». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 384: 180–189. Bibcode:2002A&A…384..180F. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20011822.

- ^ a b c Hoffleit, D.; Warren, W. H. Jr. (1991). «Entry for HR 2491». Bright Star Catalogue (5th Revised Ed. (Preliminary Version) ed.). CDS. Bibcode:1991bsc..book…..H.

- ^ a b Gianninas, A.; Bergeron, P.; Ruiz, M.T. (2011). «A spectroscopic survey and analysis of bright, hydrogen-rich white dwarfs». The Astrophysical Journal. 743 (2): 138. arXiv:1109.3171. Bibcode:2011ApJ…743..138G. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/743/2/138. S2CID 119210906.

- ^ a b Holberg, J.B.; Oswalt, T.D.; Sion, E.M.; Barstow, M.A.; Burleigh, M.R. (2013). «Where are all the Sirius-like binary systems?». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 435 (3): 2077–2091. arXiv:1307.8047. Bibcode:2013MNRAS.435.2077H. doi:10.1093/mnras/stt1433. S2CID 54551449.

- ^ a b Gray, R.O.; Corbally, C.J.; Garrison, R.F.; McFadden, M.T.; Robinson, P.E. (2003). «Contributions to the Nearby Stars (NStars) Project: Spectroscopy of stars earlier than M0 within 40 parsecs: The Northern Sample. I». Astronomical Journal. 126 (4): 2048–2059. arXiv:astro-ph/0308182. Bibcode:2003AJ….126.2048G. doi:10.1086/378365. S2CID 119417105.

- ^ a b c McCook, G. P.; Sion, E. M. (2014). «Entry for WD 0642-166». A Catalogue of Spectroscopically Identified White Dwarfs. VizieR Online Data Catalog. CDS. Bibcode:2016yCat….102035M.

- ^ Gontcharov, G.A. (2006). «Pulkovo Compilation of Radial Velocities for 35 495 Hipparcos stars in a common system». Astronomy Letters. 32 (11): 759–771. arXiv:1606.08053. Bibcode:2006AstL…32..759G. doi:10.1134/S1063773706110065. ISSN 1063-7737. S2CID 119231169.

- ^ a b c van Leeuwen, F. (November 2007). «Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 474 (2): 653–664. arXiv:0708.1752. Bibcode:2007A&A…474..653V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357. S2CID 18759600.

- ^ Malkov, O. Yu. (December 2007). «Mass-luminosity relation of intermediate-mass stars». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 382 (3): 1073–1086. Bibcode:2007MNRAS.382.1073M. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2007.12086.x.

- ^ a b c Vallenari, A.; et al. (Gaia Collaboration) (2022). «Gaia Data Release 3. Summary of the content and survey properties». Astronomy & Astrophysics. arXiv:2208.00211. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202243940. Gaia DR3 record for this source at VizieR.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bond, Howard E.; Schaefer, Gail H.; Gilliland, Ronald L.; Holberg, Jay B.; Mason, Brian D.; Lindenblad, Irving W.; et al. (2017). «The Sirius system and its astrophysical puzzles: Hubble Space Telescope and ground-based astrometry». The Astrophysical Journal. 840 (2): 70. arXiv:1703.10625. Bibcode:2017ApJ…840…70B. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/aa6af8. S2CID 51839102.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Liebert, James; Young, P. A.; Arnett, David; Holberg, J. B.; Williams, Kurtis A. (2005). «The Age and Progenitor Mass of Sirius B». The Astrophysical Journal. 630 (1): L69–L72. arXiv:astro-ph/0507523. Bibcode:2005ApJ…630L..69L. doi:10.1086/462419. S2CID 8792889.

- ^ a b c Adelman, Saul J. (8–13 July 2004). «The Physical Properties of normal A stars». Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union. Vol. 2004. Poprad, Slovakia: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–11. Bibcode:2004IAUS..224….1A. doi:10.1017/S1743921304004314.

- ^ a b Qiu, H. M.; Zhao, G.; Chen, Y. Q.; Li, Z. W. (2001). «The Abundance Patterns of Sirius and Vega». The Astrophysical Journal. 548 (2): 953–965. Bibcode:2001ApJ…548..953Q. doi:10.1086/319000.

- ^ a b Royer, F.; Gerbaldi, M.; Faraggiana, R.; Gómez, A. E. (2002). «Rotational velocities of A-type stars. I. Measurement of v sin i in the southern hemisphere». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 381 (1): 105–121. arXiv:astro-ph/0110490. Bibcode:2002A&A…381..105R. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20011422. S2CID 13133418.

- ^ a b Holberg, J. B.; Barstow, M. A.; Bruhweiler, F. C.; Cruise, A. M.; Penny, A. J. (1998). «Sirius B: A New, More Accurate View». The Astrophysical Journal. 497 (2): 935–942. Bibcode:1998ApJ…497..935H. doi:10.1086/305489.

- ^ Sweeney, M.A. (1976). «Cooling times, luminosity functions and progenitor masses of degenerate dwarfs». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 49: 375–385. Bibcode:1976A&A….49..375S.

- ^ a b c Hinckley, Richard Allen (1899). Star-names and Their Meanings. New York: G. E. Stechert. pp. 117–129.

- ^ a b Gingerich, O. (1987). «Zoomorphic astrolabes and the introduction of Arabic star names into Europe». Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 500 (1): 89–104. Bibcode:1987NYASA.500…89G. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb37197.x. S2CID 84102853.

- ^ Singh, Nagendra Kumar (2002). Encyclopaedia of Hinduism, A Continuing Series. Anmol Publications PVT. LTD. p. 794. ISBN 81-7488-168-9.

- ^ Spahn, Mark; Hadamitzky, Wolfgang; Fujie-Winter, Kimiko (1996). The Kanji dictionary. Tuttle language library. Tuttle Publishing. p. 724. ISBN 0-8048-2058-9.

- ^ «Sirius A». SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 20 October 2007.

- ^ «Sirius B». SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 23 October 2007.

- ^ Schaaf, Fred (2008). The Brightest Stars. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-471-70410-2.

- ^ Sirius is a future southern Pole Star. 2023-02-11.

- ^ Tomkin, Jocelyn (April 1998). «Once and future celestial kings». Sky and Telescope. 95 (4): 59–63. Bibcode:1998S&T….95d..59T.

- ^ a b Wendorf, Fred; Schild, Romuald (2001). Holocene Settlement of the Egyptian Sahara: Volume 1, The Archaeology of Nabta Plain (Google Book Search preview). Springer. p. 500. ISBN 0-306-46612-0.

- ^ Holberg 2007, pp. 4–5

- ^ Holberg 2007, p. 19

- ^ a b c Holberg 2007, p. 20

- ^ Holberg 2007, pp. 16–17

- ^ Ovid. Fasti IV, lines 901–942.

- ^ Holberg 2007, p. 25

- ^ Holberg 2007, pp. 25–26

- ^ Henry, Teuira (1907). «Tahitian Astronomy: Birth of Heavenly Bodies». The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 16 (2): 101–04. JSTOR 20700813.

- ^ Aitken, R. G. (1942). «Edmund Halley and Stellar Proper Motions». Astronomical Society of the Pacific Leaflets. 4 (164): 103–112. Bibcode:1942ASPL….4..103A.

- ^ Holberg 2007, pp. 41–42

- ^ Daintith, John; Mitchell, Sarah; Tootill, Elizabeth; Gjertsen, D. (1994). Biographical Encyclopedia of Scientists. CRC Press. p. 442. ISBN 0-7503-0287-9.

- ^ Huggins, W. (1868). «Further observations on the spectra of some of the stars and nebulae, with an attempt to determine therefrom whether these bodies are moving towards or from the Earth, also observations on the spectra of the Sun and of Comet II». Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 158: 529–564. Bibcode:1868RSPT..158..529H. doi:10.1098/rstl.1868.0022.

- ^ Hearnshaw, John B. (17 March 2014). The Analysis of Starlight: Two centuries of astronomical spectroscopy. Cambridge University Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-107-03174-6.

- ^ Huygens, C. (1698). ΚΟΣΜΟΘΕΩΡΟΣ, sive De terris cœlestibus earumque ornatu conjecturae (in Latin). The Hague: Apud A. Moetjens, bibliopolam. p. 137.

- ^ Maskelyne, N. (1759). «LXXVIII. A proposal for discovering the annual parallax of Sirius». Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 51: 889–895. Bibcode:1759RSPT…51..889M. doi:10.1098/rstl.1759.0080.

- ^ Henderson, T. (1840). «On the parallax of Sirius». Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society. 11: 239–248. Bibcode:1840MmRAS..11..239H.

- ^ Henderson, T. (1839). «On the parallax of Sirius». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 5 (2): 5–7. Bibcode:1839MNRAS…5….5H. doi:10.1093/mnras/5.2.5.

- ^ Holberg 2007, p. 45

- ^ Bessel, F. W. (December 1844). «On the Variations of the Proper Motions of Procyon and Sirius«. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 6 (11): 136–141. Bibcode:1844MNRAS…6R.136B. doi:10.1093/mnras/6.11.136a.

- ^ Flammarion, Camille (August 1877). «The Companion of Sirius». The Astronomical Register. 15 (176): 186–189. Bibcode:1877AReg…15..186F.

- ^ Craig, John; Gravatt, William; Slater, Thomas; Rennie, George. «The Craig Telescope». craig-telescope.co.uk. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ^ Appletons’ annual cyclopaedia and register of important events of the year: 1862. New York: D. Appleton & Company. 1863. p. 176.

- ^ a b Benest, D.; Duvent, J. L. (July 1995). «Is Sirius a triple star?». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 299: 621–628. Bibcode:1995A&A…299..621B. – For the instability of an orbit around Sirius B, see § 3.2.

- ^ Bonnet-Bidaud, J. M.; Pantin, E. (October 2008). «ADONIS high contrast infrared imaging of Sirius-B». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 489 (2): 651–655. arXiv:0809.4871. Bibcode:2008A&A…489..651B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078937. S2CID 14743554.

- ^ Adams, W. S. (December 1915). «The Spectrum of the Companion of Sirius». Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 27 (161): 236–237. Bibcode:1915PASP…27..236A. doi:10.1086/122440.

- ^ Holberg, J. B. (2005). «How Degenerate Stars Came to be Known as White Dwarfs». Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 37 (2): 1503. Bibcode:2005AAS…20720501H.

- ^ Hanbury Brown, R.; Twiss, R. Q. (1958). «Interferometry of the Intensity Fluctuations in Light. IV. A Test of an Intensity Interferometer on Sirius A». Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 248 (1253): 222–237. Bibcode:1958RSPSA.248..222B. doi:10.1098/rspa.1958.0240. S2CID 124546373.

- ^ a b Barstow, M. A.; Bond, Howard E.; Holberg, J. B.; Burleigh, M. R.; Hubeny, I.; Koester, D. (2005). «Hubble Space Telescope spectroscopy of the Balmer lines in Sirius B». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 362 (4): 1134–1142. arXiv:astro-ph/0506600. Bibcode:2005MNRAS.362.1134B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2005.09359.x. S2CID 4607496.

- ^ a b Holberg 2007, p. 157

- ^ Holberg 2007, p. 32

- ^ Ceragioli, R. C. (1995). «The Debate Concerning ‘Red’ Sirius». Journal for the History of Astronomy. 26 (3): 187–226. Bibcode:1995JHA….26..187C. doi:10.1177/002182869502600301. S2CID 117111146.

- ^ Holberg 2007, p. 158

- ^ Holberg 2007, p. 161

- ^ Holberg 2007, p. 162

- ^ a b c Whittet, D. C. B. (1999). «A physical interpretation of the ‘red Sirius’ anomaly». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 310 (2): 355–359. Bibcode:1999MNRAS.310..355W. doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.1999.02975.x.

- ^ Holberg 2007, p. 163

- ^ 江晓原 (1992). 中国古籍中天狼星颜色之记载. 天文学报 (in Chinese). 33 (4).

- ^ Jiang, Xiao-Yuan (April 1993). «The colour of Sirius as recorded in ancient Chinese texts». Chinese Astronomy and Astrophysics. 17 (2): 223–228. Bibcode:1993ChA&A..17..223J. doi:10.1016/0275-1062(93)90073-X.

- ^ Schlosser, W.; Bergmann, W. (November 1985). «An early-medieval account on the red colour of Sirius and its astrophysical implications». Nature. 318 (6041): 45–46. Bibcode:1985Natur.318…45S. doi:10.1038/318045a0. S2CID 4323130.

- ^ McCluskey, S. C. (January 1987). «The colour of Sirius in the sixth century». Nature. 318 (325): 87. Bibcode:1987Natur.325…87M. doi:10.1038/325087a0. S2CID 5297220.

- ^ van Gent, R. H. (January 1987). «The colour of Sirius in the sixth century». Nature. 318 (325): 87–89. Bibcode:1987Natur.325…87V. doi:10.1038/325087b0. S2CID 186243165.

- ^ Kuchner, Marc J.; Brown, Michael E. (2000). «A Search for Exozodiacal Dust and Faint Companions Near Sirius, Procyon, and Altair with the NICMOS Coronagraph». Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 112 (772): 827–832. arXiv:astro-ph/0002043. Bibcode:2000PASP..112..827K. doi:10.1086/316581. S2CID 18971656.

- ^ a b Holberg 2007, p. xi

- ^ Espenak, Fred. «Mars Ephemeris». Twelve Year Planetary Ephemeris: 1995–2006, NASA Reference Publication 1349. Archived from the original on 17 February 2013.

- ^ Holberg 2007, p. 82

- ^ «Stories from the Stars». Stargazers Astronomy Shop. 2000. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- ^ Darling, David. «Winter Triangle». The Internet Encyclopedia of Science. Retrieved 20 October 2007.

- ^ Henshaw, C. (1984). «On the Visibility of Sirius in Daylight». Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 94 (5): 221–222. Bibcode:1984JBAA…94..221H.

- ^ Mullaney, James (March 2008). «Orion’s Splendid Double Stars: Pretty Doubles in Orion’s Vicinity». Sky & Telescope. Retrieved 1 February 2008.

- ^ Sordiglioni, Gianluca (2016). «06451-1643 AGC 1AB (Sirio)». Double Star Database. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ Henry, Todd J. (1 July 2006). «The One Hundred Nearest Star Systems». RECONS. Archived from the original on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2006.

- ^ «The Brightest Stars». Royal Astronomical Society of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2007.

- ^ a b c «Sirius 2». SolStation. Retrieved 4 August 2006.

- ^ Angrum, Andrea (25 August 2005). «Interstellar Mission». NASA/JPL. Retrieved 7 May 2007.

- ^ a b Holberg 2007, p. 214

- ^ Backman, D. E. (30 June – 11 July 1986). «IRAS observations of nearby main sequence stars and modeling of excess infrared emission». In Gillett, F. C.; Low, F. J. (eds.). Proceedings, 6th Topical Meetings and Workshop on Cosmic Dust and Space Debris. Vol. 6. Toulouse, France: COSPAR and IAF. pp. 43–46. Bibcode:1986AdSpR…6…43B. doi:10.1016/0273-1177(86)90209-7. ISSN 0273-1177.

- ^ Brosch 2008, p. 126

- ^ Vigan, A.; Gry, C.; Salter, G.; Mesa, D.; Homeier, D.; Moutou, C.; Allard, F. (2015). «High-contrast imaging of Sirius A with VLT/SPHERE: looking for giant planets down to one astronomical unit». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 454 (1): 129–143. arXiv:1509.00015. Bibcode:2015MNRAS.454..129V. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv1928. S2CID 119260068.

- ^ Lucas, Miles; Bottom, Michael; Ruane, Garreth; Ragland, Sam (2022). «An imaging search for post-main-sequence planets of Sirius B». The Astronomical Journal. 163 (2): 81. arXiv:2112.05234. Bibcode:2022AJ….163…81L. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/ac4032. S2CID 245117921.

- ^ Bragança, Pedro (15 July 2003). «The 10 Brightest Stars». SPACE.com. Archived from the original on 16 June 2009. Retrieved 4 August 2006.

- ^ a b c d Kervella, P.; Thevenin, F.; Morel, P.; Borde, P.; Di Folco, E. (2003). «The interferometric diameter and internal structure of Sirius A». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 407 (2): 681–688. arXiv:astro-ph/0306604. Bibcode:2003A&A…408..681K. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20030994. S2CID 16678626.

- ^ Aufdenberg, J.P.; Ridgway, S.T.; et al. (2006). «First results from the CHARA Array: VII. Long-Baseline Interferometric Measurements of Vega Consistent with a Pole-On, Rapidly Rotating Star?» (PDF). Astrophysical Journal. 645 (1): 664–675. arXiv:astro-ph/0603327. Bibcode:2006ApJ…645..664A. doi:10.1086/504149. S2CID 13501650. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 July 2007. Retrieved 9 November 2007.

- ^ Petit, P.; et al. (August 2011). «Detection of a weak surface magnetic field on Sirius A: are all tepid stars magnetic?». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 532: L13. arXiv:1106.5363. Bibcode:2011A&A…532L..13P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201117573. S2CID 119106028.

- ^ Stellar mass and lifetime on the main sequence. NASA’s cosmos (diagram). Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ Brosch 2008, p. 198.

- ^ Aurière, M.; et al. (November 2010). «No detection of large-scale magnetic fields at the surfaces of Am and HgMn stars». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 523: A40. arXiv:1008.3086. Bibcode:2010A&A…523A..40A. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201014848. S2CID 118643022.

- ^ Imamura, James N. (2 October 1995). «Cooling of White Dwarfs». University of Oregon. Archived from the original on 15 December 2006. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- ^ Siess, Lionel (2000). «Computation of Isochrones». Institut d’Astronomie et d’Astrophysique, Université libre de Bruxelles. Retrieved 24 March 2007.

- ^ Palla, Francesco (16–20 May 2005). «Stellar evolution before the ZAMS». Proceedings of the international Astronomical Union 227. Italy: Cambridge University Press. pp. 196–205. Bibcode:1976IAUS…73…75P.

- ^ Koester, D.; Chanmugam, G. (1990). «Physics of white dwarf stars». Reports on Progress in Physics. 53 (7): 837–915. Bibcode:1990RPPh…53..837K. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/53/7/001. S2CID 250915046.

- ^ Holberg, J. B.; Barstow, M. A.; Burleigh, M. R.; Kruk, J. W.; Hubeny, I.; Koester, D. (2004). «FUSE observations of Sirius B». Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 36: 1514. Bibcode:2004AAS…20510303H.

- ^ Andrew, le Page (6 April 2017). «New Hubble observations of the Sirius system». drewexmachina.com. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ^ Frommert, Hartmut; Kronberg, Christine (26 April 2003). «The Ursa Major Moving Cluster, Collinder 285». SEDS. Archived from the original on 20 December 2007. Retrieved 22 November 2007.

- ^ King, Jeremy R.; Villarreal, Adam R.; Soderblom, David R.; Gulliver, Austin F.; Adelman, Saul J. (2003). «Stellar Kinematic Groups. II. A Reexamination of the Membership, Activity, and Age of the Ursa Major Group». Astronomical Journal. 125 (4): 1980–2017. Bibcode:2003AJ….125.1980K. doi:10.1086/368241.

- ^ Croswell, Ken (27 July 2005). «The life and times of Sirius B». astronomy.com. Retrieved 19 October 2007.

- ^ Eggen, Olin J. (1992). «The Sirius supercluster in the FK5». Astronomical Journal. 104 (4): 1493–1504. Bibcode:1992AJ….104.1493E. doi:10.1086/116334.

- ^ Olano, C. A. (2001). «The Origin of the Local System of Gas and Stars». The Astronomical Journal. 121 (1): 295–308. Bibcode:2001AJ….121..295O. doi:10.1086/318011. S2CID 120137433.

- ^ Koposov, Sergey E.; Belokurov, V.; Torrealba, G. (2017). «Gaia 1 and 2. A pair of new galactic star clusters». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 470 (3): 2702–2709. arXiv:1702.01122. Bibcode:2017MNRAS.470.2702K. doi:10.1093/mnras/stx1182. S2CID 119095351.

- ^ Liddell, Henry G.; Scott, Robert (1980). Greek-English Lexicon (Abridged ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-910207-4.

- ^ a b Holberg 2007, pp. 15–16

- ^ Brosch 2008, p. 21

- ^ «IAU Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)». Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ «Bulletin of the IAU Working Group on Star Names» (PDF). No. 1. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ^ «IAU Catalog of Star Names» (plain text). Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ^ Kak, Subhash. «Indic ideas in the Greco-Roman world». IndiaStar Review of Books. Archived from the original on 29 July 2010. Retrieved 23 July 2010.

- ^ «Shri Shri Shiva Mahadeva». Archived from the original on 4 July 2013.

- ^ «Makarajyothi is a star: senior Thantri». The Hindu. 24 January 2011. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- ^ Rydberg, Viktor (1889). Rasmus Björn Anderson (ed.). Teutonic mythology. Vol. 1. S. Sonnenschein & co.

- ^ Tyson, Donald; Freake, James (1993). Three Books of Occult Philosophy. Llewellyn Worldwide. ISBN 0-87542-832-0.

- ^ Agrippa, Heinrich Cornelius (1533). De Occulta Philosophia. ISBN 90-04-09421-0.

- ^ Homer (1997). Iliad. Trans. Stanley Lombardo. Indianapolis: Hackett. ISBN 978-0-87220-352-5. 22.33–37.

- ^ Doostkhah, Jalil (1996). Avesta. Kohantarin Sorōdhāye Irāniān. Tehran: Morvarid Publications. ISBN 964-6026-17-6.

- ^ West, E. W. (1895–1910). Pahlavi Texts. Routledge Curzon, 2004. ISBN 0-7007-1544-4.

- ^ Razi, Hashem (2002). Encyclopaedia of Ancient Iran. Tehran: Sokhan Publications. ISBN 964-372-027-6.

- ^ Ferdowsi, A. Shahnameh e Ferdowsi. Bank Melli Iran Publications, 2003. ISBN 964-93135-3-2.

- ^ Holberg 2007, p. 22

- ^ Holberg 2007, p. 23

- ^ Holberg 2007, p. 24

- ^ Staff (2007). «Sirius». Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Retrieved 10 September 2007.

- ^ «An-Najm (The Star), Surah 53». Translations of the Qur’an. University of Southern California, Center for Muslim-Jewish Engagement. 2007. Archived from the original on 19 February 2009. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- ^ «Tafsir Ibn Kathir». 9 July 2012. Archived from the original on 21 January 2013. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ^ a b «Sirius midnight culmination New Years Eve». 31 December 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ Baker, Douglas (1977). The Seven Rays: Key to the Mysteries. Wellingborough, Herts.: Aquarian Press. ISBN 0-87728-377-X.

- ^ Allen, Richard Hinckley (1899). Star-names and Their Meanings. G.E. Stechert. p. 125.

The culmination of this star at midnight was celebrated in the great temple of Ceres at Eleusis

- ^ Griaule, Marcel (1965). Conversations with Ogotemmeli: An Introduction to Dogon Religious Ideas. ISBN 0-19-519821-2. (many reprints) Originally published in 1948 as Dieu d’Eau.

- ^ Griaule, Marcel; Dieterlen, Germaine (1965). The Pale Fox. Institut d’Ethnologie. Originally published as Le Renard Pâle.

- ^ Bernard R. Ortiz de Montellano. «The Dogon Revisited». Archived from the original on 16 February 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- ^ Philip Coppens. «Dogon Shame». Archived from the original on 27 December 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- ^ van Beek, W. A. E.; Bedaux; Blier; Bouju; Crawford; Douglas; Lane; Meillassoux (1991). «Dogon Restudied: A Field Evaluation of the Work of Marcel Griaule». Current Anthropology. 32 (2): 139–167. doi:10.1086/203932. JSTOR 2743641. S2CID 224796672.

- ^ Brosch 2008, p. 65

- ^ a b Gravrand, Henry, «La civilisation sereer : Pangool«, vol. 2, Les Nouvelles Editions Africaines du Sénégal, (1990) pp. 20–21, 149–155, ISBN 2-7236-1055-1.

- ^ a b Clémentine Faïk-Nzuji Madiya, Canadian Museum of Civilization, Canadian Centre for Folk Culture Studies, International Centre for African Language, Literature and Tradition (Louvain, Belgium). ISBN 0-660-15965-1. pp. 5, 27, 115.

- ^ Galvan, Dennis Charles, The State Must be our Master of Fire : How Peasants Craft Culturally Sustainable Development in Senegal, Berkeley, University of California Press, (2004), pp. 86–135, ISBN 978-0-520-23591-5.

- ^ «About Macquarie University — Naming of the University». Macquarie University official website. Macquarie University. 2007. Retrieved 27 December 2007.

- ^ Henderson G, Stanbury M (1988). The Sirius:Past and Present. Sydney: Collins. p. 38. ISBN 0-7322-2447-0.

- ^ Royal Australian Navy (2006). «HMAS Sirius:Welcome Aboard». Royal Australian Navy — Official Site. Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- ^ «Lockheed Sirius «Tingmissartoq», Charles A. Lindbergh». Smithsonian : National Air and Space Museum. Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ «Mitsubishi Motors history». Mitsubishi Motors – South Africa Official Website. Mercedes Benz. 2007. Archived from the original on 30 December 2007. Retrieved 27 January 2008.

- ^ «Sirius Satellite Radio, Inc. – Company Profile, Information, Business Description, History, Background Information on Sirius Satellite Radio, Inc». Net Industries, LLC. Retrieved 22 January 2008.

- ^ Duarte, Paulo Araújo. «Astronomia na Bandeira Brasileira». Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina. Archived from the original on 2 May 2008. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- ^ McEnery, Paul (16 January 2001). «Karlheinz Stockhausen». Salon.com. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012.

- ^ Tom Service (13 October 2005). «Beam Me up, Stocky». The Guardian.

- ^ Michael Kurtz, Stockhausen. Eine Biografie. Kassel, Bärenreiter Verlag, 1988: p. 271.

- ^ Brosch 2008, p. 33

- ^ Allen, Richard Hinckley (1899). Star-names and their meanings. New York: G.E. Stechert. pp. 117–131.

Bibliography[edit]

- Brosch, Noah (2008). Sirius Matters. Astrophysics and Space Science Library. Vol. 354. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-8319-8_10. ISBN 978-1-4020-8318-1.

- Holberg, J.B. (2007). Sirius: Brightest Diamond in the Night Sky. Chichester, UK: Praxis Publishing. ISBN 978-0-387-48941-4.

- Makemson, Maud Worcester (1941). The Morning Star Rises: An Account of Polynesian Astronomy. Yale University Press. Bibcode:1941msra.book…..M.

External links[edit]

Look up dog days in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sirius.

- NASA Astronomy Picture of the Day: Sirius B in x-ray (6 October 2000)

- «Sirius Matters: Alien Contact». Chandra X-ray Center. 28 November 2000. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- Sankey, John. «Getting Sirius About Time». www.johnsankey.ca. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- Barker, Tho.; Stukeley, W. (1760). «Remarks on the Mutations of the Stars». Philosophical Transactions. 51: 498–504. doi:10.1098/rstl.1759.0049. JSTOR 105393.

Звезда Сириус один из самых ярких объектов земного ночного неба. Он манил человечество на протяжении всех истории, с ним связанно множество мифов и легенд разных народов, которых намного больше, чем современных научных сведений об этой звёздноё системе.

Содержание страницы

- 1 Физические характеристики и орбита

- 2 Система нескольких звезд

- 2.1 Сириус а

- 2.2 Сириус в

- 3 Расстояния до Сириуса

- 4 Интересные факты

- 5 Звезда Сириус в культуре

- 6 Сравнения, отличия Солнце и Сириуса

- 7 Научные гипотезы

- 8 Как найти звезду Сириус на ночном небе

- 9 В каком созвездии находится Сириус

- 9.1 Так же может заинтересовать

Физические характеристики и орбита

Угловое расстояние Сириуса составляет 106 градусов. Эта звезда такая яркая, потому что находится близко к нам, расстояние всего 8.6 световых лет. Температура звезды составляет в среднем 9940 Кальвинов. В разных слоях эта температура отличается. Светимость Сириуса составляет 25,4 L (светимостей солнца), что равняется 97.2 *10 в 26 степени Вт.

Радиус Сириуса равен 11.84 умноженная на 10 в 6 степени. Масса составляет 3. 96 умноженное на 10 в 30 степени кг., это примерно в 2 раза больше, чем радиус Солнца. Скорость вращения звезды равняется 16,7 км/с.

| Масса звезды | ~2 M⊙ |

| Радиус | 1,7 R⊙ |

| Температура звезды | 9940 K |

| Светимость | 25,4 L⊙ |

| Металличность | 0,5 |

| Вращение | 16,7 км/с |

| Период обращения | 50 лет |

| Наклонение | 136,5°v |

| Большая полуось | 7,56″ |

| Эксцентриситет | 0,592 |

Система нескольких звезд

Сириус – одна из самых ярких звёзд на небе, её изучали астрономы с глубокой древности, но только 31 января 1862 года астроном и оптик Альван Кларк при тестировании своего нового телескопа обнаружил, что у Сириуса есть спутник. Это открытие значимо ещё и потому, что Сириус В оказался белым карликом. До этого момента существование белых карликов не было подтверждено научно, это была теоретическая выкладка, как предположение возможного варианта старения нашего солнца и других подобных ему светил.

Звёздная система Сириус состоит из двух звёзд, вращающихся вокруг общего центра массы, совершая полный оборот за 50 лет.

Сириус а

Звезда звезды спектрального класса A1. Именно она составляет основу видимого светового спектра. Сириус А останется в прежнем состоянии около 660 миллионов лет, затем станет красным гигантов, и, в конце своей жизни станет Белым карликом как звезда Сириус В.

Сириус в

Белый карлик – умирающая звезда. излучение его очень яркое, но находится в инфорокрасном спектре, невидимом человеческому глазу. Она стала таковой предположительно 120 миллионов лет назад, пройдя стадию основной последовательности и красного гиганта. По подсчётам исследователей, в расцвете сил масса составляла около 5 солнечных масс.

Расстояния до Сириуса

Звезда Сириус – самая яркая в Северном полушарии. Но это обусловлено не огромными размерами, а близким расположением к Солнечной системе. Расстояние от нас всего 8.6 световых лет или 2.6 парсеков. По Удалённости звёздная система находится на 7 месте не считая Солнце после Лаланд 21185. А ближе всего к Земле находится звёздная система Центавра.

Интересные факты