Химический элемент — это определённый вид атомов.

Атомы разных химических элементов отличаются массой, размерами, строением и свойствами.

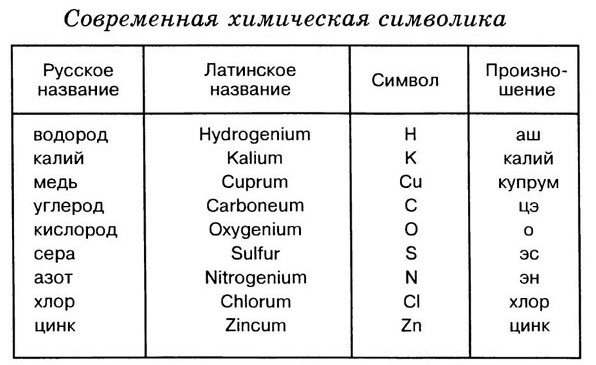

Каждый химический элемент имеет название и обозначается символом или химическим знаком.

Символ химического элемента состоит из одной или двух букв. Как правило, используются первые буквы его латинского названия.

|

Название элемента |

Символ | Произношение |

| Азот |

N |

«эн» |

| Алюминий |

Al |

«алюминий» |

| Барий |

Ba |

«барий» |

| Бром |

Br |

«бром» |

| Водород |

H |

«аш» |

| Гелий |

He |

«гелий» |

| Железо |

Fe |

«феррум» |

| Золото |

Au |

«аурум» |

| Иод |

I |

«иод» |

| Калий |

K |

«калий» |

| Кальций |

Ca |

«кальций» |

| Кислород |

O |

«о» |

| Кремний |

Si |

«силициум» |

| Магний |

Mg |

«магний» |

| Медь |

Cu |

«купрум» |

| Натрий |

Na |

«натрий» |

| Сера |

S |

«эс» |

| Серебро |

Ag |

«аргентум» |

| Углерод |

C |

«це» |

| Фосфор |

P |

«пэ» |

| Фтор |

F |

«фтор» |

| Хлор |

Cl |

«хлор» |

| Цинк |

Zn |

«цинк» |

Названия и символы (118) химических элементов приведены в периодической таблице. Более (20) элементов получены искусственно с помощью сложных физических методов. Таблица постоянно дополняется новыми элементами.

Атомы химических элементов соединяются друг с другом в разных комбинациях и образуют огромное количество природных и синтетических веществ.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Chemical symbols are the abbreviations used in chemistry for chemical elements, functional groups and chemical compounds. Element symbols for chemical elements normally consist of one or two letters from the Latin alphabet and are written with the first letter capitalised.

History[edit]

Earlier symbols for chemical elements stem from classical Latin and Greek vocabulary. For some elements, this is because the material was known in ancient times, while for others, the name is a more recent invention. For example, Pb is the symbol for lead (plumbum in Latin); Hg is the symbol for mercury (hydrargyrum in Greek); and He is the symbol for helium (a Neo-Latin name) because helium was not known in ancient Roman times. Some symbols come from other sources, like W for tungsten (Wolfram in German) which was not known in Roman times.

A three-letter temporary symbol may be assigned to a newly synthesized (or not yet synthesized) element. For example, «Uno» was the temporary symbol for hassium (element 108) which had the temporary name of unniloctium, based on the digits of its atomic number. There are also some historical symbols that are no longer officially used.

Extension of the symbol[edit]

Annotated example of an atomic symbol

In addition to the letters for the element itself, additional details may be added to the symbol as superscripts or subscripts a particular isotope, ionization, or oxidation state, or other atomic detail.[1] A few isotopes have their own specific symbols rather than just an isotopic detail added to their element symbol.

Attached subscripts or superscripts specifying a nuclide or molecule have the following meanings and positions:

- The nucleon number (mass number) is shown in the left superscript position (e.g., 14N). This number defines the specific isotope. Various letters, such as «m» and «f» may also be used here to indicate a nuclear isomer (e.g., 99mTc). Alternately, the number here can represent a specific spin state (e.g., 1O2). These details can be omitted if not relevant in a certain context.

- The proton number (atomic number) may be indicated in the left subscript position (e.g., 64Gd). The atomic number is redundant to the chemical element, but is sometimes used to emphasize the change of numbers of nucleons in a nuclear reaction.

- If necessary, a state of ionization or an excited state may be indicated in the right superscript position (e.g., state of ionization Ca2+).

- The number of atoms of an element in a molecule or chemical compound is shown in the right subscript position (e.g., N2 or Fe2O3). If this number is one, it is normally omitted — the number one is implicitly understood if unspecified.

- A radical is indicated by a dot on the right side (e.g., Cl• for a neutral chlorine atom). This is often omitted unless relevant to a certain context because it is already deducible from the charge and atomic number, as generally true for nonbonded valence electrons in skeletal structures.

Many functional groups also have their own chemical symbol, e.g. Ph for the phenyl group, and Me for the methyl group.

A list of current, dated, as well as proposed and historical signs and symbols is included here with its signification. Also given is each element’s atomic number, atomic weight, or the atomic mass of the most stable isotope, group and period numbers on the periodic table, and etymology of the symbol.

Symbols for chemical elements[edit]

| List of chemical elements | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Z | Symbol | Name | Origin of name[2][3] |

| 1 | H | Hydrogen | Greek elements hydro- and -gen, meaning ‘water-forming’ |

| 2 | He | Helium | Greek hḗlios, ‘sun’ |

| 3 | Li | Lithium | Greek líthos, ‘stone’ |

| 4 | Be | Beryllium | beryl, a mineral (ultimately from the name of Belur in southern India) |

| 5 | B | Boron | borax, a mineral (from Arabic bawraq) |

| 6 | C | Carbon | Latin carbo, ‘coal’ |

| 7 | N | Nitrogen | Greek nítron and -gen, meaning ‘niter-forming’ |

| 8 | O | Oxygen | Greek oxy- and -gen, meaning ‘acid-forming’ |

| 9 | F | Fluorine | Latin fluere, ‘to flow’ |

| 10 | Ne | Neon | Greek néon, ‘new’ |

| 11 | Na | Sodium | English soda (the symbol Na is derived from Neo-Latin natrium, coined from German Natron, ‘natron’) |

| 12 | Mg | Magnesium | Magnesia, a district of Eastern Thessaly in Greece |

| 13 | Al | Aluminium | alumina, from Latin alumen (gen. alumni), ‘bitter salt, alum’ |

| 14 | Si | Silicon | Latin silex, ‘flint’ (originally silicium) |

| 15 | P | Phosphorus | Greek phōsphóros, ‘light-bearing’ |

| 16 | S | Sulfur | Latin sulphur, ‘brimstone’ |

| 17 | Cl | Chlorine | Greek chlōrós, ‘greenish yellow’ |

| 18 | Ar | Argon | Greek argós, ‘idle’ (because of its inertness) |

| 19 | K | Potassium | Neo-Latin potassa, ‘potash’ (the symbol K is derived from Latin kalium) |

| 20 | Ca | Calcium | Latin calx, ‘lime’ |

| 21 | Sc | Scandium | Latin Scandia, ‘Scandinavia’ |

| 22 | Ti | Titanium | Titans, the sons of the Earth goddess of Greek mythology |

| 23 | V | Vanadium | Vanadis, an Old Norse name for the Scandinavian goddess Freyja |

| 24 | Cr | Chromium | Greek chróma, ‘colour’ |

| 25 | Mn | Manganese | corrupted from magnesia negra; see Magnesium |

| 26 | Fe | Iron | English word (the symbol Fe is derived from Latin ferrum) |

| 27 | Co | Cobalt | German Kobold, ‘goblin’ |

| 28 | Ni | Nickel | Nickel, a mischievous sprite of German miner mythology |

| 29 | Cu | Copper | English word, from Latin cuprum, from Ancient Greek Kýpros ‘Cyprus’ |

| 30 | Zn | Zinc | Most likely from German Zinke, ‘prong’ or ‘tooth’, though some suggest Persian sang, ‘stone’ |

| 31 | Ga | Gallium | Latin Gallia, ‘France’ |

| 32 | Ge | Germanium | Latin Germania, ‘Germany’ |

| 33 | As | Arsenic | French arsenic, from Greek arsenikón ‘yellow arsenic’ (influenced by arsenikós, ‘masculine’ or ‘virile’), from a West Asian wanderword ultimately from Old Iranian *zarniya-ka, ‘golden’ |

| 34 | Se | Selenium | Greek selḗnē, ‘moon’ |

| 35 | Br | Bromine | Greek brômos, ‘stench’ |

| 36 | Kr | Krypton | Greek kryptós, ‘hidden’ |

| 37 | Rb | Rubidium | Latin rubidus, ‘deep red’ |

| 38 | Sr | Strontium | Strontian, a village in Scotland |

| 39 | Y | Yttrium | Ytterby, a village in Sweden |

| 40 | Zr | Zirconium | zircon, a mineral |

| 41 | Nb | Niobium | Niobe, daughter of king Tantalus from Greek mythology |

| 42 | Mo | Molybdenum | Greek molýbdaina, ‘piece of lead’, from mólybdos, ‘lead’ |

| 43 | Tc | Technetium | Greek tekhnētós, ‘artificial’ |

| 44 | Ru | Ruthenium | Neo-Latin Ruthenia, ‘Russia’ |

| 45 | Rh | Rhodium | Greek rhodóeis, ‘rose-coloured’, from rhódon, ‘rose’ |

| 46 | Pd | Palladium | the asteroid Pallas, considered a planet at the time |

| 47 | Ag | Silver | English word (The symbol derives from Latin argentum) |

| 48 | Cd | Cadmium | Neo-Latin cadmia, from King Kadmos |

| 49 | In | Indium | Latin indicum, ‘indigo’ (colour found in its spectrum) |

| 50 | Sn | Tin | English word (The symbol derives from Latin stannum) |

| 51 | Sb | Antimony | Latin antimonium, the origin of which is uncertain: folk etymologies suggest it is derived from Greek antí (‘against’) + mónos (‘alone’), or Old French anti-moine, ‘Monk’s bane’, but it could plausibly be from or related to Arabic ʾiṯmid, ‘antimony’, reformatted as a Latin word. (The symbol derives from Latin stibium ‘stibnite’.) |

| 52 | Te | Tellurium | Latin tellus, ‘the ground, earth’ |

| 53 | I | Iodine | French iode, from Greek ioeidḗs, ‘violet’ |

| 54 | Xe | Xenon | Greek xénon, neuter form of xénos ‘strange’ |

| 55 | Cs | Caesium | Latin caesius, ‘sky-blue’ |

| 56 | Ba | Barium | Greek barýs, ‘heavy’ |

| 57 | La | Lanthanum | Greek lanthánein, ‘to lie hidden’ |

| 58 | Ce | Cerium | the dwarf planet Ceres, considered a planet at the time |

| 59 | Pr | Praseodymium | Greek prásios dídymos, ‘green twin’ |

| 60 | Nd | Neodymium | Greek néos dídymos, ‘new twin’ |

| 61 | Pm | Promethium | Prometheus of Greek mythology |

| 62 | Sm | Samarium | samarskite, a mineral named after Colonel Vasili Samarsky-Bykhovets, Russian mine official |

| 63 | Eu | Europium | Europe |

| 64 | Gd | Gadolinium | gadolinite, a mineral named after Johan Gadolin, Finnish chemist, physicist and mineralogist |

| 65 | Tb | Terbium | Ytterby, a village in Sweden |

| 66 | Dy | Dysprosium | Greek dysprósitos, ‘hard to get’ |

| 67 | Ho | Holmium | Neo-Latin Holmia, ‘Stockholm’ |

| 68 | Er | Erbium | Ytterby, a village in Sweden |

| 69 | Tm | Thulium | Thule, the ancient name for an unclear northern location |

| 70 | Yb | Ytterbium | Ytterby, a village in Sweden |

| 71 | Lu | Lutetium | Latin Lutetia, ‘Paris’ |

| 72 | Hf | Hafnium | Neo-Latin Hafnia, ‘Copenhagen’ (from Danish havn) |

| 73 | Ta | Tantalum | King Tantalus, father of Niobe from Greek mythology |

| 74 | W | Tungsten | Swedish tung sten, ‘heavy stone’ (The symbol is from wolfram, the old name of the tungsten mineral wolframite) |

| 75 | Re | Rhenium | Latin Rhenus, ‘the Rhine’ |

| 76 | Os | Osmium | Greek osmḗ, ‘smell’ |

| 77 | Ir | Iridium | Iris, the Greek goddess of the rainbow |

| 78 | Pt | Platinum | Spanish platina, ‘little silver’, from plata ‘silver’ |

| 79 | Au | Gold | English word (The symbol derives from Latin aurum) |

| 80 | Hg | Mercury | Mercury, Roman god of commerce, communication, and luck, known for his speed and mobility (The symbol is from the element’s Latin name hydrargyrum, derived from Greek hydrárgyros, ‘water-silver’) |

| 81 | Tl | Thallium | Greek thallós, ‘green shoot or twig’ |

| 82 | Pb | Lead | English word (The symbol derives from Latin plumbum) |

| 83 | Bi | Bismuth | German Wismut, from weiß Masse ‘white mass’, unless from Arabic |

| 84 | Po | Polonium | Latin Polonia, ‘Poland’ (the home country of Marie Curie) |

| 85 | At | Astatine | Greek ástatos, ‘unstable’ |

| 86 | Rn | Radon | radium |

| 87 | Fr | Francium | France |

| 88 | Ra | Radium | French radium, from Latin radius, ‘ray’ |

| 89 | Ac | Actinium | Greek aktís, ‘ray’ |

| 90 | Th | Thorium | Thor, the Scandinavian god of thunder |

| 91 | Pa | Protactinium | proto- (from Greek prôtos, ‘first, before’) + actinium, which is produced through the radioactive decay of protactinium |

| 92 | U | Uranium | Uranus, the seventh planet in the Solar System |

| 93 | Np | Neptunium | Neptune, the eighth planet in the Solar System |

| 94 | Pu | Plutonium | the dwarf planet Pluto, considered the ninth planet in the Solar System at the time |

| 95 | Am | Americium | The Americas, as the element was first synthesised on the continent, by analogy with europium |

| 96 | Cm | Curium | Pierre Curie and Marie Curie, French physicists and chemists |

| 97 | Bk | Berkelium | Berkeley, California, where the element was first synthesised, by analogy with terbium |

| 98 | Cf | Californium | California, where the element was first synthesised |

| 99 | Es | Einsteinium | Albert Einstein, German physicist |

| 100 | Fm | Fermium | Enrico Fermi, Italian physicist |

| 101 | Md | Mendelevium | Dmitri Mendeleev, Russian chemist and inventor who proposed the periodic table |

| 102 | No | Nobelium | Alfred Nobel, Swedish chemist and engineer |

| 103 | Lr | Lawrencium | Ernest O. Lawrence, American physicist |

| 104 | Rf | Rutherfordium | Ernest Rutherford, British chemist and physicist |

| 105 | Db | Dubnium | Dubna, Russia, where the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research is located |

| 106 | Sg | Seaborgium | Glenn T. Seaborg, American chemist |

| 107 | Bh | Bohrium | Niels Bohr, Danish physicist |

| 108 | Hs | Hassium | Neo-Latin Hassia, ‘Hesse’ (a state in Germany) |

| 109 | Mt | Meitnerium | Lise Meitner, Austrian physicist |

| 110 | Ds | Darmstadtium | Darmstadt, Germany, where the element was first synthesised |

| 111 | Rg | Roentgenium | Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, German physicist |

| 112 | Cn | Copernicium | Nicolaus Copernicus, Polish astronomer |

| 113 | Nh | Nihonium | Japanese Nihon, ‘Japan’ (where the element was first synthesised) |

| 114 | Fl | Flerovium | Flerov Laboratory of Nuclear Reactions, part of JINR, where the element was synthesised; itself named after Georgy Flyorov, Russian physicist |

| 115 | Mc | Moscovium | Moscow Oblast, Russia, where the element was first synthesised |

| 116 | Lv | Livermorium | Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in Livermore, California, which collaborated with JINR on its synthesis |

| 117 | Ts | Tennessine | Tennessee, United States |

| 118 | Og | Oganesson | Yuri Oganessian, Russian physicist |

Symbols and names not currently used[edit]

The following is a list of symbols and names formerly used or suggested for elements, including symbols for placeholder names and names given by discredited claimants for discovery.

| Symbol | Name | Atomic number |

Notes | Why not used |

Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Argon | 18 | A used for Argon until 1957. Current symbol is Ar. | [nb 1] | [4] |

| Ab | Alabamine | 85 | Discredited claim to discovery of astatine. | [nb 2] | [5][6] |

| Ad | Aldebaranium | 70 | Former name for ytterbium. | [nb 2] | |

| Ah | Anglohelvetium | 85 | Discredited claim to discovery of astatine. | [nb 2] | [7] |

| Ak | Alkalinium | 87 | Discredited claim to discovery of francium. | [nb 2] | [5] |

| Am | Alabamine | 85 | Discredited claim to discovery of astatine. The symbol Am is now used for americium. | [nb 2] | [5][6] |

| An | Athenium | 99 | Proposed name for einsteinium. | [nb 3] | |

| Ao | Ausonium | 93 | Discredited claim to discovery of neptunium. | [nb 2] | [5] |

| At | Austriacum | 84 | Discredited claim to discovery of polonium. The symbol At is now used for astatine. | [nb 2] | |

| Az | Azote | 7 | Former name for nitrogen. | [nb 1] | |

| Bo | Bohemium | 93 | Discredited claim to discovery of neptunium. | [nb 2] | |

| Bo | Boron | 5 | Current symbol is B. | [nb 1] | |

| Bv | Brevium | 91 | Former name for protactinium. | [nb 1] | |

| Bz | Berzelium | 90 | Baskerville wrongly believed berzelium to be a new element. Was actually thorium. | [7] | |

| Cb | Columbium | 41 | Former name for niobium. | [nb 1] | [5][7] |

| Ch | Chromium | 24 | Current symbol is Cr. | [nb 1] | |

| Cl | Columbium | 41 | Former name for niobium. The symbol Cl is now used for chlorine. | [nb 1] | |

| Cm | Catium | 87 | Proposed name for francium. The symbol Cm is now used for curium. | [nb 3] | |

| Cn | Carolinium | 90 | Baskerville wrongly believed carolinium to be a new element. Was actually thorium. The symbol Cn is now used for copernicium. | [7] | |

| Cp | Cassiopeium | 71 | Former name for lutetium. | [nb 1] | |

| Cp | Copernicium | 112 | Current symbol is Cn. | [nb 1] | |

| Ct | Celtium | 72 | Discredited claim to discovery of hafnium. | [nb 2] | |

| Ct | Centurium | 100 | Proposed name for fermium. | [nb 3] | |

| Cy | Cyclonium | 61 | Proposed name for promethium. | [nb 3] | |

| D | Didymium | 59/60 | Mixture of the elements praseodymium and neodymium. Mosander wrongly believed didymium to be an element. | [8] | |

| Da | Davyum | 43 | Discredited claim to discovery of technetium. | [nb 2] | [5] |

| Db | Dubhium | 69 | Eder wrongly believed dubhium to be a new element. Was actually thulium. The symbol Db is now used for dubnium. | ||

| Db | Dubnium | 104 | Proposed name for rutherfordium. The symbol and name were instead used for element 105. | [nb 1][nb 3] | [5] |

| Dc | Decipium | 62 | Delafontaine wrongly believed decipium to be a new element. Was actually samarium. | ||

| Dc | Dvicaesium | 87 | Name given by Mendeleev to an as of then undiscovered element. When discovered, francium closely matched the prediction. | [nb 3][nb 4] | |

| De | Denebium | 69 | Eder wrongly believed denebium to be a new element. Was actually thulium. | ||

| Di | Didymium | 59/60 | Mixture of the elements praseodymium and neodymium. Mosander wrongly believed didymium to be an element. | [8] | |

| Do | Dor | 85 | Discredited claim to discovery of astatine. | [nb 2] | [7] |

| Dn | Dubnadium | 118 | Proposed name for oganesson. | [nb 3] | |

| Dp | Decipium | 62 | Delafontaine wrongly believed decipium to be a new element. Was actually samarium. | ||

| Ds | Dysprosium | 66 | Current symbol is Dy. The symbol Ds is now used for darmstadtium. | [nb 1] | |

| Dt | Dvitellurium | 84 | Name given by Mendeleev to an as of then undiscovered element. When discovered, polonium closely matched the prediction. | [nb 3][nb 4] | |

| E | Einsteinium | 99 | Current symbol is Es. | [nb 1] | |

| E | Erbium | 68 | Current symbol is Er. | [nb 1] | |

| Ea | Ekaaluminium | 31 | Name given by Mendeleev to an as of then undiscovered element. When discovered, gallium closely matched the prediction. | [nb 3][nb 4] | |

| Eb | Ekaboron | 21 | Name given by Mendeleev to an as of then undiscovered element. When discovered, scandium closely matched the prediction. | [nb 3][nb 4] | [5] |

| Eb | Erebodium | 42 | Alexander Pringle wrongly believed erebodium to be a new element. Was actually molybdenum. | ||

| El | Ekaaluminium | 31 | Name given by Mendeleev to an as of then undiscovered element. When discovered, gallium closely matched the prediction. | [nb 3][nb 4] | [5] |

| Em | Ekamanganese | 43 | Name given by Mendeleev to an as of then undiscovered element. When discovered, technetium closely matched the prediction. | [nb 3][nb 4] | [5] |

| Em | Emanation | 86 | Also called «radium emanation», the name was originally given by Friedrich Ernst Dorn in 1900. In 1923, this element officially became radon (the name given at one time to 222Rn, an isotope identified in the decay chain of radium). |

[nb 1] | [5] |

| Em | Emanium | 89 | Alternate name formerly proposed for actinium. | [nb 3] | |

| Es | Ekasilicon | 32 | Name given by Mendeleev to a then undiscovered element. When discovered, germanium closely matched the prediction. The symbol Es is now used for einsteinium. |

[nb 3][nb 4] | [5] |

| Es | Esperium | 94 | Discredited claim to discovery of plutonium. The symbol Es is now used for einsteinium. | [nb 2] | [5] |

| Et | Ekatantalum | 91 | Name given by Mendeleev to an as of then undiscovered element. When discovered, protactinium closely matched the prediction. | [nb 3][nb 4] | |

| Ex | Euxenium | 72 | Discredited claim to discovery of hafnium. | [nb 2] | |

| Fa | Francium | 87 | Current symbol is Fr. | [nb 1] | |

| Fl | Florentium | 61 | Discredited claim to discovery of promethium. The symbol Fl is now used for flerovium. | [nb 2] | |

| Fl | Fluorine | 9 | Current symbol is F. The symbol Fl is now used for flerovium. | [nb 1] | |

| Fr | Florentium | 61 | Discredited claim to discovery of promethium. The symbol Fr is now used for francium. | [nb 2] | [5] |

| G | Glucinium | 4 | Former name for beryllium. | [nb 1] | |

| Gh | Ghiorsium | 118 | Discredited claim to discovery of oganesson. | [nb 2] | |

| Gl | Glucinium | 4 | Former name for beryllium. | [nb 1] | [5] |

| Ha | Hahnium | 105 | Proposed name for dubnium. | [nb 3] | |

| Hn | Hahnium | 108 | Proposed name for hassium. | [nb 3] | [5] |

| Hv | Helvetium | 85 | Discredited claim to discovery of astatine. | [nb 2] | [7] |

| Hy | Mercury | 80 | Hy from the Greek hydrargyrum for «liquid silver». Current symbol is Hg. | [nb 1] | [4] |

| I | Iridium | 77 | Current symbol is Ir. The symbol I is now used for iodine. | [nb 1] | |

| Ic | Incognitium | 65 | Demarçay wrongly believed incognitium to be a new element. Was actually terbium. | ||

| Il | Illinium | 61 | Discredited claim to discovery of promethium. | [nb 2] | [5] |

| Il | Ilmenium | 41/73 | Mixture of the elements niobium and tantalum. R. Hermann wrongly believed ilmenium to be an element. | ||

| Io | Ionium | 65 | Demarçay wrongly believed ionium to be a new element. Was actually terbium. | ||

| J | Jodium | 53 | Former name for iodine. | [nb 1] | |

| Jg | Jargonium | 72 | Discredited claim to discovery of hafnium. | [nb 2] | [5] |

| Jl | Joliotium | 105 | Proposed name for dubnium. | [nb 3] | [5] |

| Jp | Japonium | 113 | Proposed name for nihonium. | [nb 3] | |

| Ka | Potassium | 19 | Current symbol is K. | [nb 1] | |

| Ku | Kurchatovium | 104 | Proposed name for rutherfordium. | [nb 3] | [5] |

| L | Lithium | 3 | Current symbol is Li. | [nb 1] | |

| Lw | Lawrencium | 103 | Current symbol is Lr. | [nb 1] | |

| M | Muriaticum | 17 | Former name for chlorine. | [nb 1] | |

| Ma | Manganese | 25 | Current symbol is Mn. | [nb 1] | |

| Ma | Masurium | 43 | Disputed claim to discovery of technetium. | [nb 2] | [5] |

| Md | Mendelevium | 97 | Proposed name for berkelium. The symbol and name were later used for element 101. | [nb 1][nb 3] | |

| Ml | Moldavium | 87 | Discredited claim to discovery of francium. | [nb 2] | [7] |

| Ms | Magnesium | 12 | Current symbol is Mg. | [nb 1] | |

| Ms | Masrium | 88 | Discredited claim to discovery of radium. | [nb 2] | |

| Ms | Masurium | 43 | Disputed claim to discovery of technetium. | [nb 2] | |

| Ms | Mosandrium | 65 | Smith wrongly believed mosandrium to be a new element. Was actually terbium. | ||

| Mv | Mendelevium | 101 | Current symbol is Md. | [nb 1] | |

| Ng | Norwegium | 72 | Discredited claim to discovery of hafnium. | [nb 2] | |

| No | Norium | 72 | Discredited claim to discovery of hafnium. The symbol No is now used for nobelium. | [nb 2] | |

| Np | Neptunium | 91 | Discredited claim to discovery of protactinium. The symbol and name were later used for element 93. | [nb 2] | [9] |

| Np | Nipponium | 43 | Discredited claim to discovery of technetium. The symbol Np is now used for neptunium. | [nb 2] | [5] |

| Ns | Nielsbohrium | 105 | Proposed name for dubnium. | [nb 3] | [5] |

| Ns | Nielsbohrium | 107 | Proposed name for bohrium. | [nb 3] | [5] |

| Nt | Niton | 86 | Former name for radon. | [nb 1] | [5] |

| Ny | Neoytterbium | 70 | Former name for ytterbium. | [nb 1] | |

| P | Lead | 82 | Current symbol is Pb. The symbol P is now used for phosphorus. | [nb 1] | |

| Pa | Palladium | 46 | Current symbol is Pd. The symbol Pa is now used for protactinium. | [nb 1] | |

| Pe | Pelopium | 41 | Former name for niobium. | [nb 1] | |

| Ph | Phosphorus | 15 | Current symbol is P. | [nb 1] | |

| Pl | Palladium | 46 | Current symbol is Pd. | [nb 1] | |

| Pm | Polymnestum | 33 | Alexander Pringle wrongly believed polymnestum to be a new element. Was actually arsenic. The symbol Pm is now used for promethium. | ||

| Po | Potassium | 19 | Current symbol is K. The symbol Po is now used for polonium. | [nb 1] | |

| Pp | Philippium | 67 | Delafontaine wrongly believed philippium to be a new element. Was actually holmium. | ||

| R | Rhodium | 45 | Current symbol is Rh. (The symbol is now sometimes used for an alkyl group.) | [nb 1] | |

| Rd | Radium | 88 | Current symbol is Ra. | [nb 1] | |

| Rf | Rutherfordium | 106 | Proposed name for seaborgium. The symbol and name were instead used for element 104. | [nb 1][nb 3] | [5] |

| Ro | Rhodium | 45 | Current symbol is Rh. | [nb 1] | |

| Sa | Samarium | 62 | Current symbol is Sm. | [nb 1] | [5] |

| So | Sodium | 11 | Current symbol is Na. | [nb 1] | |

| Sq | Sequanium | 93 | Discredited claim to discovery of neptunium. | [nb 2] | |

| St | Antimony | 51 | Current symbol is Sb. | [nb 1] | |

| St | Tin | 50 | Current symbol is Sn. | [nb 1] | |

| Tm | Trimanganese | 75 | Name given by Mendeleev to an as of then undiscovered element. When discovered, rhenium closely matched the prediction. The symbol Tm is now used for thulium. | [nb 3][nb 4] | |

| Tn | Tungsten | 74 | Current symbol is W. | [nb 1] | |

| Tr | Terbium | 65 | Current symbol is Tb. | [nb 1] | |

| Tu | Thulium | 69 | Current symbol is Tm. | [nb 1] | |

| Tu | Tungsten | 74 | Current symbol is W. | [nb 1] | |

| Unb | Unnilbium | 102 | Temporary name given to nobelium until it was permanently named by IUPAC. | [nb 4] | |

| Une | Unnilennium | 109 | Temporary name given to meitnerium until it was permanently named by IUPAC. | [nb 4] | |

| Unh | Unnilhexium | 106 | Temporary name given to seaborgium until it was permanently named by IUPAC. | [nb 4] | |

| Uno | Unniloctium | 108 | Temporary name given to hassium until it was permanently named by IUPAC. | [nb 4] | |

| Unp | Unnilpentium | 105 | Temporary name given to dubnium until it was permanently named by IUPAC. | [nb 4] | |

| Unq | Unnilquadium | 104 | Temporary name given to rutherfordium until it was permanently named by IUPAC. | [nb 4] | |

| Uns | Unnilseptium | 107 | Temporary name given to bohrium until it was permanently named by IUPAC. | [nb 4] | |

| Unt | Unniltrium | 103 | Temporary name given to lawrencium until it was permanently named by IUPAC. | [nb 4] | |

| Unu | Unnilunium | 101 | Temporary name given to mendelevium until it was permanently named by IUPAC. | [nb 4] | |

| Uub | Ununbium | 112 | Temporary name given to copernicium until it was permanently named by IUPAC. | [nb 4] | |

| Uuh | Ununhexium | 116 | Temporary name given to livermorium until it was permanently named by IUPAC. | [nb 4] | |

| Uun | Ununnilium | 110 | Temporary name given to darmstadtium until it was permanently named by IUPAC. | [nb 4] | |

| Uuo | Ununoctium | 118 | Temporary name given to oganesson until it was permanently named by IUPAC. | [nb 4] | |

| Uup | Ununpentium | 115 | Temporary name given to moscovium until it was permanently named by IUPAC. | [nb 4] | |

| Uuq | Ununquadium | 114 | Temporary name given to flerovium until it was permanently named by IUPAC. | [nb 4] | |

| Uus | Ununseptium | 117 | Temporary name given to tennessine until it was permanently named by IUPAC. | [nb 4] | |

| Uut | Ununtrium | 113 | Temporary name given to nihonium until it was permanently named by IUPAC. | [nb 4] | |

| Uuu | Unununium | 111 | Temporary name given to roentgenium until it was permanently named by IUPAC. | [nb 4] | |

| Ur | Uralium | 75 | Discredited claim to discovery of rhenium. | [nb 2] | |

| Ur | Uranium | 92 | Current symbol is U. | [nb 1] | |

| Vc | Victorium | 64 | Crookes wrongly believed victorium to be a new element. Was actually gadolinium. | ||

| Vi | Victorium | 64 | Crookes wrongly believed victorium to be a new element. Was actually gadolinium. | ||

| Vi | Virginium | 87 | Discredited claim to discovery of francium. | [nb 2] | [5] |

| Vm | Virginium | 87 | Discredited claim to discovery of francium. | [nb 2] | [5] |

| Va | Vanadium | 23 | Current symbol is V. | [nb 1] | |

| Wo | Tungsten | 74 | Current symbol is W. | [nb 1] | |

| X | Xenon | 54 | Current symbol is Xe. The symbol X is now used for any halogen. | [nb 1] | |

| Yt | Yttrium | 39 | Current symbol is Y. | [nb 1] | [5] |

Alchemical symbols[edit]

The following ideographic symbols were employed in alchemy to symbolize elements known since ancient times. Not included in this list are spurious elements, such as the classical elements fire and water or phlogiston, and substances now known to be compounds. Many more symbols were in at least sporadic use: one early 17th-century alchemical manuscript lists 22 symbols for mercury alone.[10]

Planetary names and symbols for the metals – the seven planets and seven metals known since Classical times in Europe and the Mideast – was ubiquitous in alchemy. The association of what are anachronistically known as planetary metals started breaking down with the discovery of antimony, bismuth and zinc in the 16th century. Alchemists would typically call the metals by their planetary names, e.g. «Saturn» for lead and «Mars» for iron; compounds of tin, iron and silver continued to be called «jovial», «martial» and «lunar»; or «of Jupiter», «of Mars» and «of the moon», through the 17th century. The tradition remains today with the name of the element mercury, where chemists decided the planetary name was preferable to common names like «quicksilver», and in a few archaic terms such as lunar caustic (silver nitrate) and saturnism (lead poisoning).[10]

| Symbol | Element | Atomic number |

Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphorus | 15 | (discovered late) | ||

| 🜍 | Sulfur | 16 | used by Newton | |

| Manganese | 25 | late; used by Torbern Bergman (1775) | ||

| ♂ | Iron | 26 | classical planetary metal of Mars | |

| 🜶 | Cobalt | 27 | late; used by Bergman | |

| Nickel | 28 | late; used by Bergman (old positional variant of arsenic, previously used for regulus of sulfur) | ||

| Zinc | 30 | late; used by Bergman | ||

| ♀ | Copper | 29 | classical planetary metal of Venus | |

| 🜺 | Arsenic | 33 | ||

| ☾ | Silver | 47 | classical planetary metal of the Moon | |

| 🜛 | ||||

| ♃ | Tin | 50 | classical planetary metal of Jupiter | |

| ♁ | Antimony | 51 | the newly discovered «eighth metal» was given the symbol for the Earth, which was recognized as a planet by that time | |

| Platinum | 78 | late; used by Bergman et al.: a compound of ☉ gold and ☾ silver | ||

| ⛢ | late; symbol invented for the newly discovered planet Uranus | |||

| 🜚 | Gold | 79 | classical variant | |

| ☉ | medieval variant; planetary metal for the Sun | |||

| ☿ | Mercury | 80 | classical planetary metal for Mercury | |

| ♄ | Lead | 82 | classical planetary metal for Saturn | |

| ♆ | Bismuth | 83 | used by Newton | |

| ♉︎ | used by Bergman |

Daltonian symbols[edit]

Dalton’s symbols for the more common elements, as of 1806, and the relative weights he calculated. The symbols for magnesium and calcium («lime») were replaced by 1808, and that for gold was simplified.

The following symbols were employed by John Dalton in the early 1800s as the periodic table of elements was being formulated. Not included in this list are substances now known to be compounds, such as certain rare-earth mineral blends. Modern alphabetic notation was introduced in 1814 by Jöns Jakob Berzelius; its precursor can be seen in Dalton’s circled letters for the metals, especially in his augmented table from 1810.[11]

A trace of Dalton’s conventions also survives in ball-and-stick models of molecules, where balls for carbon are black and for oxygen red.

| Symbol | Dalton’s name | Modern name | Atomic number |

Notes | Refs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| img. | char. | |||||

| ☉ | hydrogen | 1 | or ⊙ | [12] | ||

| glucine | beryllium | 4 | alchemical symbol for ‘sugar’ | [13] | ||

| ● | carbone, carbon | carbon | 6 | [12] | ||

| ⦶ | azote | nitrogen/azote | 7 | alchemical symbol for niter | [12] | |

| ○ | oxygen | 8 | or ◯ | [12] | ||

| ⦷ | soda | sodium | 11 | [12] | ||

| ⊛ | magnesia | magnesium | 12 | alchemical symbol for magnesia | [12] | |

| alumine | aluminium | 13 | (4 dots) | [12] | ||

| 🟕 | silex | silicon | 14 | [13] | ||

| phosphorus | 15 | (3 radii) | [12] | |||

| 🜨 | sulphur | 16 | [12] | |||

| potash | potassium | 19 | (3 vertical lines) | [12] | ||

| ⦾ | lime | calcium | 20 | or ◎ | [12] | |

| titanium | 22 | (enclosing circle) Tit⃝ | [13] | |||

| manganese | 25 | (enclosing circle) Ma⃝ | [13] | |||

| Ⓘ | iron | 26 | [12] | |||

| Ⓝ | nickel | 28 | [12] | |||

| cobalt | 27 | (enclosing circle) Cob⃝ | [13] | |||

| Ⓒ | copper | 29 | (black letter in red circle) | [12] | ||

| Ⓩ | zinc | 30 | [12] | |||

| arsenic | 33 | (enclosing circle) Ar⃝ | [13] | |||

| strontian | strontium | 38 | (4 ticks) | [12] | ||

| ⊕︀︀ | yttria | yttrium | 39 | (plus does not touch circle) | [13] | |

| zircone | zirconium | 40 | (vertical zigzag) | [13] | ||

| Ⓢ | silver | 47 | [12] | |||

| Ⓣ | tin | 50 | [13] | |||

| antimony | 51 | (enclosing circle) An⃝ | [13] | |||

| barytes | barium | 56 | (6 ticks) | [12] | ||

| cerium | 58 | (enclosing circle) Ce⃝ | [13] | |||

| tungsten | 74 | (enclosing circle) Tu⃝ | [13] | |||

| Ⓟ | platina | platinum | 78 | (black letter in red circle) | [12] | |

| Ⓖ | gold | 79 | [12] | |||

| mercury | 80 | (dotted inside perimeter) | [12] | |||

| Ⓛ | lead | 82 | [12] | |||

| Ⓑ | bismuth | 83 | [13] | |||

| Ⓤ | uranium | 92 | [13] |

Symbols for named isotopes[edit]

The following is a list of isotopes of elements given in the previous tables which have been designated unique symbols. By this it is meant that a comprehensive list of current systematic symbols (in the uAtom form) is not included in the list and can instead be found in the Isotope index chart. The symbols for the named isotopes of hydrogen, deuterium (D), and tritium (T) are still in use today, as is thoron (Tn) for radon-220 (though not actinon; An is usually used instead for a generic actinide). Heavy water and other deuterated solvents are commonly used in chemistry, and it is convenient to use a single character rather than a symbol with a subscript in these cases. The practice also continues with tritium compounds. When the name of the solvent is given, a lowercase d is sometimes used. For example, d6-benzene and C6D6 can be used instead of C6[2H6].[14]

The symbols for isotopes of elements other than hydrogen and radon are no longer in use within the scientific community. Many of these symbols were designated during the early years of radiochemistry, and several isotopes (namely those in the decay chains of actinium, radium, and thorium) bear placeholder names using the early naming system devised by Ernest Rutherford.[15]

| Symbol | Name | Atomic number |

Origin of symbol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ac | Actinium | 89 | From the Greek aktinos. Name restricted at one time to 227Ac, an isotope of actinium. This named isotope later became the official name for element 89. |

| AcA | Actinium A | 84 | From actinium and A. Placeholder name given at one time to 215Po, an isotope of polonium identified in the decay chain of actinium. |

| AcB | Actinium B | 82 | From actinium and B. Placeholder name given at one time to 211Pb, an isotope of lead identified in the decay chain of actinium. |

| AcC | Actinium C | 83 | From actinium and C. Placeholder name given at one time to 211Bi, an isotope of bismuth identified in the decay chain of actinium. |

| AcC′ | Actinium C′ | 84 | From actinium and C′. Placeholder name given at one time to 211Po, an isotope of polonium identified in the decay chain of actinium. |

| AcC″ | Actinium C″ | 81 | From actinium and C″. Placeholder name given at one time to 207Tl, an isotope of thallium identified in the decay chain of actinium. |

| AcK | Actinium K | 87 | Name given at one time to 223Fr, an isotope of francium identified in the decay chain of actinium. |

| AcU | Actino-uranium | 92 | Name given at one time to 235U, an isotope of uranium. |

| AcX | Actinium X | 88 | Name given at one time to 223Ra, an isotope of radium identified in the decay chain of actinium. |

| An | Actinon | 86 | From actinium and emanation. Name given at one time to 219Rn, an isotope of radon identified in the decay chain of actinium. |

| D | Deuterium | 1 | From the Greek deuteros. Name given to 2H. |

| Io | Ionium | 90 | Name given to 230Th, an isotope of thorium identified in the decay chain of uranium. |

| MsTh1 | Mesothorium 1 | 88 | Name given at one time to 228Ra, an isotope of radium. |

| MsTh2 | Mesothorium 2 | 89 | Name given at one time to 228Ac, an isotope of actinium. |

| Pa | Protactinium | 91 | From the Greek protos and actinium. Name restricted at one time to 231Pa, an isotope of protactinium. This named isotope later became the official name for element 91. |

| Ra | Radium | 88 | From the Latin radius. Name restricted at one time to 226Ra, an isotope of radium. This named isotope later became the official name for element 88. |

| RaA | Radium A | 84 | From radium and A. Placeholder name given at one time to 218Po, an isotope of polonium identified in the decay chain of radium. |

| RaB | Radium B | 82 | From radium and B. Placeholder name given at one time to 214Pb, an isotope of lead identified in the decay chain of radium. |

| RaC | Radium C | 83 | From radium and C. Placeholder name given at one time to 214Bi, an isotope of bismuth identified in the decay chain of radium. |

| RaC′ | Radium C′ | 84 | From radium and C′. Placeholder name given at one time to 214Po, an isotope of polonium identified in the decay chain of radium. |

| RaC″ | Radium C″ | 81 | From radium and C″. Placeholder name given at one time to 210Tl, an isotope of thallium identified in the decay chain of radium. |

| RaD | Radium D | 82 | From radium and D. Placeholder name given at one time to 210Pb, an isotope of lead identified in the decay chain of radium. |

| RaE | Radium E | 83 | From radium and E. Placeholder name given at one time to 210Bi, an isotope of bismuth identified in the decay chain of radium. |

| RaE″ | Radium E″ | 81 | From radium and E″. Placeholder name given at one time to 206Tl, an isotope of thallium identified in the decay chain of radium. |

| RaF | Radium F | 84 | From radium and F. Placeholder name given at one time to 210Po, an isotope of polonium identified in the decay chain of radium. |

| RdAc | Radioactinium | 90 | Name given at one time to 227Th, an isotope of thorium. |

| RdTh | Radiothorium | 90 | Name given at one time to 228Th, an isotope of thorium. |

| Rn | Radon | 86 | From radium and emanation. Name restricted at one time to 222Rn, an isotope of radon identified in the decay chain of radium. This named isotope later became the official name for element 86 in 1923. |

| T | Tritium | 1 | From the Greek tritos. Name given to 3H. |

| Th | Thorium | 90 | After Thor. Name restricted at one time to 232Th, an isotope of thorium. This named isotope later became the official name for element 90. |

| ThA | Thorium A | 84 | From thorium and A. Placeholder name given at one time to 216Po, an isotope of polonium identified in the decay chain of thorium. |

| ThB | Thorium B | 82 | From thorium and B. Placeholder name given at one time to 212Pb, an isotope of lead identified in the decay chain of thorium. |

| ThC | Thorium C | 83 | From thorium and C. Placeholder name given at one time to 212Bi, an isotope of bismuth identified in the decay chain of thorium. |

| ThC′ | Thorium C′ | 84 | From thorium and C′. Placeholder name given at one time to 212Po, an isotope of polonium identified in the decay chain of thorium. |

| ThC″ | Thorium C″ | 81 | From thorium and C″. Placeholder name given at one time to 208Tl, an isotope of thallium identified in the decay chain of thorium. |

| ThX | Thorium X | 88 | Name given at one time to 224Ra, an isotope of radium identified in the decay chain of thorium. |

| Tn | Thoron | 86 | From thorium and emanation. Name given at one time to 220Rn, an isotope of radon identified in the decay chain of thorium. |

| UI | Uranium I | 92 | Name given at one time to 238U, an isotope of uranium. |

| UII | Uranium II | 92 | Name given at one time to 234U, an isotope of uranium. |

| UX1 | Uranium X1 | 90 | Name given at one time to 234Th, an isotope of thorium identified in the decay chain of uranium. |

| UX2 | Uranium X2 | 91 | Name given at one time to 234mPa, an isotope of protactinium identified in the decay chain of uranium. |

| UY | Uranium Y | 90 | Name given at one time to 231Th, an isotope of thorium identified in the decay chain of uranium. |

| UZ | Uranium Z | 91 | Name given at one time to 234Pa, an isotope of protactinium identified in the decay chain of uranium. |

Other symbols[edit]

- In Chinese, each chemical element has a dedicated character, usually created for the purpose (see Chemical elements in East Asian languages). However, in Chinese Latin symbols are also used, especially in formulas.

General:

- A: A deprotonated acid or an anion

- An: any actinide

- B: A base, often in the context of Lewis acid–base theory or Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory

- E: any element or electrophile

- L: any ligand

- Ln: any lanthanide

- M: any metal

- Mm: mischmetall (occasionally used)[16]

- Ng: any noble gas (Rg is sometimes used, but that is also used for the element roentgenium: see above)

- Nu: any nucleophile

- R: any unspecified radical (moiety) not important to the discussion

- St: steel (occasionally used)

- X: any halogen (or sometimes pseudohalogen)

From organic chemistry:

- Ac: acetyl – (also used for the element actinium: see above)

- Ad: 1-adamantyl

- All: allyl

- Am: amyl (pentyl) – (also used for the element americium: see above)

- Ar: aryl – (also used for the element argon: see above)

- Bn: benzyl

- Bs: brosyl or (outdated) benzenesulfonyl

- Bu: butyl (i-, s-, or t— prefixes may be used to denote iso-, sec-, or tert— isomers, respectively)

- Bz: benzoyl

- Cp: cyclopentadienyl

- Cp*: pentamethylcyclopentadienyl

- Cy: cyclohexyl

- Cyp: cyclopentyl

- Et: ethyl

- Me: methyl

- Mes: mesityl (2,4,6-trimethylphenyl)

- Ms: mesyl (methylsulfonyl)

- Np: neopentyl – (also used for the element neptunium: see above)

- Ns: nosyl

- Pent: pentyl

- Ph, Φ: phenyl

- Pr: propyl – (i— prefix may be used to denote isopropyl. Also used for the element praseodymium: see above)

- R: In organic chemistry contexts, an unspecified «R» is often understood to be an alkyl group

- Tf: triflyl (trifluoromethanesulfonyl)

- Tr, Trt: trityl (triphenylmethyl)

- Ts, Tos: tosyl (para-toluenesulfonyl) – (Ts also used for the element tennessine: see above)

- Vi: vinyl

Exotic atoms:

- Mu: muonium

- Pn: protonium

- Ps: positronium

Hazard pictographs are another type of symbols used in chemistry.

See also[edit]

- List of chemical elements naming controversies

- List of elements

- Nuclear notation

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb Name changed due to a standardization of, modernization of, or update to older formerly-used symbol.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Name designated by discredited/disputed claimant.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Name proposed prior to discovery/creation of element or prior to official renaming of a placeholder name.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Temporary placeholder name.

References[edit]

- ^ IUPAC Provisional Recommendations: IR-3: Elements and Groups of Elements (PDF) (Report). IUPAC. March 2004.

- ^ «Periodic Table – Royal Society of Chemistry». www.rsc.org.

- ^ «Online Etymology Dictionary». etymonline.com.

- ^ a b Holden, N. E. (12 March 2004). «History of the Origin of the Chemical Elements and Their Discoverers». National Nuclear Data Center.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad Leal, João P. (2013). «The Forgotten Names of Chemical Elements». Foundations of Science. 19 (2): 175–183. doi:10.1007/s10699-013-9326-y. S2CID 254511660.

- ^ a b Biggs, Lindy; Knowlton, Stephen (3 February 2022). «Fred Allison». Encyclopedia of Alabama.

- ^ a b c d e f g Fontani, Marco; Costa, Mariagrazia; Orna, Mary Virginia (2014). The Lost Elements: The Periodic Table’s Shadow Side. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199383344.

- ^ a b Praseodymium on was.chemistryexplained.com.

- ^ Rang, F. (1895). «The Period-Table». The Chemical News and Journal of Physical Science. 72: 200–201.

- ^ a b Maurice Crosland (2004) Historical Studies in the Language of Chemistry

- ^ Berzelius, Jöns Jakob. «Essay on the Cause of Chemical Proportions, and on Some Circumstances Relating to Them: Together with a Short and Easy Method of Expressing Them.» Annals of Philosophy 2, Pp.443–454 (1813); 3, Pp.51–52, 93–106, 244–255, 353–364 (1814); (Subsequently republished in «A Source Book in Chemistry, 1400-1900», eds. Leicester, Henry M. & Herbert S. Klickstein. 1952.)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Dalton, John (1808). «III: On Chemical Synthesis — Section 1: Explanation of the Plates — Plate 4: Elements». A New System of Chemical Philosophy. Part I. Manchester: Printed by S. Russell for R. Bickerstaff, Strand, London. pp. 217–220.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Dalton, John (1810). «V: Compounds of two Elements — Section 12: Earths — Explanation of Plates — Plate 5: Elements». A New System of Chemical Philosophy. Part II. Manchester: Printed by Russell & Allen for R. Bickerstaff, Strand, London. pp. 546–548.

- ^ IUPAC. «Isotopically Modified Compounds». IUPAC. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ^ Morgan, G. T., ed. (1905). «Annual Reports on the Progress of Chemistry for 1904». Journal of the Chemical Society. Gurney & Jackson. 1: 268.

In view of the extraordinarily complex nature of the later changes occurring in Radium, Rutherford has proposed a new and convenient system of nomenclature. The first product of the change of the radium emanation is named radium A, the next radium B, and so on.

- ^ Jurczyk, M.; Rajewski, W.; Majchrzycki, W.; Wójcik, G. (1999-08-30). «Mechanically alloyed MmNi5-type materials for metal hydride electrodes». Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 290 (1–2): 262–266. doi:10.1016/S0925-8388(99)00202-9.

- Elementymology & Elements Multidict, element name etymologies. Retrieved July 15, 2005.

- Atomic Weights of the Elements 2001, Pure Appl. Chem. 75(8), 1107–1122, 2003. Retrieved June 30, 2005. Atomic weights of elements with atomic numbers from 1–109 taken from this source.

- IUPAC Standard Atomic Weights Revised (2005).

- WebElements Periodic Table. Retrieved June 30, 2005. Atomic weights of elements with atomic numbers 110–116 taken from this source.

- Leighton, Robert B. Principles of Modern Physics. New York: McGraw-Hill. 1959.

- Scerri, E.R. «The Periodic Table, Its Story and Its Significance». New York, Oxford University Press. 2007.

External links[edit]

- Berzelius’ List of Elements

- History of IUPAC Atomic Weight Values (1883 to 1997)

- Committee on Nomenclature, Terminology, and Symbols, American Chemical Society

В уроке 1 «Атомы и химические элементы» из курса «Химия для чайников» рассмотрим, кто и когда высказал идею о том, что все вокруг состоит из атомов; также выясним, что из себя представляет химический элемент и каким образом обозначается.

Все, что нас окружает, мы сами, Земля, на которой мы живем, состоит из самых разнообразных веществ. А из чего состоят сами вещества? Ведь их можно дробить на более мелкие части, а те, в свою очередь, на еще более мелкие. Где предел такого деления? Что представляют собой частицы, которые дальше уже нельзя раздробить обычными способами? Над этими вопросами задумывались ученые еще в глубокой древности.

Атомное строение веществ

Первые представления об атомах как мельчайших, далее неделимых частицах веществ появились у философов Древней Греции еще за 400 лет до н. э. Они считали, что каждое вещество составлено из присущих только ему атомов, т. е. существуют атомы, например, мяса, песка, дерева, воды и т. д. Другими словами, сколько есть веществ, столько и видов атомов.

Доказательств существования атомов в то время, конечно, не было, и это учение было забыто почти на две тысячи лет. И только в самом начале XIX в. идея атомного строения веществ была возрождена английским ученым Дж. Дальтоном.

Согласно его теории все вещества состоят из очень маленьких частиц — атомов. В процессе химических превращений атомы не разрушаются и не возникают вновь, а только переходят из одних веществ в другие. Они являются как бы деталями конструктора, из которых можно собирать всевозможные изделия.

Атомы — мельчайшие, химически неделимые частицы.

Химические элементы

Общее число атомов во Вселенной невообразимо велико. Однако видов атомов сравнительно немного. Каждый такой определенный вид атомов называется химическим элементом.

Химический элемент — определенный вид атомов.

Позже, после изучения строения атома, вы узнаете более точное определение этого понятия.

Всего в настоящее время известно 118 химических элементов. Атомы одного и того же элемента имеют одинаковые размеры, практически одинаковое строение и массу. Атомы разных элементов различаются между собой, прежде всего, строением, размерами, массой и целым рядом других характеристик.

На заметку: Из 118 химических элементов в природе встречается только 92, а остальные 26 получены искусственно с помощью специальных физических методов.

Из атомов такого небольшого числа химических элементов построены все вещества, существующие в природе и полученные химиками в лабораториях. А это более 60 млн веществ. Все они представляют собой самые различные сочетания атомов тех или иных элементов. Так же, как из 33 букв алфавита составлены все слова русского языка, из атомов относительно небольшого числа элементов состоят все известные вещества.

Символы химических элементов

Каждый элемент имеет свое название и условное обозначение — химический символ (знак).

Химический символ (знак) — условное обозначение химического элемента с помощью букв его латинского названия.

Символы химических элементов состоят из одной или двух букв их латинских названий. Понятно, что вторая буква нужна, чтобы различать элементы, в названиях которых первая буква одинакова. Например, элемент углерод обозначается первой буквой С его латинского названия — Carboneum (карбонеум), а элемент медь — двумя первыми буквами Cu его латинского названия — Cuprum (купрум).

Современные символы и названия наиболее распространенных элементов, необходимые вам на начальном этапе изучения химии, приведены в таблице под спойлером.

Спойлер

| Название химического элемента | Химический знак элемента | Относительная атомная масса (округленная) |

| Азот | N | 14 |

| Алюминий | Al | 27 |

| Водород | H | 1 |

| Железо | Fe | 56 |

| Золото | Au | 197 |

| Калий | K | 39 |

| Кальций | Ca | 40 |

| Кислород | O | 16 |

| Кремний | Si | 28 |

| Магний | Mg | 24 |

| Медь | Cu | 64 |

| Натрий | Na | 23 |

| Ртуть | Hg | 201 |

| Свинец | Pb | 207 |

| Сера | S | 32 |

| Серебро | Ag | 108 |

| Углерод | C | 12 |

| Фосфор | P | 31 |

| Хлор | Cl | 35,5 |

| Цинк | Zn | 65 |

[свернуть]

Если вы хотите познакомиться с названиями и символами всех химических элементов, загляните сюда. Там представлена периодическая система элементов, о которой вы узнаете позже.

Распространенность химических элементов в природе крайне неравномерна. Самый распространенный элемент в земной коре (слое толщиной 16 км) — кислород О. Его содержание составляет 49,13 % от общего числа атомов всех элементов. Доли остальных элементов показаны на рис. 28.

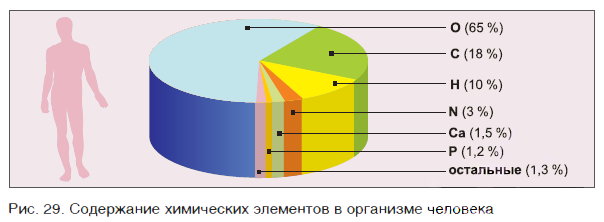

В организме человека на долю атомов кислорода приходится 65 % от массы тела, в то время как доля атомов углерода — 18 %, водорода — 10 %, азота — 3 % (см. рис. 29).

Во всей нашей Галактике почти 92 % от общего числа всех атомов приходится на долю водорода Н, 7,9 % — на долю гелия He и только 0,10 % — на атомы всех остальных элементов. Именно эти два самых легких элемента составляют основу звездной материи.

Краткие выводы урока:

- Атомы — мельчайшие, химически неделимые частицы.

- При химических реакциях атомы не исчезают и не возникают из ничего, а только переходят из одних веществ в другие.

- Каждый отдельный вид атомов называется химическим элементом. Он имеет свое название и обозначение — химический символ (знак).

- Атомы разных химических элементов различаются массой, размерами и строением.

Надеюсь урок 1 «Атомы и химические элементы» был понятным и познавательным. Если у вас возникли вопросы, пишите их в комментарии.

Занятие 4. Химические элементы. Знаки химических элементов. Относительная атомная масса.

Химический элемент — совокупность атомов одного вида.

Почему одинаковые атомы были названы именно так? Слово «элемент» (лат. elementum) использовалось еще

в античности (Цицероном, Овидием, Горацием) как часть чего-то (элемент речи,

элемент образования и т. п.). В древности было распространено изречение «Как

слова состоят из букв, так и тела — из элементов». Отсюда вероятное

происхождение этого слова: по названию ряда согласных букв в латинском

алфавите: l, m, n, t («el» — «em» — «en» — «tum»).

ХИМИЧЕСКИЙ ЯЗЫК

Человечество использует много разных языков.

Кроме естественных языков (японского, английского, русского – всего более 2,5

тысяч), существуют еще и искусственные языки, например, эсперанто. Среди

искусственных языков выделяются языки различных наук. Так, в химии используется

свой, химический язык. Химический язык – система условных обозначений и

понятий, предназначенная для краткой, ёмкой и наглядной записи и передачи

химической информации. Сообщение, написанное на большинстве естественных

языков, делится на предложения, предложения – на слова, а слова – на

буквы.

Мы с вами будем говорить особым, химическим

языком. В нем, как и в нашем родном, русском, мы выучим вначале буквы —

химические символы, затем научимся писать на их основе слова — формулы и далее,

с помощью последних, — предложения — уравнения химических реакций:

Болгарские просветители Кирилл и Мефодий

являются авторами славянской письменности-алфавита. А вот отцом химической

письменности является шведский ученый Й. Я. Берцелиус, который предложил в

качестве букв — символов химических элементов использовать начальные буквы их

латинских названий, или, если с этой буквы начинаются названия нескольких

элементов, то — добавлять к начальной букве еще одну из последующих букв

названия.

Химические знаки (символы химические) — буквенные обозначения химических элементов. Состоят из первой или

из первой и одной из следующих букв латинского названия элемента,напр., углерод

— С (Carboeum), кальций — Ca (Calcium), кадмий — Cd…

Символ химического элемента – это условное

обозначение химического элемента.

Историческая справка: Химики древнего мира и

средних веков применяли для обозначения веществ, химических операций и приборов

символические изображения, буквенные сокращения, а также сочетания тех и

других. Семь металлов древности изображали астрономическими знаками семи небесных

светил: Солнца ( ☉ , золото), Луны ( ☽ , серебро), Юпитера ( ♃ , олово),Венеры (♀, медь),

Сатурна ( ♄ , свинец), Меркурия ( ☿ , ртуть),Марса ( ♁ , железо).

|

|

рис. 1. 1 — олово, 2 — свинец, 3 — золото, 4 — |

Металлы, открытые в XV—XVIII веках, — висмут,

цинк,кобальт — обозначали первыми буквами их названий. Знак винного спирта

(лат. spiritus vini) составлен из букв S и V. Знаки крепкой водки (лат. aqua

fortis, азотная кислота) и золотой водки (лат. aqua regis, царская водка, смесь

соляной и азотной кислот) составлены из знака водыÑ и прописных букв F и R

соответственно. Знак стекла (лат. vitrum) образован из двух букв V —прямой и

перевёрнутой.

Попытки упорядочить старинные химические знаки продолжались до конца

XVIIIвека. В начале XIX века английский химик Дж. Дальтон предложил обозначать

атомы химических элементов кружками, внутри которых помещались точки, чёрточки,

начальные буквы английских названий металлов и др.

|

| Перечень символов химических элементов и их атомных весов Дж. Дальтона (1808) |

Химические знаки

Дальтона получили некоторое распространение в Великобритании и в Западной

Европе, но вскоре были вытеснены чисто буквенными знаками, которые шведский

химик Й. Я. Берцелиус предложил в 1814. Высказанные им принципы составления

химических знаков сохранили свою силу до настоящего времени. В России первое

печатное сообщение о химических знаках Берцелиуса сделал в 1824московский врач

И. Я. Зацепин.

ОТНОСИТЕЛЬНАЯ АТОМНАЯ МАССА

Историческая справка: Английский ученый Джон Дальтон (1766–1844) на своих лекциях демонстрировал студентам выточенные из дерева модели атомов, показывая, как они могут соединяться, образуя различные вещества. Когда одного из студентов спросили, что такое атомы, он ответил: «Атомы – это раскрашенные в разные цвета деревянные кубики, которые изобрел мистер Дальтон».

Конечно, Дальтон прославился не своими «кубиками» и даже не тем, что в двенадцатилетнем возрасте стал школьным учителем. С именем Дальтона связано возникновение современной атомистической теории. Впервые в истории науки он задумался о возможности измерения масс атомов и предложил для этого конкретные способы. Понятно, что непосредственно взвесить атомы невозможно. Дальтон рассуждал только о «соотношении весов мельчайших частиц газообразных и других тел», то есть об относительных их массах. И поныне, хотя масса любого атома в точности известна, ее никогда не выражают в граммах, так как это исключительно неудобно. Например, масса атома урана – самого тяжелого из существующих на Земле элементов – составляет всего 3,952·10–22г. Поэтому массу атомов выражают в относительных единицах, показывающих, во сколько раз масса атомов данного элемента больше массы атомов другого элемента, принятого в качестве стандарта. Фактически это и есть «соотношение весов» по Дальтону, т.е. относительная атомная масса. Массы атомов очень малы.

Абсолютные массы некоторых атомов:

m(C) =1,99268 ∙ 10-23 г

m(H) =1,67375 ∙ 10-24 г

m(O) =2,656812 ∙ 10-23 г

В настоящее время в физике и химии принята единая система измерения. Введена атомная единица массы (а.е.м.)

m(а.е.м.) = 1/12 m(12C) = 1,66057 ∙ 10-24 г.

Ar(H) = m(атома)/m (а.е.м.) = 1,67375 ∙ 10-24 г/1,66057 ∙ 10-24 г = 1,0079 а.е.м.

Ar – показывает, во сколько раз данный атом тяжелее 1/12 части атома 12С, это безразмерная величина.

Относительная атомная масса — это 1/12 массы атома углерода, масса которого равна 12 а.е.м.

Относительная атомная масса безразмерная величина!!!

Например, относительная атомная масса атома кислорода равна 15,994. Считать самим значения относительной атомной массы не всегда обязательно. Можно воспользоваться значениями, приведенными в периодической системы химических элементов Д. И. Менделеева. Записать это следует так:

Ar(O) = 16.

Всегда используем округлённое значение.

Исключение представляет относительная атомная масса атома хлора: Ar(Cl) = 35,5.

Связь между абсолютной и относительной массами атома представлена формулой:

m(атома) = Ar ∙ 1,66 ∙ 10 -27 кг

ТРЕНИРУЕМСЯ!!!

Распространённость элементов в

природе. Основную массу космического вещества составляют

Н и Не (99,9%).

Из 107 химических элементов только 89 обнаружены в природе, остальные, а

именно технеций (атомный номер 43), прометий (атомный номер 61), астат (атомный

номер 85), франций (атомный номер 87) и трансурановые элементы, получены

искусственно посредством ядерных реакций (ничтожные количества Te, Pm, Np, Fr

образуются при спонтанном делении урана и присутствуют в урановых рудах). В

доступной части Земли наиболее распространены 10 элементов с атомными номерами

в интервале от 8 до 26. В земной коре они содержатся в следующих относительных

количествах:

Перечисленные 10 элементов составляют 99,92% массы земной коры.

|

Элемент |

Атомный номер |

Содержание, % |

|

O |

8 |

47,00 |

|

Si |

14 |

29,50 |

|

Al |

13 |

8,05 |

|

Fe |

26 |

4,65 |

|

Ca |

20 |

3,30 |

|

Na |

11 |

2,50 |

|

K |

19 |

2,50 |

|

Mg |

12 |

1,87 |

|

Ti |

22 |

0,45 |

|

Mn |

25 |

0,10 |

«Химические элементы и их знаки»

Ключевые слова конспекта:Химические элементы, знаки химических элементов.

В химии очень важным является понятие «химический элемент» (слово «элемент» по-гречески означает «составная часть»). Чтобы понять его сущность, вспомните, чем различаются смеси и химические соединения.

Например, железо и сера свои свойства в смеси сохраняют. Поэтому можно утверждать, что смесь порошка железа с порошком серы состоит из двух простых веществ — железа и серы. Так как химическое соединение сульфид железа образуется из простых веществ — железа и серы, то хочется утверждать, что сульфид железа тоже состоит из железа и серы. Но познакомившись со свойствами сульфида железа, мы понимаем, что этого утверждать нельзя. Это сложное вещество, образовавшееся в результате химического взаимодействия, обладает совершенно другими свойствами, нежели исходные вещества. Потому что в состав сложных веществ входят не простые вещества, а атомы определённого вида.

ХИМИЧЕСКИЙ ЭЛЕМЕНТ — это определённый вид атомов.

Так, например, все атомы кислорода независимо от того, входят ли они в состав молекул кислорода или в состав молекул воды, — это химический элемент кислород. Все атомы водорода, железа, серы — это соответственно химические элементы водород, железо, сера и т. д.

В настоящее время известно 118 различных видов атомов, т. е. 118 химических элементов. Из атомов этого сравнительно небольшого числа элементов образуется огромное многообразие веществ. (Понятие «химический элемент» будет уточнено и расширено в дальнейших конспектах).

Пользуясь понятием «химический элемент», можно уточнить определения простых и сложных веществ: ПРОСТЫМИ называют вещества, которые состоят из атомов одного химического элемента. СЛОЖНЫМИ называют вещества, которые состоят из атомов разных химических элементов.

Следует различать понятия «простое вещество» и «химический элемент», хотя их названия в большинстве случаев совпадают. Поэтому каждый раз, когда мы встречаем слова «кислород», «водород», «железо», «сера» и т. д., нужно понимать, о чём идёт речь — о простом веществе или о химическом элементе. Если, например, говорят: «Растворённым в воде кислородом дышат рыбы», «Железо — это металл, который притягивается магнитом», это значит, что речь идёт о простых веществах — кислороде и железе. Если же говорят, что кислород или железо входит в состав какого-либо вещества, то имеют в виду кислород и железо как химические элементы.

Химические элементы и образуемые ими простые вещества можно разделить на две большие группы: металлы и неметаллы. Примерами металлов служат железо, алюминий, медь, золото, серебро и др. Металлы пластичны, имеют металлический блеск, хорошо проводят электрический ток. Примерами неметаллов служат сера, фосфор, водород, кислород, азот и др. Свойства неметаллов разнообразны.

Знаки химических элементов

Каждый химический элемент имеет своё название. Для упрощённого обозначения химических элементов используют химическую символику. Химический элемент обозначают начальной или начальной и одной из последующих букв латинского названия данного элемента. Так, водород (лат. hydrogenium — гидрогениум) обозначают буквой Н, ртуть (лат. hydrargyrum — гидраргирум) — буквами Hg и т. д. Предложил современную химическую символику шведский химик Й. Я. Берцелиус в 1814 году

Сокращённые буквенные обозначения химических элементов — это знаки (или символы) химических элементов. Химический символ (химический знак) обозначает один атом данного химического элемента.

Конспект урока «Химические элементы и их знаки».

Следующая тема: «Относительная атомная масса».