Время на прочтение

7 мин

Количество просмотров 23K

Туманность Андромеды, сфотографированная в Йеркской обсерватории около 1900 года. Для нас это очевидно галактика. Тогда её описали, как «массу светящегося газа» непонятного происхождения.

И что же особенного в этой дате? Новый год – просто случайное перелистывание календаря, но он может служить и моментом возвышения, обновления и пересмотра представлений. Так случилось и с одной из самых необычных дат в истории науки, 1 января 1925 года. Можно сказать, что тогда не случилось ничего примечательного, всего лишь обычный доклад на научной конференции. Или же его можно праздновать, как день рождения современной космологии, момент, когда человечество открыло Вселенную, как она есть.

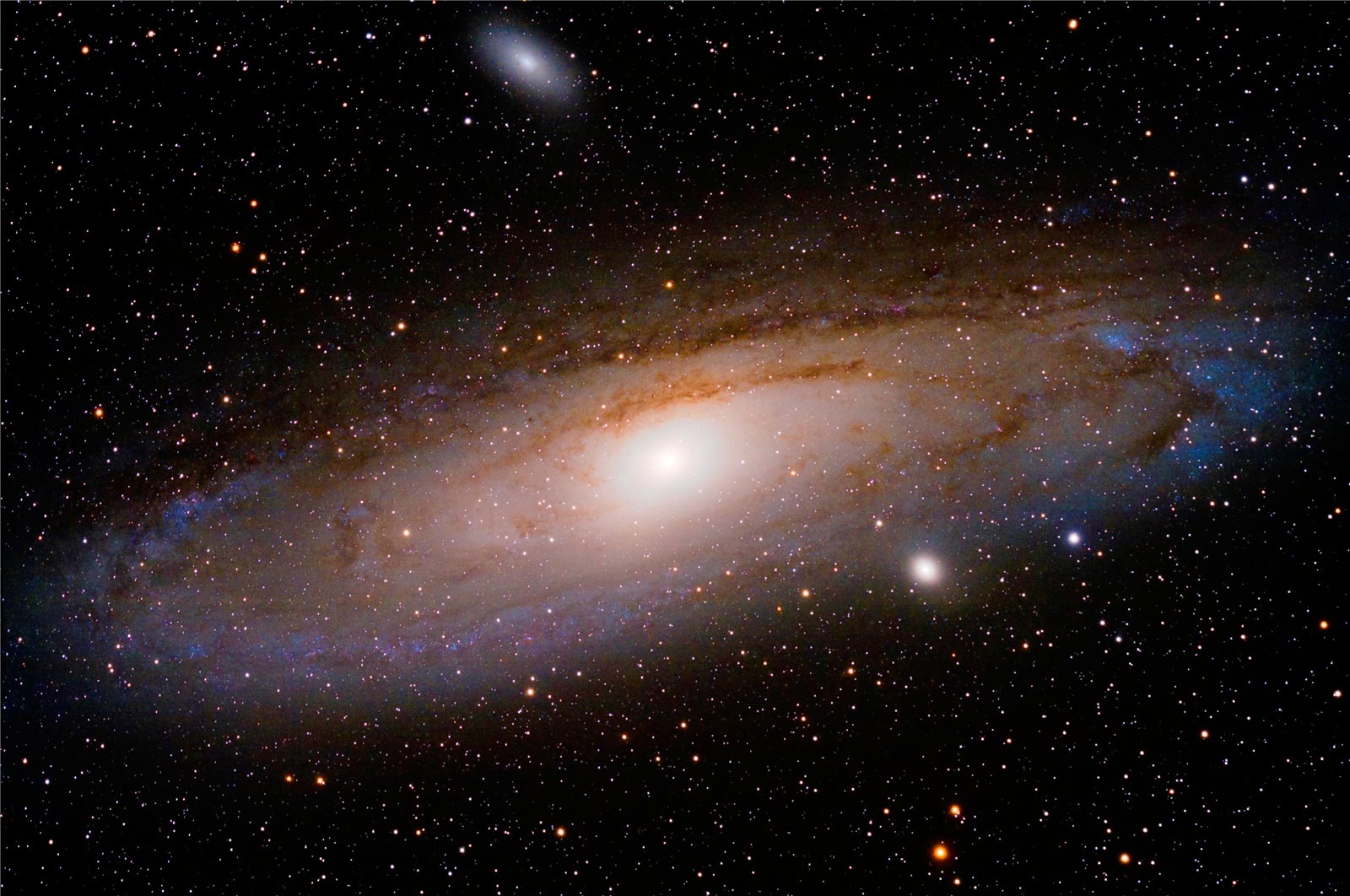

До того у астрономов был близорукий и ограниченный взгляд на реальность. Как это часто случается даже с самыми гениальными умами, они видели, но не понимали, на что смотрят. А ведь ключевой факт был прямо у них перед глазами. По всему небу были разбросанные интересные спиральные туманности, водовороты света, напоминавшие волчки. Самый известный из них, туманность Андромеды, был таким ярким, что его легко можно было увидеть ночью. Но значение этих вездесущих объектов оставалось загадкой.

Некоторые считали, что спиральные туманности были огромными и отдалёнными звёздными системами, «островными вселенными», сравнимыми с нашей галактикой Млечный путь. Многие другие были уверены, что это всего лишь небольшие, близко расположенные облака газа. С их точки зрения, другие галактики, если они и существуют, были не видны, и находились далеко в глубинах космоса. А может, и не было никаких других галактик, а был лишь один Млечный путь – одна система, определявшая Вселенную. Споры между двумя сторонами были настолько жаркими, что привели к знаменитому Большому спору 1920 года, закончившемуся неудовлетворительной ничьёй.

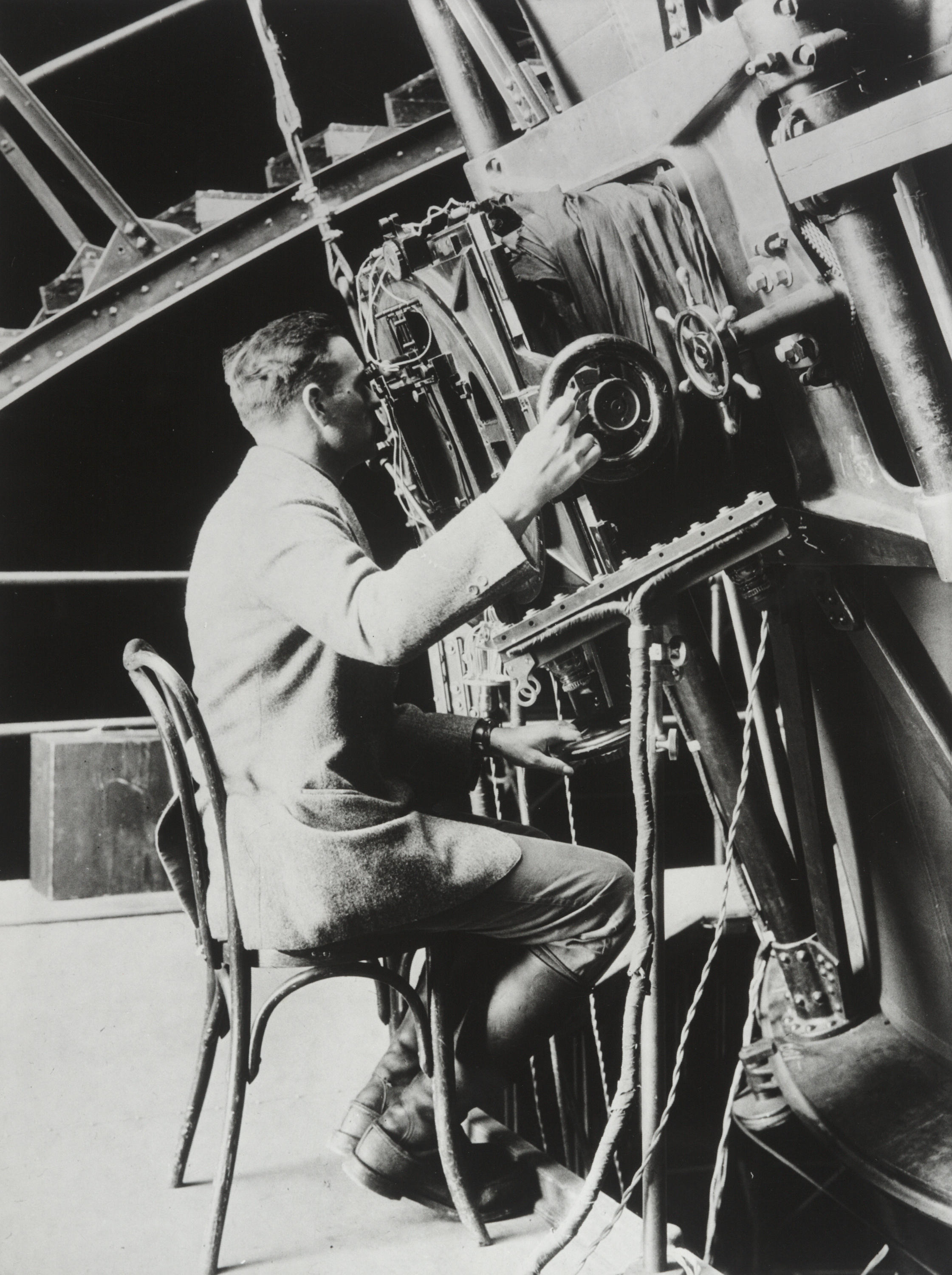

Правильное представление о нашем месте во Вселенной появилось всего через несколько лет, в работе одного из самых известных астрономов: Эдвина Пауэлла Хаббла. С 1919 года Хаббл стал одним из самых терпеливых и скрупулёзных наблюдателей в обсерватории Маунт-Вилсон в Калифорнии. А сама обсерватория стала главным авангардом астрономических исследований, домом недавно созданного 100-дюймового телескопа Хукера – тогда это был крупнейший телескоп мира. Это была идеальная комбинация из нужного наблюдателя в нужном месте в нужное время.

Хабблу очень помогло предыдущее исследование Весто Мелвина Слайфера из обсерватории Лоуэлла, одного из невоспетых героев современной космологии. Слайфер обнаружил, что многие из спиральных туманностей двигаются с огромными скоростями, быстрее, чем любые из известных звёзд, и что двигаются они в основном от нас. Для Слайфера это открытие стало убедительным доказательством независимости этих систем, влекомых неизвестными механизмами, работающими вне Млечного пути. Но у Слайфера недоставало необходимых ресурсов для доказательства своей интерпретации. Ему требовался гигантский телескоп, такой, каким управлял Хаббл на Маунт-Вилсон. Именно там наша история переключается на верхнюю передачу.

Эдвин Хаббл за управлением 100-дюймовым телескопом в Маунт-Вилсон, около 1922 года

Хаббл всегда осторожно относился к теориям и интерпретациям. Он сконцентрировал своё научное внимание на спиральных туманностях без упора на необходимость доказательства теории «островных вселенных». Он предпочитал подождать до тех пор, когда он сможет представить однозначное подтверждение или опровержение этой теории – в зависимости от того, на что укажут доказательства.

В 1922 году появился ещё один важный кусочек головоломки. В том году шведский астроном Кнут Эмиль Лундмарк увидел то, что он посчитал отдельными звёздами в рукавах спиральной туманности М33. Вскоре после этого Джон Дункан из обсерватории Маунт-Вилсон заметил точки света, затухающие и разгорающиеся в той же самой туманности. Могли ли это быть переменные звёзды, похожие на те, что существуют в Млечном пути, но гораздо более тусклые из-за огромного расстояния до них?

Чувствуя, что ответ близок, Хаббл удвоил усилия. Он проводил ночи в своём любимом деревянном кресле, управляя стальной монтировкой хукеровского телескопа для устранения эффектов от вращения Земли. Попытка увенчалась успехом в виде детальных изображений туманности Андромеды с большой выдержкой. Пятнистый свет туманности начал превращаться во множество ярких точек, которые выглядели не как газ, а как гигантский рой звёзд.

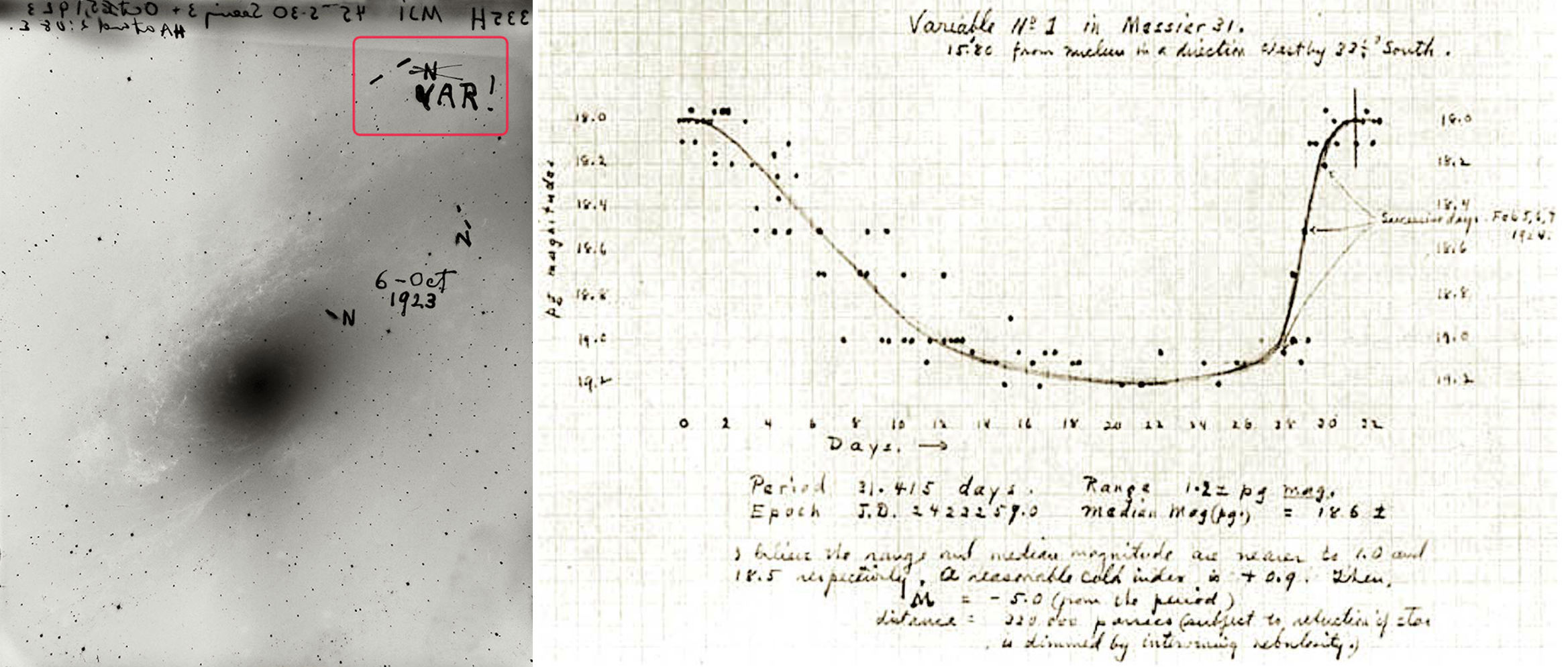

Окончательное доказательство появилось в октябре 1923 года, когда Хаббл заметил характерное мерцание отдельной переменной звезды из класса цефеид в одном из рукавов Андромеды. Видимая яркость такой звезды меняется предсказуемо и периодически, а её собственная яркость зависит от периода колебаний. Просто замерив 31-дневный цикл мерцания звезды, Хаббл мог подсчитать расстояние до неё. По его расчётам получалось 930 000 световых лет – меньше половины сегодняшней оценки, но для своего времени всё равно шокирующая цифра. Это расстояние располагало Андромеду, одну из ярчайших и, возможно, ближайших спиральных туманностей, далеко за пределами Млечного пути.

В принципе, именно тогда и разрешился Большой спор. Спиральные туманности были другими галактиками, а наш Млечный путь был всего лишь одним из аванпостов ошеломляюще обширной Вселенной. Но история этим вовсе не закончилась.

С присущей ему осторожностью Хаббл начал искать больше доказательств. В следующем феврале он открыл, возможно, ещё одну цефеиду в Андромеде, несколько цефеид в М33, и, возможно, ещё в трёх других туманностях. И когда сомнений не оставалось, он написал об этой новости своему давнему сопернику, Харлоу Шейпли – ведущему стороннику идеи о небольших и недалеко расположенных спиральных туманностях – с целью поддразнить его. «Вам будет интересно узнать, что я нашёл цефеиду в туманности Андромеды», – начиналось письмо.

Шейпли не нужно было читать дальше, чтобы понять важность слов Хаббла. «Это письмо разрушило мою вселенную», — сердито поведал Шейпли Сесилии Хелене Пейн-Гапошкиной [Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin], кандидату в доктора в Гарварде, оказавшуюся в лаборатории в момент прибытия послания от Хаббла. Пэйн-Гапошкина была ещё одной ключевой фигурой для современной астрофизики. По удивительному совпадению, её новаторская работа по звёздному спектру была завершена 1 января 1925 года!

Несмотря на очевидное радостное волнение по поводу открытий в Андромеде, Хаббл всё ещё колебался с публикацией результатов. При всей показной уверенности, он ужасно волновался по поводу громкого и преждевременного объявления об открытии. Каждый раз, идя с собрания на формальный ужин в 5 вечера в Монастырь, жилые помещения Маунт-Вилсон, Хаббл встречался со своими коллегами-астрономами. Не все они принимали существование других галактик. Будучи тщеславным и тщательно следящим за своей репутацией учёным, Хаббл опасался выглядеть дураком.

Адриан ван Маанен, весёлый и симпатичный всем нидерландский астроном на Маунт-Вилсон, энергично доказывал противоположную точку зрения. Он был убеждён, что наблюдал вращение некоторых из спиральных туманностей, что было возможно, только если те были достаточно маленькими и были расположены достаточно близко. Хаббла волновало наличие сомневающегося учёного в своих рядах, и держался, пока не приобрёл абсолютной уверенности в результатах. Ван Маанен так и не понял, где ошибался, и отказался признать ошибку. Хаббл в итоге пересмотрел фотопластинки коллеги, и объявил, что «найденные ранее вращения оказались результатами скрытых систематических ошибок, и не указывали на движение туманностей, реальное или кажущееся». С академической точки зрения это был весьма резкий упрёк.

Единственная переменная звезда, замеченная Хабблом в туманности Андромеда, поменяла всё наше представление о размерах космоса. Слева – изображение, помогшее открытию. Справа – кривая яркости звезды.

Информация об открытии Хаббла неизбежно просочилась в прессу. В результате первым публичным объявлением об астрономическом прорыве стала небольшая заметка, прошедшая в The New York Times 23 ноября 1924 года. Самое важное за последние три столетия открытие, связанное с космосом, вышло в виде одной новости из целой кучи!

И всё же Хаббл удерживался от формальной публикации. Видный астроном Генри Норрис Рассел уговаривал его представить свои открытия на встрече в столице Американской ассоциации научных достижений, предлагавшей за лучшую работу приз в $1000. Когда Хаббл так и не предложил свою работу, Рассел хмыкнул: «Ну и осёл же он. Ему в руки идёт лёгкая тысяча долларов, а он отказывается её брать». А потом Рассел открыл почту, и обнаружил, что работа от Хаббла только что пришла.

И только теперь мы подходим к ошеломляющему публичному объявлению. 1 января 1925 года Хаббл находился в изоляции на Маунт-Вилсон, а Рассел читал его революционную работу о существовании других галактик перед полной энтузиазма толпой. Хабблу досталась часть приза за лучшую работу. Она завершила Большой спор, и не только. Она резко увеличила размер известной вселенной в 100 000 раз. Она подготовила почву для открытия расширяющейся вселенной, и, как следствие, изначального Большого взрыва (на который уже намекали скорости, записанные Слайфером). Если и можно назначить какую-либо дату днём рождения современной космологии, то это её.

Как ни странно, именно Шэйпли, а не Хаббл, предложил астрономам адаптировать свою номенклатуру к новой реальности и называть внешние звёздные системы «галактиками». Хаббл всё ещё пользовался консервативными взглядами на мир, опровергнутый им же. Он также естественно предпочитал не соглашаться с любыми идеями, поданными его соперником, Шэйпли. Поэтому Эдвин Хаббл, человек, доказавший, что Млечный путь – лишь одна из неисчислимого множества галактик, так и не перестал называть эти объекты «экстра-галактическими туманностями».

Наблюдая за циклическими колебаниями яркости цефеид в Андромеде, Хаббл расширил возможности человеческого разума ещё одним способом. Он избавил нас от волнений по поводу того, что крайне удалённые от нас звёзды могут вести себя по-другому, нежели те, что находятся по соседству с нами. Теперь, когда учёные могли исследовать звёзды в других галактиках, они могли определить постоянство Вселенной в пространстве и времени.

По современным подсчётам, галактика Андромеда находится в 2,5 млн световых годах от нас, то есть, видимый нами свет стартовал 2,5 млн лет назад. Получается, что мы видим звёзды этой галактики не только удалёнными на 2,5 млн световых лет, но и живущими в 2,5 млн лет в прошлом. Тем не менее, они выглядят похожими на ближайшие к нам звёзды. И когда Эдвин Хаббл и другие астрономы заглядывали ещё дальше, они добавляли всё больше доказательств пространственного и временного единообразия. Во всём пространстве и все времена атомы, судя по всему, испускают тот же самый свет, и переменные звёзды подчиняются тем же самым физическим законам.

Это постоянство природы придало убедительности поискам одного набора правил, действующих по всему космосу. Или, как сказал бы Альберт Эйнштейн, показало, что Бог не меняет правила существования космоса. Это был чертовски неплохой подарок на день рождения для человеческого разума.

| Andromeda Galaxy | |

|---|---|

A visible light image of the Andromeda Galaxy. Messier 32 is to the left of the galactic nucleus and Messier 110 at the bottom right. |

|

| Observation data (J2000 epoch) | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Constellation | Andromeda |

| Right ascension | 00h 42m 44.3s[1] |

| Declination | +41° 16′ 9″[1] |

| Redshift | z = −0.001004 (minus sign indicates blueshift)[1] |

| Helio radial velocity | −301 ± 1 km/s[2] |

| Distance | 765 kpc (2.50 Mly)[3] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 3.44[4][5] |

| Absolute magnitude (V) | −21.5[a][6] |

| Characteristics | |

| Type | SA(s)b[1] |

| Mass | (1.5±0.5)×1012[7] M☉ |

| Number of stars | ~1 trillion (1012)[10] |

| Size | 46.56 kpc (152,000 ly) (diameter; 25.0 mag/arcsec2 B-band isophote)[1][8][b] |

| Apparent size (V) | 3.167° × 1°[1] |

| Other designations | |

| M31, NGC 224, UGC 454, PGC 2557, 2C 56 (Core),[1] CGCG 535-17, MCG +07-02-016, IRAS 00400+4059, 2MASX J00424433+4116074, GC 116, h 50, Bode 3, Flamsteed 58, Hevelius 32, Ha 3.3, IRC +40013 |

The Andromeda Galaxy (also known as Messier 31, M31, NGC 224 and originally the Andromeda Nebula) is a barred spiral galaxy and is the closest major galaxy to the Milky Way, where the Solar System resides. It has a diameter of about 46.56 kiloparsecs (152,000 light-years)[8] and is approximately 765 kpc (2.5 million light-years) from Earth. The galaxy’s name stems from the area of Earth’s sky in which it appears, the constellation of Andromeda, which itself is named after the princess who was the wife of Perseus in Greek mythology.

The virial mass of the Andromeda Galaxy is of the same order of magnitude as that of the Milky Way, at 1 trillion solar masses (2.0×1042 kilograms). The mass of either galaxy is difficult to estimate with any accuracy, but it was long thought that the Andromeda Galaxy was more massive than the Milky Way by a margin of some 25% to 50%. This has been called into question by early 21st-century studies indicating a possibly lower mass for the Andromeda Galaxy[11]

and a higher mass for the Milky Way.[12][13] The Andromeda Galaxy has a diameter of about 46.56 kpc (152,000 ly), making it the largest member of the Local Group in terms of extension.

The Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies are expected to collide in around 4–5 billion years,[14] merging to potentially form a giant elliptical galaxy[15] or a large lenticular galaxy.[16]

With an apparent magnitude of 3.4, the Andromeda Galaxy is among the brightest of the Messier objects,[17] and is visible to the naked eye from Earth on moonless nights,[18] even when viewed from areas with moderate light pollution.

Observation history[edit]

The earliest known photograph of the Great Andromeda «Nebula» (with M110 to lower left), by Isaac Roberts, December 29, 1888.

The Andromeda Galaxy has been visible to the naked eye, given dark skies, throughout history; as such, it cannot be said to have been «discovered» by any one individual. Around the year 964, the Persian astronomer Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi was the first to formally describe the Andromeda Galaxy. He referred to it in his Book of Fixed Stars as a «nebulous smear» or «small cloud».[19][20]

Star charts of that period labeled it as the Little Cloud.[21] In 1612, the German astronomer Simon Marius gave an early description of the Andromeda Galaxy based on telescopic observations.[22] Pierre Louis Maupertuis conjectured in 1745 that the blurry spot was an island universe.[23] In 1764, Charles Messier cataloged Andromeda as object M31 and incorrectly credited Marius as the discoverer despite its being visible to the naked eye. In 1785, the astronomer William Herschel noted a faint reddish hue in the core region of Andromeda. He believed Andromeda to be the nearest of all the «great nebulae», and based on the color and magnitude of the nebula, he incorrectly guessed that it was no more than 2,000 times the distance of Sirius, or roughly 18,000 ly (5.5 kpc).[24] In 1850, William Parsons, 3rd Earl of Rosse made the first drawing of Andromeda’s spiral structure.

In 1864 William Huggins noted that the spectrum of Andromeda differed from that of a gaseous nebula.[25] The spectrum of Andromeda displays a continuum of frequencies, superimposed with dark absorption lines that help identify the chemical composition of an object. Andromeda’s spectrum is very similar to the spectra of individual stars, and from this, it was deduced that Andromeda has a stellar nature. In 1885, a supernova (known as S Andromedae) was seen in Andromeda, the first and so far only one observed in that galaxy. At the time it was called «Nova 1885»[26] – the difference between «novae» in the modern sense and supernovae was not yet known. Andromeda was considered to be a nearby object, and it was not realized that the «nova» was much brighter than ordinary novae.

In 1888, Isaac Roberts took one of the first photographs of Andromeda, which was still commonly thought to be a nebula within our galaxy. Roberts mistook Andromeda and similar «spiral nebulae» as star systems being formed.[27][28]

In 1912, Vesto Slipher used spectroscopy to measure the radial velocity of Andromeda with respect to the Solar System—the largest velocity yet measured, at 300 km/s (190 mi/s).[29]

«Island universes» hypothesis[edit]

Location of the Andromeda Galaxy (M31) in the Andromeda constellation.

As early as 1755 the German philosopher Immanuel Kant proposed the hypothesis that the Milky Way is only one of many galaxies, in his book Universal Natural History and Theory of the Heavens. Arguing that a structure like the Milky Way would look like a circular nebula viewed from above and like an elliptical if viewed from an angle, he concluded that the observed elliptical nebulae like Andromeda, which could not be explained otherwise at the time, were indeed galaxies similar to the Milky Way.

In 1917, Heber Curtis observed a nova within Andromeda. Searching the photographic record, 11 more novae were discovered. Curtis noticed that these novae were, on average, 10 magnitudes fainter than those that occurred elsewhere in the sky. As a result, he was able to come up with a distance estimate of 500,000 ly (3.2×1010 AU). Although this estimate is about fivefold lower than the best estimates now available, it was the first known estimate of the distance to Andromeda that was correct to the order of magnitude (i.e which was correct to within a factor of ten of current high-accuracy estimates, which place the distance around 2.5 million light-years[2][30][6][31]). Curtis became a proponent of the so-called «island universes» hypothesis: that spiral nebulae were actually independent galaxies.[32]

In 1920, the Great Debate between Harlow Shapley and Curtis took place concerning the nature of the Milky Way, spiral nebulae, and the dimensions of the universe. To support his claim of the Great Andromeda Nebula being, in fact, an external galaxy, Curtis also noted the appearance of dark lanes within Andromeda which resembled the dust clouds in our own galaxy, as well as historical observations of Andromeda Galaxy’s significant Doppler shift. In 1922 Ernst Öpik presented a method to estimate the distance of Andromeda using the measured velocities of its stars. His result placed the Andromeda Nebula far outside our galaxy at a distance of about 450 kpc (1,500 kly).[33] Edwin Hubble settled the debate in 1925 when he identified extragalactic Cepheid variable stars for the first time on astronomical photos of Andromeda. These were made using the 100-inch (2.5 m) Hooker telescope, and they enabled the distance of the Great Andromeda Nebula to be determined. His measurement demonstrated conclusively that this feature was not a cluster of stars and gas within our own galaxy, but an entirely separate galaxy located a significant distance from the Milky Way.[34]

In 1943, Walter Baade was the first person to resolve stars in the central region of the Andromeda Galaxy. Baade identified two distinct populations of stars based on their metallicity, naming the young, high-velocity stars in the disk Type I and the older, red stars in the bulge Type II. This nomenclature was subsequently adopted for stars within the Milky Way, and elsewhere. (The existence of two distinct populations had been noted earlier by Jan Oort.)[35] Baade also discovered that there were two types of Cepheid variable stars, which resulted in a doubling of the distance estimate to Andromeda, as well as the remainder of the universe.[36]

In 1950, radio emission from the Andromeda Galaxy was detected by Hanbury Brown and Cyril Hazard at Jodrell Bank Observatory.[37][38] The first radio maps of the galaxy were made in the 1950s by John Baldwin and collaborators at the Cambridge Radio Astronomy Group.[39] The core of the Andromeda Galaxy is called 2C 56 in the 2C radio astronomy catalog. In 2009, a technique called microlensing—a phenomenon caused by the deflection of light by a massive object—may have led to the first discovery of a planet in the Andromeda Galaxy.[40]

Observations of linearly polarized radio emission with the Westerbork Synthesis Radio Telescope, the Effelsberg 100-m Radio Telescope, and the Very Large Array revealed ordered magnetic fields aligned along the «10-kpc ring» of gas and star formation.[41] The total magnetic field has a strength of about 0.5 nT, of which 0.3 nT are ordered.

General[edit]

The estimated distance of the Andromeda Galaxy from our own was doubled in 1953 when it was discovered that there is another, dimmer type of Cepheid variable star. In the 1990s, measurements of both standard red giants as well as red clump stars from the Hipparcos satellite measurements were used to calibrate the Cepheid distances.[42][43]

Formation and history[edit]

Processed image of the Andromeda Galaxy, with enhancement of H-alpha to highlight its star-forming regions.

The Andromeda Galaxy was formed roughly 10 billion years ago from the collision and subsequent merger of smaller protogalaxies.[44]

This violent collision formed most of the galaxy’s (metal-rich) galactic halo and extended disk. During this epoch, its rate of star formation would have been very high, to the point of becoming a luminous infrared galaxy for roughly 100 million years. Andromeda and the Triangulum Galaxy (M33) had a very close passage 2–4 billion years ago. This event produced high rates of star formation across the Andromeda Galaxy’s disk—even some globular clusters—and disturbed M33’s outer disk.

Over the past 2 billion years, star formation throughout Andromeda’s disk is thought to have decreased to the point of near-inactivity. There have been interactions with satellite galaxies such as M32, M110, or others that have already been absorbed by the Andromeda Galaxy. These interactions have formed structures like Andromeda’s Giant Stellar Stream. A galactic merger roughly 100 million years ago is believed to be responsible for a counter-rotating disk of gas found in the center of Andromeda as well as the presence there of a relatively young (100 million years old) stellar population.[44]

Distance estimate[edit]

Illustration showing both the size of each galaxy and the distance between the two galaxies, to scale.

At least four distinct techniques have been used to estimate distances from Earth to the Andromeda Galaxy. In 2003, using the infrared surface brightness fluctuations (I-SBF) and adjusting for the new period-luminosity value and a metallicity correction of −0.2 mag dex−1 in (O/H), an estimate of 2.57 ± 0.06 million light-years (1.625×1011 ± 3.8×109 astronomical units) was derived. A 2004 Cepheid variable method estimated the distance to be 2.51 ± 0.13 million light-years (770 ± 40 kpc).[2][30] In 2005, an eclipsing binary star was discovered in the Andromeda Galaxy. The binary[c] is two hot blue stars of types O and B. By studying the eclipses of the stars, astronomers were able to measure their sizes. Knowing the sizes and temperatures of the stars, they were able to measure their absolute magnitude. When the visual and absolute magnitudes are known, the distance to the star can be calculated. The stars lie at a distance of 2.52×106 ± 0.14×106 ly (1.594×1011 ± 8.9×109 AU) and the whole Andromeda Galaxy at about 2.5×106 ly (1.6×1011 AU).[6] This new value is in excellent agreement with the previous, independent Cepheid-based distance value. The TRGB method was also used in 2005 giving a distance of 2.56×106 ± 0.08×106 ly (1.619×1011 ± 5.1×109 AU).[31] Averaged together, these distance estimates give a value of 2.54×106 ± 0.11×106 ly (1.606×1011 ± 7.0×109 AU).[d]

Mass estimates[edit]

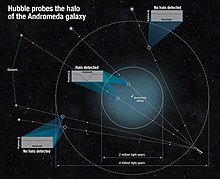

Giant halo around Andromeda Galaxy[45]

Until 2018, mass estimates for the Andromeda Galaxy’s halo (including dark matter) gave a value of approximately 1.5×1012 M☉,[46] compared to 8×1011 M☉ for the Milky Way. This contradicted earlier measurements that seemed to indicate that the Andromeda Galaxy and Milky Way are almost equal in mass.

In 2018, the equality of mass was re-established by radio results as approximately 8×1011 M☉.[47][48][49][50] In 2006, the Andromeda Galaxy’s spheroid was determined to have a higher stellar density than that of the Milky Way,[51] and its galactic stellar disk was estimated at about twice the diameter of that of the Milky Way.[9] The total mass of the Andromeda Galaxy is estimated to be between 8×1011 M☉[47] and 1.1×1012 M☉.[52][53] The stellar mass of M31 is 10–15×1010 M☉, with 30% of that mass in the central bulge, 56% in the disk, and the remaining 14% in the stellar halo.[54] The radio results (similar mass to the Milky Way Galaxy) should be taken as likeliest as of 2018, although clearly, this matter is still under active investigation by several research groups worldwide.

As of 2019, current calculations based on escape velocity and dynamical mass measurements put the Andromeda Galaxy at 0.8×1012 M☉,[55] which is only half of the Milky Way’s newer mass, calculated in 2019 at 1.5×1012 M☉.[56][57][58]

In addition to stars, the Andromeda Galaxy’s interstellar medium contains at least 7.2×109 M☉[59] in the form of neutral hydrogen, at least 3.4×108 M☉ as molecular hydrogen (within its innermost 10 kiloparsecs), and 5.4×107 M☉ of dust.[60]

The Andromeda Galaxy is surrounded by a massive halo of hot gas that is estimated to contain half the mass of the stars in the galaxy. The nearly invisible halo stretches about a million light-years from its host galaxy, halfway to our Milky Way Galaxy. Simulations of galaxies indicate the halo formed at the same time as the Andromeda Galaxy. The halo is enriched in elements heavier than hydrogen and helium, formed from supernovae, and its properties are those expected for a galaxy that lies in the «green valley» of the Galaxy color–magnitude diagram (see below). Supernovae erupt in the Andromeda Galaxy’s star-filled disk and eject these heavier elements into space. Over the Andromeda Galaxy’s lifetime, nearly half of the heavy elements made by its stars have been ejected far beyond the galaxy’s 200,000-light-year-diameter stellar disk.[61][62][63][64]

Luminosity estimates[edit]

Compared to the Milky Way, the Andromeda Galaxy appears to have predominantly older stars with ages >7×109 years.[54][clarification needed] The estimated luminosity of the Andromeda Galaxy, ~2.6×1010 L☉, is about 25% higher than that of our own galaxy.[65][66] However, the galaxy has a high inclination as seen from Earth, and its interstellar dust absorbs an unknown amount of light, so it is difficult to estimate its actual brightness and other authors have given other values for the luminosity of the Andromeda Galaxy (some authors even propose it is the second-brightest galaxy within a radius of 10 megaparsecs of the Milky Way, after the Sombrero Galaxy,[67] with an absolute magnitude of around −22.21[e] or close[68]).

An estimation done with the help of Spitzer Space Telescope published in 2010 suggests an absolute magnitude (in the blue) of −20.89 (that with a color index of +0.63 translates to an absolute visual magnitude of −21.52,[a] compared to −20.9 for the Milky Way), and a total luminosity in that wavelength of 3.64×1010 L☉.[69]

The rate of star formation in the Milky Way is much higher, with the Andromeda Galaxy producing only about one solar mass per year compared to 3–5 solar masses for the Milky Way. The rate of novae in the Milky Way is also double that of the Andromeda Galaxy.[70] This suggests that the latter once experienced a great star formation phase, but is now in a relative state of quiescence, whereas the Milky Way is experiencing more active star formation.[65] Should this continue, the luminosity of the Milky Way may eventually overtake that of the Andromeda Galaxy.

According to recent studies, the Andromeda Galaxy lies in what in the Galaxy color–magnitude diagram is known as the «green valley», a region populated by galaxies like the Milky Way in transition from the «blue cloud» (galaxies actively forming new stars) to the «red sequence» (galaxies that lack star formation). Star formation activity in green valley galaxies is slowing as they run out of star-forming gas in the interstellar medium. In simulated galaxies with similar properties to the Andromeda Galaxy, star formation is expected to extinguish within about five billion years, even accounting for the expected, short-term increase in the rate of star formation due to the collision between the Andromeda Galaxy and the Milky Way.[71]

Structure[edit]

A panorama of the Andromeda Galaxy’s nucleus and stars

A narrated tour of the Andromeda Galaxy, made by NASA’s Swift satellite team

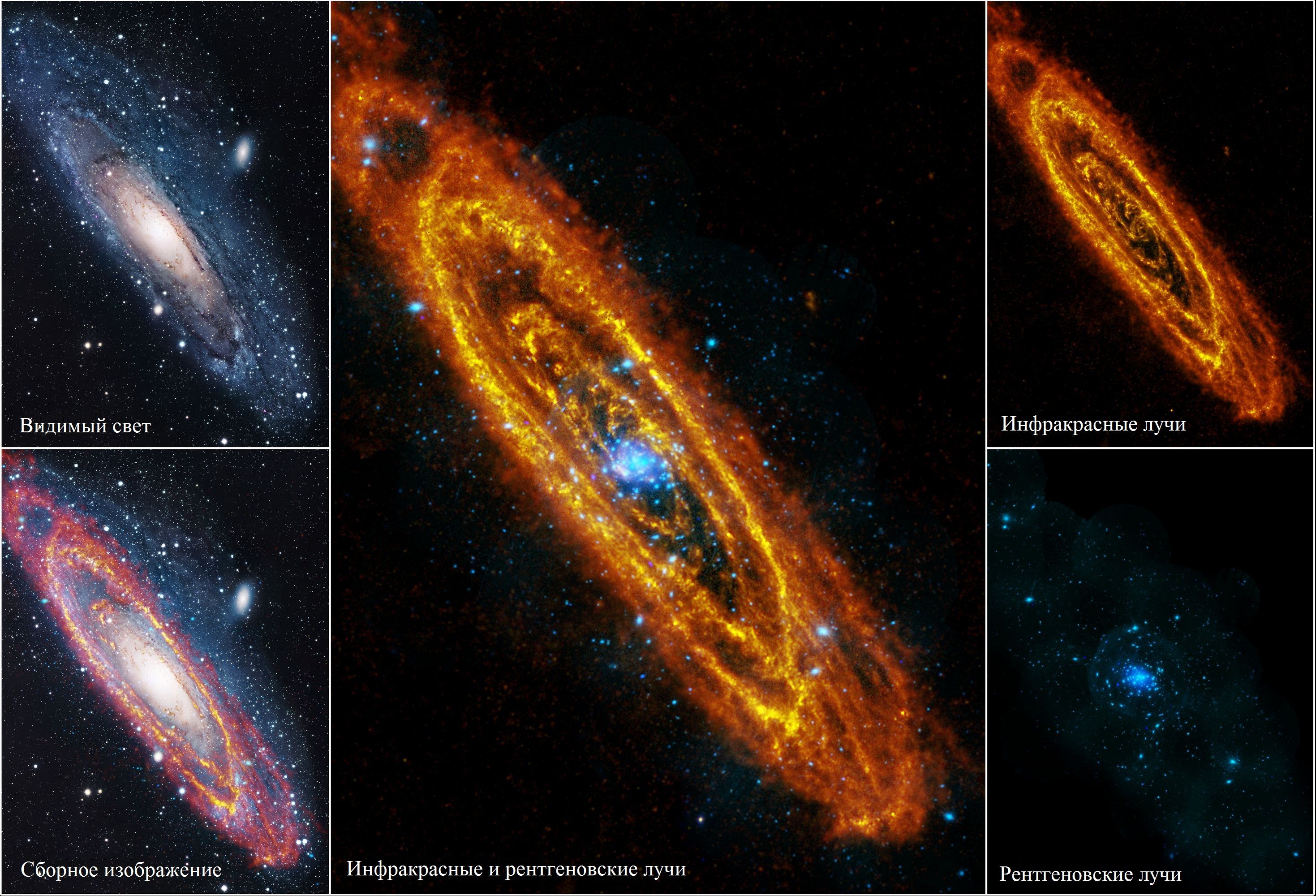

Based on its appearance in visible light, the Andromeda Galaxy is classified as an SA(s)b galaxy in the de Vaucouleurs–Sandage extended classification system of spiral galaxies.[1] However, infrared data from the 2MASS survey and the Spitzer Space Telescope showed that Andromeda is actually a barred spiral galaxy, like the Milky Way, with Andromeda’s bar major axis oriented 55 degrees anti-clockwise from the disc major axis.[72]

There are various methods used in astronomy in defining the size of a galaxy, and each method can yield different results concerning one another. The most commonly employed is the D25 standard — the isophote where the photometric brightness of a galaxy in the B-band (445 nm wavelength of light, in the blue part of the visible spectrum) reaches 25 mag/arcsec2.[73] The Third Reference Catalogue of Bright Galaxies (RC3) used this standard for Andromeda in 1991, yielding an isophotal diameter of 46.56 kiloparsecs (152,000 light-years) at a distance of 2.5 million light-years.[8] An earlier estimate from 1981 gave a diameter for Andromeda at 54 kiloparsecs (176,000 light-years).[74]

A study in 2005 by the Keck telescopes shows the existence of a tenuous sprinkle of stars, or galactic halo, extending outward from the galaxy.[9] The stars in this halo behave differently from the ones in Andromeda’s main galactic disc, where they show rather disorganized orbital motions as opposed to the stars in the main disc having more orderly orbits and uniform velocities of 200 km/s.[9] This diffuse halo extends outwards away from Andromeda’s main disc with the diameter of 67.45 kiloparsecs (220,000 light-years).[9]

The galaxy is inclined an estimated 77° relative to Earth (where an angle of 90° would be edge-on). Analysis of the cross-sectional shape of the galaxy appears to demonstrate a pronounced, S-shaped warp, rather than just a flat disk.[75] A possible cause of such a warp could be gravitational interaction with the satellite galaxies near the Andromeda Galaxy. The Galaxy M33 could be responsible for some warp in Andromeda’s arms, though more precise distances and radial velocities are required.

Spectroscopic studies have provided detailed measurements of the rotational velocity of the Andromeda Galaxy as a function of radial distance from the core. The rotational velocity has a maximum value of 225 km/s (140 mi/s) at 1,300 ly (82,000,000 AU) from the core, and it has its minimum possibly as low as 50 km/s (31 mi/s) at 7,000 ly (440,000,000 AU) from the core. Further out, rotational velocity rises out to a radius of 33,000 ly (2.1×109 AU), where it reaches a peak of 250 km/s (160 mi/s). The velocities slowly decline beyond that distance, dropping to around 200 km/s (120 mi/s) at 80,000 ly (5.1×109 AU). These velocity measurements imply a concentrated mass of about 6×109 M☉ in the nucleus. The total mass of the galaxy increases linearly out to 45,000 ly (2.8×109 AU), then more slowly beyond that radius.[76]

The spiral arms of the Andromeda Galaxy are outlined by a series of HII regions, first studied in great detail by Walter Baade and described by him as resembling «beads on a string». His studies show two spiral arms that appear to be tightly wound, although they are more widely spaced than in our galaxy.[77] His descriptions of the spiral structure, as each arm crosses the major axis of the Andromeda Galaxy, are as follows[78]§pp1062[79]§pp92:

| Arms (N=cross M31’s major axis at north, S=cross M31’s major axis at south) | Distance from center (arcminutes) (N*/S*) | Distance from the center (kpc) (N*/S*) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| N1/S1 | 3.4/1.7 | 0.7/0.4 | Dust arms with no OB associations of HII regions. |

| N2/S2 | 8.0/10.0 | 1.7/2.1 | Dust arms with some OB associations. |

| N3/S3 | 25/30 | 5.3/6.3 | As per N2/S2, but with some HII regions too. |

| N4/S4 | 50/47 | 11/9.9 | Large numbers of OB associations, HII regions, and little dust. |

| N5/S5 | 70/66 | 15/14 | As per N4/S4 but much fainter. |

| N6/S6 | 91/95 | 19/20 | Loose OB associations. No dust is visible. |

| N7/S7 | 110/116 | 23/24 | As per N6/S6 but fainter and inconspicuous. |

Since the Andromeda Galaxy is seen close to edge-on, it is difficult to study its spiral structure. Rectified images of the galaxy seem to show a fairly normal spiral galaxy, exhibiting two continuous trailing arms that are separated from each other by a minimum of about 13,000 ly (820,000,000 AU) and that can be followed outward from a distance of roughly 1,600 ly (100,000,000 AU) from the core. Alternative spiral structures have been proposed such as a single spiral arm[80] or a flocculent[81] pattern of long, filamentary, and thick spiral arms.[1][82]

The most likely cause of the distortions of the spiral pattern is thought to be interaction with galaxy satellites M32 and M110.[83] This can be seen by the displacement of the neutral hydrogen clouds from the stars.[84]

In 1998, images from the European Space Agency’s Infrared Space Observatory demonstrated that the overall form of the Andromeda Galaxy may be transitioning into a ring galaxy. The gas and dust within the galaxy are generally formed into several overlapping rings, with a particularly prominent ring formed at a radius of 32,000 ly (9.8 kpc) from the core,[85] nicknamed by some astronomers the ring of fire.[86] This ring is hidden from visible light images of the galaxy because it is composed primarily of cold dust, and most of the star formation that is taking place in the Andromeda Galaxy is concentrated there.[87]

Later studies with the help of the Spitzer Space Telescope showed how the Andromeda Galaxy’s spiral structure in the infrared appears to be composed of two spiral arms that emerge from a central bar and continue beyond the large ring mentioned above. Those arms, however, are not continuous and have a segmented structure.[83]

Close examination of the inner region of the Andromeda Galaxy with the same telescope also showed a smaller dust ring that is believed to have been caused by the interaction with M32 more than 200 million years ago. Simulations show that the smaller galaxy passed through the disk of the Andromeda Galaxy along the latter’s polar axis. This collision stripped more than half the mass from the smaller M32 and created the ring structures in Andromeda.[88]

It is the co-existence of the long-known large ring-like feature in the gas of Messier 31, together with this newly discovered inner ring-like structure, offset from the barycenter, that suggested a nearly head-on collision with the satellite M32, a milder version of the Cartwheel encounter.[89]

Studies of the extended halo of the Andromeda Galaxy show that it is roughly comparable to that of the Milky Way, with stars in the halo being generally «metal-poor», and increasingly so with greater distance.[51] This evidence indicates that the two galaxies have followed similar evolutionary paths. They are likely to have accreted and assimilated about 100–200 low-mass galaxies during the past 12 billion years.[90] The stars in the extended halos of the Andromeda Galaxy and the Milky Way may extend nearly one-third the distance separating the two galaxies.

Nucleus[edit]

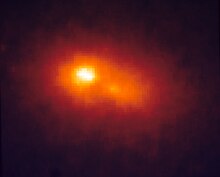

Hubble image of the Andromeda Galaxy core showing possible double structure. NASA/ESA photo.

The Andromeda Galaxy is known to harbor a dense and compact star cluster at its very center. A large telescope creates a visual impression of a star embedded in the more diffuse surrounding bulge. In 1991, the Hubble Space Telescope was used to image the Andromeda Galaxy’s inner nucleus. The nucleus consists of two concentrations separated by 1.5 pc (4.9 ly). The brighter concentration, designated as P1, is offset from the center of the galaxy. The dimmer concentration, P2, falls at the true center of the galaxy and contains a black hole measured at 3–5 × 107 M☉ in 1993,[91] and at 1.1–2.3 × 108 M☉ in 2005.[92] The velocity dispersion of material around it is measured to be ≈ 160 km/s (100 mi/s).[93]

It has been proposed that the observed double nucleus could be explained if P1 is the projection of a disk of stars in an eccentric orbit around the central black hole.[94] The eccentricity is such that stars linger at the orbital apocenter, creating a concentration of stars. It has been postulated that such an eccentric disk could have been formed from the result of a previous black hole merger, where the release of gravitational waves could have «kicked» the stars into to their current eccentric distribution.[95] P2 also contains a compact disk of hot, spectral-class A stars. The A stars are not evident in redder filters, but in blue and ultraviolet light they dominate the nucleus, causing P2 to appear more prominent than P1.[96]

While at the initial time of its discovery it was hypothesized that the brighter portion of the double nucleus is the remnant of a small galaxy «cannibalized» by the Andromeda Galaxy,[97] this is no longer considered a viable explanation, largely because such a nucleus would have an exceedingly short lifetime due to tidal disruption by the central black hole. While this could be partially resolved if P1 had its own black hole to stabilize it, the distribution of stars in P1 does not suggest that there is a black hole at its center.[94]

Discrete sources[edit]

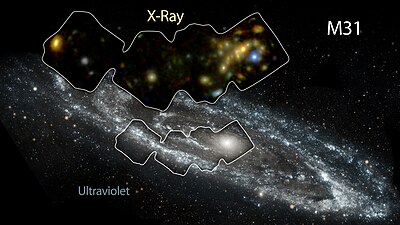

The Andromeda Galaxy in high-energy X-ray and ultraviolet light (released 5 January 2016).

Apparently, by late 1968, no X-rays had been detected from the Andromeda Galaxy.[98] A balloon flight on 20 October 1970, set an upper limit for detectable hard X-rays from the Andromeda Galaxy.[99] The Swift BAT all-sky survey successfully detected hard X-rays coming from a region centered 6 arcseconds away from the galaxy center. The emission above 25 keV was later found to be originating from a single source named 3XMM J004232.1+411314, and identified as a binary system where a compact object (a neutron star or a black hole) accretes matter from a star.[100]

Multiple X-ray sources have since been detected in the Andromeda Galaxy, using observations from the European Space Agency’s (ESA) XMM-Newton orbiting observatory. Robin Barnard et al. hypothesized that these are candidate black holes or neutron stars, which are heating the incoming gas to millions of kelvins and emitting X-rays. Neutron stars and black holes can be distinguished mainly by measuring their masses.[101] An observation campaign of NuSTAR space mission identified 40 objects of this kind in the galaxy.[102]

In 2012, a microquasar, a radio burst emanating from a smaller black hole was detected in the Andromeda Galaxy. The progenitor black hole is located near the galactic center and has about 10 M☉. It was discovered through data collected by the European Space Agency’s XMM-Newton probe and was subsequently observed by NASA’s Swift Gamma-Ray Burst Mission and Chandra X-Ray Observatory, the Very Large Array, and the Very Long Baseline Array. The microquasar was the first observed within the Andromeda Galaxy and the first outside of the Milky Way Galaxy.[103]

Globular clusters[edit]

Star clusters in the Andromeda Galaxy.[104]

There are approximately 460 globular clusters associated with the Andromeda Galaxy.[105] The most massive of these clusters, identified as Mayall II, nicknamed Globular One, has a greater luminosity than any other known globular cluster in the Local Group of galaxies.[106] It contains several million stars and is about twice as luminous as Omega Centauri, the brightest known globular cluster in the Milky Way. Globular One (or G1) has several stellar populations and a structure too massive for an ordinary globular. As a result, some consider G1 to be the remnant core of a dwarf galaxy that was consumed by Andromeda in the distant past.[107] The globular with the greatest apparent brightness is G76 which is located in the southwest arm’s eastern half.[21]

Another massive globular cluster, named 037-B327 and discovered in 2006 as is heavily reddened by the Andromeda Galaxy’s interstellar dust, was thought to be more massive than G1 and the largest cluster of the Local Group;[108] however, other studies have shown it is actually similar in properties to G1.[109]

Unlike the globular clusters of the Milky Way, which show a relatively low age dispersion, Andromeda Galaxy’s globular clusters have a much larger range of ages: from systems as old as the galaxy itself to much younger systems, with ages between a few hundred million years to five billion years.[110]

In 2005, astronomers discovered a completely new type of star cluster in the Andromeda Galaxy. The new-found clusters contain hundreds of thousands of stars, a similar number of stars that can be found in globular clusters. What distinguishes them from the globular clusters is that they are much larger—several hundred light-years across—and hundreds of times less dense. The distances between the stars are, therefore, much greater within the newly discovered extended clusters.[111]

The most massive globular cluster in the Andromeda Galaxy, B023-G078, likely has a central intermediate black hole of almost 100,000 solar masses.[112]

Nearby and satellite galaxies[edit]

Like the Milky Way, the Andromeda Galaxy has satellite galaxies, consisting of over 20 known dwarf galaxies. The Andromeda Galaxy’s dwarf galaxy population is very similar to the Milky Way’s, but the galaxies are much more numerous.[113] The best known and most readily observed satellite galaxies are M32 and M110. Based on current evidence, it appears that M32 underwent a close encounter with the Andromeda Galaxy in the past. M32 may once have been a larger galaxy that had its stellar disk removed by M31 and underwent a sharp increase of star formation in the core region, which lasted until the relatively recent past.[114]

M110 also appears to be interacting with the Andromeda Galaxy, and astronomers have found in the halo of the latter a stream of metal-rich stars that appear to have been stripped from these satellite galaxies.[115] M110 does contain a dusty lane, which may indicate recent or ongoing star formation.[116] M32 has a young stellar population as well.[117]

The Triangulum Galaxy is a non-dwarf galaxy that lies 750,000 light years from Andromeda. It is currently unknown whether it is a satellite of Andromeda.[118]

In 2006, it was discovered that nine of the satellite galaxies lie in a plane that intersects the core of the Andromeda Galaxy; they are not randomly arranged as would be expected from independent interactions. This may indicate a common tidal origin for the satellites.[119]

PA-99-N2 event and possible exoplanet in galaxy[edit]

PA-99-N2 was a microlensing event detected in the Andromeda Galaxy in 1999. One of the explanations for this is the gravitational lensing of a red giant by a star with a mass between 0.02 and 3.6 times that of the Sun, which suggested that the star is likely orbited by a planet. This possible exoplanet would have a mass 6.34 times that of Jupiter. If finally confirmed, it would be the first ever found extragalactic planet. However, anomalies in the event were later found.[120]

Collision with the Milky Way[edit]

Illustration of the collision path between the Milky Way and Andromeda galaxy

The Andromeda Galaxy is approaching the Milky Way at about 110 kilometres (68 miles) per second.[121] It has been measured approaching relative to the Sun at around 300 km/s (190 mi/s)[1] as the Sun orbits around the center of the galaxy at a speed of approximately 225 km/s (140 mi/s). This makes the Andromeda Galaxy one of about 100 observable blueshifted galaxies.[122] Andromeda Galaxy’s tangential or sideways velocity concerning the Milky Way is relatively much smaller than the approaching velocity and therefore it is expected to collide directly with the Milky Way in about 2.5-4 billion years. A likely outcome of the collision is that the galaxies will merge to form a giant elliptical galaxy[123] or possibly large disc galaxy.[16] Such events are frequent among the galaxies in galaxy groups. The fate of Earth and the Solar System in the event of a collision is currently unknown. Before the galaxies merge, there is a small chance that the Solar System could be ejected from the Milky Way or join the Andromeda Galaxy.[124]

Amateur observation[edit]

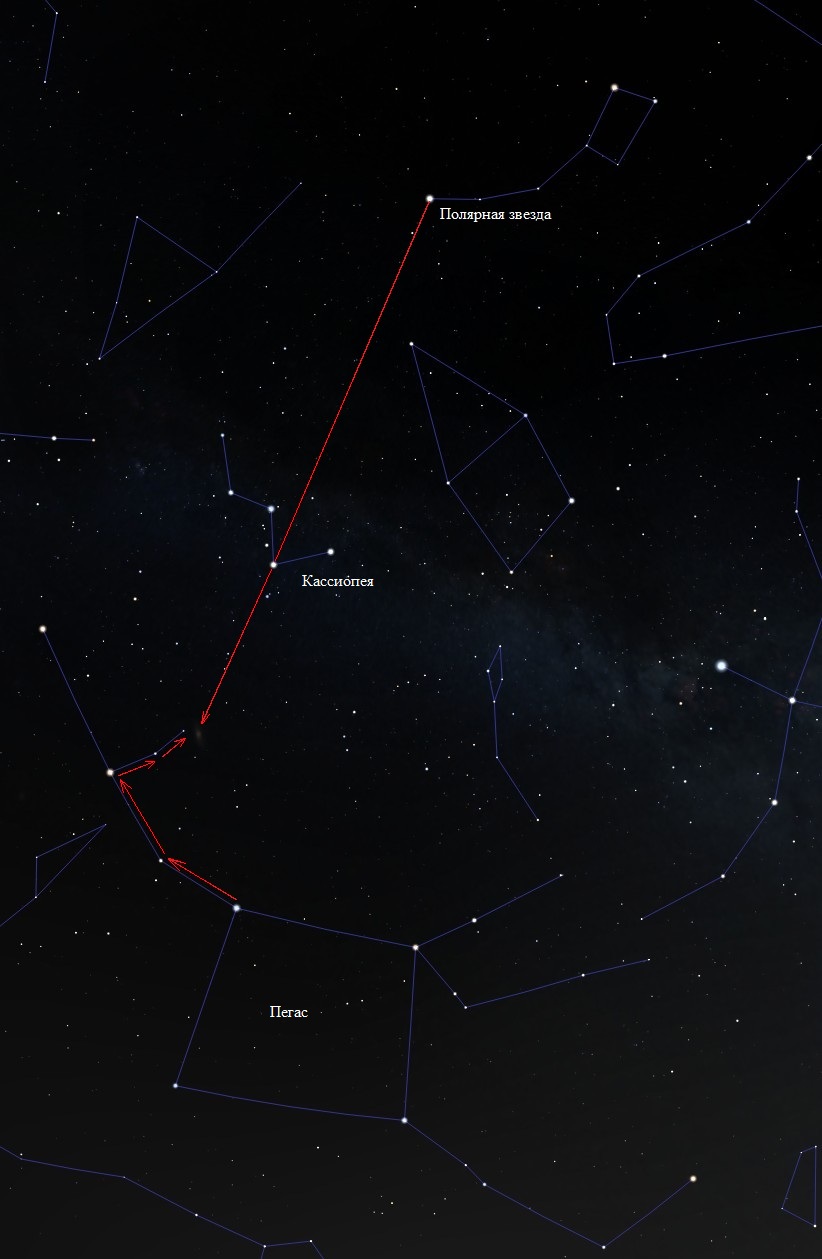

Superimposing picture showing sizes of the Moon and the Andromeda Galaxy as observed from Earth. Because the galaxy is not very bright, its size is not evident.[125][126]

Under most viewing conditions, the Andromeda Galaxy is one of the most distant objects that can be seen with the naked eye (M33 and M81 can be seen under very dark skies).[127][128][129][130] The galaxy is commonly located in the sky about the constellations Cassiopeia and Pegasus. Andromeda is best seen during autumn nights in the Northern Hemisphere when it passes high overhead, reaching its highest point around midnight in October, and two hours earlier each successive month. In the early evening, it rises in the east in September and sets in the west in February.[131] From the Southern Hemisphere the Andromeda Galaxy is visible between October and December, best viewed from as far north as possible. Binoculars can reveal some larger structures of the galaxy and its two brightest satellite galaxies, M32 and M110.[132] An amateur telescope can reveal Andromeda’s disk, some of its brightest globular clusters, dark dust lanes, and the large star cloud NGC 206.[133][134]

See also[edit]

- List of Messier objects

- List of galaxies

- New General Catalogue

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b Blue absolute magnitude of −20.89 – Color index of 0.63 = −21.52

- ^ This is the diameter as measured through the D25 standard. The halo extends up to a distance of 67.45 kiloparsecs (220×103 ly).[9]

- ^ J00443799+4129236 is at celestial coordinates R.A. 00h 44m 37.99s, Dec. +41° 29′ 23.6″.

- ^ average(787 ± 18, 770 ± 40, 772 ± 44, 783 ± 25) = ((787 + 770 + 772 + 783) / 4) ± (182 + 402 + 442 + 252)0.5 / 2 = 778 ± 33.

- ^ Blue absolute magnitude of −21.58 (see reference) – Color index of 0.63 = absolute visual magnitude of −22.21

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j «Results for Messier 31». NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database. NASA/IPAC. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ^ a b c Karachentsev, Igor D.; Kashibadze, Olga G. (2006). «Masses of the Local Group and of the M81 group estimated from distortions in the local velocity field». Astrophysics. 49 (1): 3–18. Bibcode:2006Ap…..49….3K. doi:10.1007/s10511-006-0002-6. S2CID 120973010.

- ^ Riess, Adam G.; Fliri, Jürgen; Valls-Gabaud, David (2012). «Cepheid Period-Luminosity Relations in the Near-Infrared and the Distance to M31 from Thehubble Space Telescopewide Field Camera 3». The Astrophysical Journal. 745 (2): 156. arXiv:1110.3769. Bibcode:2012ApJ…745..156R. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/745/2/156. S2CID 119113794.

- ^ «M 31». Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ^ Gil de Paz, Armando; Boissier, Samuel; Madore, Barry F.; et al. (2007). «The GALEX Ultraviolet Atlas of Nearby Galaxies». Astrophysical Journal. 173 (2): 185–255. arXiv:astro-ph/0606440. Bibcode:2007ApJS..173..185G. doi:10.1086/516636. S2CID 119085482.

- ^ a b c Ribas, Ignasi; Jordi, Carme; Vilardell, Francesc; et al. (2005). «First Determination of the Distance and Fundamental Properties of an Eclipsing Binary in the Andromeda Galaxy». Astrophysical Journal Letters. 635 (1): L37–L40. arXiv:astro-ph/0511045. Bibcode:2005ApJ…635L..37R. doi:10.1086/499161. S2CID 119522151.

- ^ «The median values of the Milky Way and Andromeda masses are MG = 0.8+0.4

−0.3×1012 M☉ and MA = 1.5+0.5

−0.4×1012 M☉ at a 68% level» Peñarrubia, Jorge; Ma, Yin-Zhe; Walker, Matthew G.; McConnachie, Alan W. (29 July 2014). «A dynamical model of the local cosmic expansion». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 433 (3): 2204–2222. arXiv:1405.0306. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.443.2204P. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu879. S2CID 119295582., but compare «[we estimate] the virial mass and radius of the galaxy to be 0.8×1012 ± 0.1×1012 M☉ (1.59×1042 ± 2.0×1041 kg)» Kafle, Prajwal R.; Sharma, Sanjib; Lewis, Geraint F.; et al. (1 February 2018). «The Need for Speed: Escape velocity and dynamical mass measurements of the Andromeda Galaxy». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 475 (3): 4043–4054. arXiv:1801.03949. Bibcode:2018MNRAS.475.4043K. doi:10.1093/mnras/sty082. ISSN 0035-8711. S2CID 54039546. - ^ a b c De Vaucouleurs, Gerard; De Vaucouleurs, Antoinette; Corwin, Herold G.; Buta, Ronald J.; Paturel, Georges; Fouque, Pascal (1991). Third Reference Catalogue of Bright Galaxies. Bibcode:1991rc3..book…..D.

- ^ a b c d e Chapman, Scott C.; Ibata, Rodrigo A.; Lewis, Geraint F.; et al. (2006). «A kinematically selected, metal-poor spheroid in the outskirts of M31». Astrophysical Journal. 653 (1): 255–266. arXiv:astro-ph/0602604. Bibcode:2006ApJ…653..255C. doi:10.1086/508599. S2CID 14774482. Also see the press release, «Andromeda’s Stellar Halo Shows Galaxy’s Origin to Be Similar to That of Milky Way» (Press release). Caltech Media Relations. 27 February 2006. Archived from the original on 9 May 2006. Retrieved 24 May 2006.

- ^ Young, Kelly (6 June 2006). «The Andromeda galaxy hosts a trillion stars». New Scientist. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ Kafle, Prajwal R.; Sharma, Sanjib; Lewis, Geraint F.; et al. (1 February 2018). «The Need for Speed: Escape velocity and dynamical mass measurements of the Andromeda Galaxy». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 475 (3): 4043–4054. arXiv:1801.03949. Bibcode:2018MNRAS.475.4043K. doi:10.1093/mnras/sty082. ISSN 0035-8711. S2CID 54039546.

- ^ «Milky Way tips the scales at 1.5 trillion solar masses» (11 March 2019). AstronomyNow.com. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ^ Mahon, Chris (20 May 2018). «New Research Says the Milky Way Is Far Bigger Than We Thought Possible.» Archived 9 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine OuterPlaces.com. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ^ Schiavi, Riccardo; Capuzzo-Dolcetta, Roberto; Arca-Sedda, Manuel; Spera, Mario (October 2020). «Future merger of the Milky Way with the Andromeda galaxy and the fate of their supermassive black holes». Astronomy & Astrophysics. 642: A30. arXiv:2102.10938. Bibcode:2020A&A…642A..30S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202038674. S2CID 224991193.

- ^ «NASA’s Hubble Shows Milky Way is Destined for Head-On Collision». NASA. 31 May 2012. Archived from the original on 4 June 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- ^ a b Ueda, Junko; Iono, Daisuke; Yun, Min S.; et al. (2014). «Cold molecular gas in merger remnants. I. Formation of molecular gas disks». The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 214 (1): 1. arXiv:1407.6873. Bibcode:2014ApJS..214….1U. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/214/1/1. S2CID 716993.

- ^ Frommert, Hartmut; Kronberg, Christine (22 August 2007). «Messier Object Data, sorted by Apparent Visual Magnitude». SEDS. Archived from the original on 12 July 2007. Retrieved 27 August 2007.

- ^ «M 31, M 32 & M 110». 15 October 2016.

- ^ Hafez, Ihsan (2010). Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi and his book of the fixed stars: a journey of re-discovery (Ph.D. Thesis). James Cook University. Bibcode:2010PhDT…….295H. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ «The Andromeda Galaxy (M31): Location, Characteristics & Images». Space.com. 10 January 2018.

- ^ a b Kepple, George Robert; Sanner, Glen W. (1998). The Night Sky Observer’s Guide. Vol. 1. Willmann-Bell. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-943396-58-3.

- ^ Davidson, Norman (1985). Astronomy and the imagination: a new approach to man’s experience of the stars. Routledge Kegan & Paul. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-7102-0371-7.

- ^ Kant, Immanuel, Universal Natural History and Theory of the Heavens (1755)

- ^ Herschel, William (1785). «On the Construction of the Heavens». Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 75: 213–266. doi:10.1098/rstl.1785.0012. S2CID 186213203.

- ^ Huggins, William (1864). «On the Spectra of Some of the Nebulae». Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 154: 437–444. Bibcode:1864RSPT..154..437H. doi:10.1098/rstl.1864.0013.

- ^ Backhouse, Thomas W. (1888). «Nebula in Andromeda and Nova, 1885». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 48 (3): 108–110. Bibcode:1888MNRAS..48..108B. doi:10.1093/mnras/48.3.108.

- ^ Roberts, I. (1888). «photographs of the nebulæ M 31, h 44, and h 51 Andromedæ, and M 27 Vulpeculæ». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 49 (2): 65–66. Bibcode:1888MNRAS..49…65R. doi:10.1093/mnras/49.2.65.

- ^ LIBRARY, ROYAL ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY/SCIENCE PHOTO. «Andromeda Galaxy, 19th century – Stock Image – C014/5148». Science Photo Library.

- ^ Slipher, Vesto M. (1913). «The Radial Velocity of the Andromeda Nebula». Lowell Observatory Bulletin. 1 (8): 56–57. Bibcode:1913LowOB…2…56S.

- ^ a b Karachentsev, Igor D.; Karachentseva, Valentina E.; Huchtmeier, Walter K.; Makarov, Dmitry I. (2004). «A Catalog of Neighboring Galaxies». Astronomical Journal. 127 (4): 2031–2068. Bibcode:2004AJ….127.2031K. doi:10.1086/382905.

- ^ a b McConnachie, Alan W.; Irwin, Michael J.; Ferguson, Annette M. N.; et al. (2005). «Distances and metallicities for 17 Local Group galaxies». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 356 (4): 979–997. arXiv:astro-ph/0410489. Bibcode:2005MNRAS.356..979M. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2004.08514.x.

- ^ Curtis, Heber Doust (1988). «Novae in Spiral Nebulae and the Island Universe Theory». Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 100: 6. Bibcode:1988PASP..100….6C. doi:10.1086/132128.

- ^ Öpik, Ernst (1922). «An estimate of the distance of the Andromeda Nebula». Astrophysical Journal. 55: 406–410. Bibcode:1922ApJ….55..406O. doi:10.1086/142680.

- ^ Hubble, Edwin P. (1929). «A spiral nebula as a stellar system, Messier 31». Astrophysical Journal. 69: 103–158. Bibcode:1929ApJ….69..103H. doi:10.1086/143167.

- ^ Baade, Walter (1944). «The Resolution of Messier 32, NGC 205, and the Central Region of the Andromeda Nebula». Astrophysical Journal. 100: 137. Bibcode:1944ApJ…100..137B. doi:10.1086/144650.

- ^ Gribbin, John R. (2001). The Birth of Time: How Astronomers Measure the Age of the Universe. Yale University Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-300-08914-1.

- ^ Brown, Robert Hanbury; Hazard, Cyril (1950). «Radio-frequency Radiation from the Great Nebula in Andromeda (M.31)». Nature. 166 (4230): 901–902. Bibcode:1950Natur.166..901B. doi:10.1038/166901a0. S2CID 4170236.

- ^ Brown, Robert Hanbury; Hazard, Cyril (1951). «Radio emission from the Andromeda nebula». MNRAS. 111 (4): 357–367. Bibcode:1951MNRAS.111..357B. doi:10.1093/mnras/111.4.357.

- ^ van der Kruit, Piet C.; Allen, Ronald J. (1976). «The Radio Continuum Morphology of Spiral Galaxies». Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 14 (1): 417–445. Bibcode:1976ARA&A..14..417V. doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.14.090176.002221.

- ^ Ingrosso, Gabriele; Calchi Novati, Sebastiano; De Paolis, Francesco; et al. (2009). «Pixel-lensing as a way to detect extrasolar planets in M31». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 399 (1): 219–228. arXiv:0906.1050. Bibcode:2009MNRAS.399..219I. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.15184.x. S2CID 6606414.

- ^ Beck, Rainer; Berkhuijsen, Elly M.; Giessuebel, Rene; et al. (2020). «Magnetic fields and cosmic rays in M 31». Astronomy & Astrophysics. 633: A5. arXiv:1910.09634. Bibcode:2020A&A…633A…5B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201936481. S2CID 204824172.

- ^ Holland, Stephen (1998). «The Distance to the M31 Globular Cluster System». Astronomical Journal. 115 (5): 1916–1920. arXiv:astro-ph/9802088. Bibcode:1998AJ….115.1916H. doi:10.1086/300348. S2CID 16333316.

- ^ Stanek, Krzysztof Z.; Garnavich, Peter M. (1998). «Distance to M31 With the HST and Hipparcos Red Clump Stars». Astrophysical Journal Letters. 503 (2): 131–141. arXiv:astro-ph/9802121. Bibcode:1998ApJ…503L.131S. doi:10.1086/311539. S2CID 6383832.

- ^ a b Davidge, Timothy (Tim) J.; McConnachie, Alan W.; Fardal, Mark A.; et al. (2012). «The Recent Stellar Archeology of M31 – The Nearest Red Disk Galaxy». The Astrophysical Journal. 751 (1): 74. arXiv:1203.6081. Bibcode:2012ApJ…751…74D. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/751/1/74. S2CID 59933737.

- ^ «Hubble Finds Giant Halo Around the Andromeda Galaxy». Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ Peñarrubia, Jorge; Ma, Yin-Zhe; Walker, Matthew G.; McConnachie, Alan W. (29 July 2014). «A dynamical model of the local cosmic expansion». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 433 (3): 2204–2222. arXiv:1405.0306. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.443.2204P. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu879. S2CID 119295582.

- ^ a b Kafle, Prajwal R.; Sharma, Sanjib; Lewis, Geraint F.; et al. (2018). «The need for speed: escape velocity and dynamical mass measurements of the Andromeda galaxy». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 475 (3): 4043–4054. arXiv:1801.03949. Bibcode:2018MNRAS.475.4043K. doi:10.1093/mnras/sty082. S2CID 54039546.

- ^ Kafle, Prajwal R.; Sharma, Sanjib; Lewis, Geraint F.; Robotham, Aaron S G.; Driver, Simon P. (2018). «The need for speed: Escape velocity and dynamical mass measurements of the Andromeda galaxy». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 475 (3): 4043–4054. arXiv:1801.03949. Bibcode:2018MNRAS.475.4043K. doi:10.1093/mnras/sty082. S2CID 54039546.

- ^ «Milky Way ties with neighbour in galactic arms race». 15 February 2018.

- ^ Science, Samantha Mathewson 2018-02-20T19:05:26Z; Astronomy (20 February 2018). «The Andromeda Galaxy Is Not Bigger Than the Milky Way After All». Space.com.

- ^ a b Kalirai, Jasonjot Singh; Gilbert, Karoline M.; Guhathakurta, Puragra; et al. (2006). «The Metal-Poor Halo of the Andromeda Spiral Galaxy (M31)». Astrophysical Journal. 648 (1): 389–404. arXiv:astro-ph/0605170. Bibcode:2006ApJ…648..389K. doi:10.1086/505697. S2CID 15396448.

- ^ Barmby, Pauline; Ashby, Matthew L. N.; Bianchi, Luciana; et al. (2006). «Dusty Waves on a Starry Sea: The Mid-Infrared View of M31». The Astrophysical Journal. 650 (1): L45–L49. arXiv:astro-ph/0608593. Bibcode:2006ApJ…650L..45B. doi:10.1086/508626. S2CID 16780719.

- ^ Barmby, Pauline; Ashby, Matthew L. N.; Bianchi, Luciana; et al. (2007). «Erratum: Dusty Waves on a Starry Sea: The Mid-Infrared View of M31«. The Astrophysical Journal. 655 (1): L61. Bibcode:2007ApJ…655L..61B. doi:10.1086/511682.

- ^ a b Tamm, Antti; Tempel, Elmo; Tenjes, Peeter; et al. (2012). «Stellar mass map and dark matter distribution in M 31». Astronomy & Astrophysics. 546: A4. arXiv:1208.5712. Bibcode:2012A&A…546A…4T. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201220065. S2CID 54728023.

- ^ Kafle, Prajwal R.; Sharma, Sanjib; Lewis, Geraint F.; Robotham, Aaron S G.; Driver, Simon P. (2018). «The Need for Speed: Escape velocity and dynamical mass measurements of the Andromeda galaxy». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 475 (3): 4043–4054. arXiv:1801.03949. Bibcode:2018MNRAS.475.4043K. doi:10.1093/mnras/sty082. S2CID 54039546.

- ^ Downer, Bethany; Telescope, ESA/Hubble (10 March 2019). «Hubble & Gaia Reveal Weight of the Milky Way: 1.5 Trillion Solar Masses».

- ^ Starr, Michelle (8 March 2019). «The Latest Calculation of Milky Way’s Mass Just Changed What We Know About Our Galaxy». ScienceAlert.com. Archived from the original on 8 March 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ Watkins, Laura L.; et al. (2 February 2019). «Evidence for an Intermediate-Mass Milky Way from Gaia DR2 Halo Globular Cluster Motions». The Astrophysical Journal. 873 (2): 118. arXiv:1804.11348. Bibcode:2019ApJ…873..118W. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ab089f. S2CID 85463973.

- ^ Braun, Robert; Thilker, David A.; Walterbos, René A. M.; Corbelli, Edvige (2009). «A Wide-Field High-Resolution H I Mosaic of Messier 31. I. Opaque Atomic Gas and Star Formation Rate Density». The Astrophysical Journal. 695 (2): 937–953. arXiv:0901.4154. Bibcode:2009ApJ…695..937B. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/695/2/937. S2CID 17996197.

- ^ Draine, Bruce T.; Aniano, Gonzalo; Krause, Oliver; et al. (2014). «Andromeda’s Dust». The Astrophysical Journal. 780 (2): 172. arXiv:1306.2304. Bibcode:2014ApJ…780..172D. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/780/2/172. S2CID 118999676.

- ^ «HubbleSite – NewsCenter – Hubble Finds Giant Halo Around the Andromeda Galaxy (05/07/2015) – The Full Story». hubblesite.org. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ^ Gebhard, Marissa (7 May 2015). «Hubble finds massive halo around the Andromeda Galaxy». University of Notre Dame News.

- ^ Lehner, Nicolas; Howk, Chris; Wakker, Bart (25 April 2014). «Evidence for a Massive, Extended Circumgalactic Medium Around the Andromeda Galaxy». The Astrophysical Journal. 804 (2): 79. arXiv:1404.6540. Bibcode:2015ApJ…804…79L. doi:10.1088/0004-637x/804/2/79. S2CID 31505650.

- ^ «NASA’s Hubble Finds Giant Halo Around the Andromeda Galaxy». 7 May 2015. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ^ a b van den Bergh, Sidney (1999). «The local group of galaxies». Astronomy and Astrophysics Review. 9 (3–4): 273–318. Bibcode:1999A&ARv…9..273V. doi:10.1007/s001590050019. S2CID 119392899.

- ^ Moskvitch, Katia (25 November 2010). «Andromeda ‘born in a collision’«. BBC News. Archived from the original on 26 November 2010. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ Karachentsev, Igor D.; Karachentseva, Valentina E.; Huchtmeier, Walter K.; Makarov, Dmitry I. (2003). «A Catalog of Neighboring Galaxies». The Astronomical Journal. 127 (4): 2031–2068. Bibcode:2004AJ….127.2031K. doi:10.1086/382905.

- ^ McCall, Marshall L. (2014). «A Council of Giants». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 440 (1): 405–426. arXiv:1403.3667. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.440..405M. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu199. S2CID 119087190.

- ^ Tempel, Elmo; Tamm, Antti; Tenjes, Peeter (2010). «Dust-corrected surface photometry of M 31 from Spitzer far-infrared observations». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 509: A91. arXiv:0912.0124. Bibcode:2010A&A…509A..91T. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200912186. S2CID 118705514. wA91.

- ^ Liller, William; Mayer, Ben (1987). «The Rate of Nova Production in the Galaxy». Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 99: 606–609. Bibcode:1987PASP…99..606L. doi:10.1086/132021. S2CID 122526653.

- ^ Mutch, Simon J.; Croton, Darren J.; Poole, Gregory B. (2011). «The Mid-life Crisis of the Milky Way and M31». The Astrophysical Journal. 736 (2): 84. arXiv:1105.2564. Bibcode:2011ApJ…736…84M. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/736/2/84. S2CID 119280671.

- ^ Beaton, Rachael L.; Majewski, Steven R.; Guhathakurta, Puragra; et al. (2006). «Unveiling the Boxy Bulge and Bar of the Andromeda Spiral Galaxy». Astrophysical Journal Letters. 658 (2): L91. arXiv:astro-ph/0605239. Bibcode:2007ApJ…658L..91B. doi:10.1086/514333. S2CID 889325.

- ^ «Dimensions of Galaxies». ned.ipac.caltech.edu.

- ^ «Atlas of the Andromeda Galaxy». ned.ipac.caltech.edu.

- ^ «Astronomers Find Evidence of an Extreme Warp in the Stellar Disk of the Andromeda Galaxy» (Press release). UC Santa Cruz. 9 January 2001. Archived from the original on 19 May 2006. Retrieved 24 May 2006.

- ^ Rubin, Vera C.; Ford, W. Kent Jr. (1970). «Rotation of the Andromeda Nebula from a Spectroscopic Survey of Emission». Astrophysical Journal. 159: 379. Bibcode:1970ApJ…159..379R. doi:10.1086/150317. S2CID 122756867.

- ^ Arp, Halton (1964). «Spiral Structure in M31». Astrophysical Journal. 139: 1045. Bibcode:1964ApJ…139.1045A. doi:10.1086/147844.

- ^ van den Bergh, Sidney (1991). «The Stellar Populations of M31». Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 103: 1053–1068. Bibcode:1991PASP..103.1053V. doi:10.1086/132925. S2CID 249711674.

- ^ Hodge, Paul W. (1966). Galaxies and Cosmology. McGraw Hill.

- ^ Simien, François; Pellet, André; Monnet, Guy; et al. (1978). «The spiral structure of M31 – A morphological approach». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 67 (1): 73–79. Bibcode:1978A&A….67…73S.

- ^ Haas, Martin (2000). «Cold dust in M31 as mapped by ISO». The Interstellar Medium in M31 and M33. Proceedings 232. WE-Heraeus Seminar: 69–72. Bibcode:2000immm.proc…69H.

- ^ Walterbos, René A. M.; Kennicutt, Robert C. Jr. (1988). «An optical study of stars and dust in the Andromeda galaxy». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 198: 61–86. Bibcode:1988A&A…198…61W.

- ^ a b Gordon, Karl D.; Bailin, J.; Engelbracht, Charles W.; et al. (2006). «Spitzer MIPS Infrared Imaging of M31: Further Evidence for a Spiral-Ring Composite Structure». The Astrophysical Journal. 638 (2): L87–L92. arXiv:astro-ph/0601314. Bibcode:2006ApJ…638L..87G. doi:10.1086/501046. S2CID 15495044.

- ^ Braun, Robert (1991). «The distribution and kinematics of neutral gas, HI region in M31». Astrophysical Journal. 372: 54–66. Bibcode:1991ApJ…372…54B. doi:10.1086/169954.

- ^ «ISO unveils the hidden rings of Andromeda» (Press release). European Space Agency. 14 October 1998. Retrieved 24 May 2006.

- ^ Morrison, Heather; Caldwell, Nelson; Harding, Paul; et al. (2008). Young Star Clusters in M 31. Galaxies in the Local Volume, Astrophysics and Space Science Proceedings. Astrophysics and Space Science Proceedings. Vol. 5. pp. 227–230. arXiv:0708.3856. Bibcode:2008ASSP….5..227M. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-6933-8_50. ISBN 978-1-4020-6932-1. S2CID 17519849.

- ^ Pagani, Laurent; Lequeux, James; Cesarsky, Diego; et al. (1999). «Mid-infrared and far-ultraviolet observations of the star-forming ring of M 31». Astronomy & Astrophysics. 351: 447–458. arXiv:astro-ph/9909347. Bibcode:1999A&A…351..447P.

- ^ Aguilar, David A.; Pulliam, Christine (18 October 2006). «Busted! Astronomers Nab Culprit in Galactic Hit-and-Run». Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ Block, David L.; Bournaud, Frédéric; Combes, Françoise; et al. (2006). «An almost head-on collision as the origin of the two off-centre rings in the Andromeda galaxy». Nature. 443 (1): 832–834. arXiv:astro-ph/0610543. Bibcode:2006Natur.443..832B. doi:10.1038/nature05184. PMID 17051212. S2CID 4426420.

- ^ Bullock, James S.; Johnston, Kathryn V. (2005). «Tracing Galaxy Formation with Stellar Halos I: Methods». Astrophysical Journal. 635 (2): 931–949. arXiv:astro-ph/0506467. Bibcode:2005ApJ…635..931B. doi:10.1086/497422. S2CID 14500541.

- ^ Lauer, Tod R.; Faber, Sandra M.; Groth, Edward J.; et al. (1993). «Planetary camera observations of the double nucleus of M31» (PDF). Astronomical Journal. 106 (4): 1436–1447, 1710–1712. Bibcode:1993AJ….106.1436L. doi:10.1086/116737.

- ^ Bender, Ralf; Kormendy, John; Bower, Gary; et al. (2005). «HST STIS Spectroscopy of the Triple Nucleus of M31: Two Nested Disks in Keplerian Rotation around a Supermassive Black Hole». Astrophysical Journal. 631 (1): 280–300. arXiv:astro-ph/0509839. Bibcode:2005ApJ…631..280B. doi:10.1086/432434. S2CID 53415285.

- ^ Gebhardt, Karl; Bender, Ralf; Bower, Gary; et al. (June 2000). «A Relationship between Nuclear Black Hole Mass and Galaxy Velocity Dispersion». The Astrophysical Journal. 539 (1): L13–L16. arXiv:astro-ph/0006289. Bibcode:2000ApJ…539L..13G. doi:10.1086/312840. S2CID 11737403.

- ^ a b Tremaine, Scott (1995). «An Eccentric-Disk Model for the Nucleus of M31». Astronomical Journal. 110: 628–633. arXiv:astro-ph/9502065. Bibcode:1995AJ….110..628T. doi:10.1086/117548. S2CID 8408528.

- ^ Akiba, Tatsuya; Madigan, Ann-Marie (1 November 2021). «On the Formation of an Eccentric Nuclear Disk following the Gravitational Recoil Kick of a Supermassive Black Hole». The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 921 (1): L12. arXiv:2110.10163. Bibcode:2021ApJ…921L..12A. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ac30d9. ISSN 2041-8205. S2CID 239049969.

- ^ «Hubble Space Telescope Finds a Double Nucleus in the Andromeda Galaxy» (Press release). Hubble News Desk. 20 July 1993. Retrieved 26 May 2006.

- ^ Schewe, Phillip F.; Stein, Ben (26 July 1993). «The Andromeda Galaxy has a Double Nucleus». Physics News Update. American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 15 August 2009. Retrieved 10 July 2009.

- ^ Fujimoto, Mitsuaki; Hayakawa, Satio; Kato, Takako (1969). «Correlation between the Densities of X-Ray Sources and Interstellar Gas». Astrophysics and Space Science. 4 (1): 64–83. Bibcode:1969Ap&SS…4…64F. doi:10.1007/BF00651263. S2CID 120251156.

- ^ Peterson, Laurence E. (1973). «Hard Cosmic X-Ray Sources». In Bradt, Hale; Giacconi, Riccardo (eds.). X- and Gamma-Ray Astronomy, Proceedings of IAU Symposium no. 55 held in Madrid, Spain, 11–13 May 1972. X- and Gamma-Ray Astronomy. Vol. 55. International Astronomical Union. pp. 51–73. Bibcode:1973IAUS…55…51P. doi:10.1007/978-94-010-2585-0_5. ISBN 978-90-277-0337-8.

- ^ Marelli, Martino; Tiengo, Andrea; De Luca, Andrea; et al. (2017). «Discovery of periodic dips in the brightest hard X-ray source of M31 with EXTraS». The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 851 (2): L27. arXiv:1711.05540. Bibcode:2017ApJ…851L..27M. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/aa9b2e. S2CID 119266242.

- ^ Barnard, Robin; Kolb, Ulrich C.; Osborne, Julian P. (2005). «Timing the bright X-ray population of the core of M31 with XMM-Newton». arXiv:astro-ph/0508284.

- ^ «Andromeda Galaxy Scanned with High-Energy X-ray Vision». Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 5 January 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- ^ Prostak, Sergio (14 December 2012). «Microquasar in Andromeda Galaxy Amazes Astronomers». Sci-News.com.

- ^ «Star cluster in the Andromeda galaxy». ESA. 4 September 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- ^ Barmby, Pauline; Huchra, John P. (2001). «M31 Globular Clusters in the Hubble Space Telescope Archive. I. Cluster Detection and Completeness». Astronomical Journal. 122 (5): 2458–2468. arXiv:astro-ph/0107401. Bibcode:2001AJ….122.2458B. doi:10.1086/323457. S2CID 117895577.

- ^ «Hubble Spies Globular Cluster in Neighboring Galaxy» (Press release). Hubble news desk STSci-1996-11. 24 April 1996. Archived from the original on 1 July 2006. Retrieved 26 May 2006.

- ^ Meylan, Georges; Sarajedini, Ata; Jablonka, Pascale; et al. (2001). «G1 in M31 – Giant Globular Cluster or Core of a Dwarf Elliptical Galaxy?». Astronomical Journal. 122 (2): 830–841. arXiv:astro-ph/0105013. Bibcode:2001AJ….122..830M. doi:10.1086/321166. S2CID 17778865.

- ^ Ma, Jun; de Grijs, Richard; Yang, Yanbin; et al. (2006). «A ‘super’ star cluster grown old: the most massive star cluster in the Local Group». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 368 (3): 1443–1450. arXiv:astro-ph/0602608. Bibcode:2006MNRAS.368.1443M. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.10231.x. S2CID 15947017.

- ^ Cohen, Judith G. (2006). «The Not So Extraordinary Globular Cluster 037-B327 in M31» (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal. 653 (1): L21–L23. arXiv:astro-ph/0610863. Bibcode:2006ApJ…653L..21C. doi:10.1086/510384. S2CID 1733902.

- ^ Burstein, David; Li, Yong; Freeman, Kenneth C.; et al. (2004). «Globular Cluster and Galaxy Formation: M31, the Milky Way, and Implications for Globular Cluster Systems of Spiral Galaxies». Astrophysical Journal. 614 (1): 158–166. arXiv:astro-ph/0406564. Bibcode:2004ApJ…614..158B. doi:10.1086/423334. S2CID 56003193.

- ^ Huxor, Avon P.; Tanvir, Nial R.; Irwin, Michael J.; et al. (2005). «A new population of extended, luminous, star clusters in the halo of M31». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 360 (3): 993–1006. arXiv:astro-ph/0412223. Bibcode:2005MNRAS.360.1007H. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2005.09086.x. S2CID 6215035.

- ^ Pechetti, Renuka; Seth, Anil; Kamann, Sebastian; Caldwell, Nelson; Strader, Jay (January 2022). «Detection of a 100,000 M ⊙ black hole in M31’s Most Massive Globular Cluster: A Tidally Stripped Nucleus». The Astrophysical Journal. 924 (2): 13. arXiv:2111.08720. Bibcode:2022ApJ…924…48P. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ac339f. S2CID 245876938.

- ^ Higgs, C. R.; McConnachie, A. W. (2021). «Solo dwarfs IV: Comparing and contrasting satellite and isolated dwarf galaxies in the Local Group». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 506 (2): 2766–2779. arXiv:2106.12649. doi:10.1093/mnras/stab1754.

- ^ Bekki, Kenji; Couch, Warrick J.; Drinkwater, Michael J.; et al. (2001). «A New Formation Model for M32: A Threshed Early-type Spiral?». Astrophysical Journal Letters. 557 (1): L39–L42. arXiv:astro-ph/0107117. Bibcode:2001ApJ…557L..39B. doi:10.1086/323075. S2CID 18707442.

- ^ Ibata, Rodrigo A.; Irwin, Michael J.; Lewis, Geraint F.; et al. (2001). «A giant stream of metal-rich stars in the halo of the galaxy M31». Nature. 412 (6842): 49–52. arXiv:astro-ph/0107090. Bibcode:2001Natur.412…49I. doi:10.1038/35083506. PMID 11452300. S2CID 4413139.

- ^ Young, Lisa M. (2000). «Properties of the Molecular Clouds in NGC 205». Astronomical Journal. 120 (5): 2460–2470. arXiv:astro-ph/0007169. Bibcode:2000AJ….120.2460Y. doi:10.1086/316806. S2CID 18728927.

- ^ Rudenko, Pavlo; Worthey, Guy; Mateo, Mario (2009). «Intermediate age clusters in the field containing M31 and M32 stars». The Astronomical Journal. 138 (6): 1985–1989. Bibcode:2009AJ….138.1985R. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/138/6/1985.

- ^ «Messier Object 33». www.messier.seds.org. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ Koch, Andreas; Grebel, Eva K. (March 2006). «The Anisotropic Distribution of M31 Satellite Galaxies: A Polar Great Plane of Early-type Companions». Astronomical Journal. 131 (3): 1405–1415. arXiv:astro-ph/0509258. Bibcode:2006AJ….131.1405K. doi:10.1086/499534. S2CID 3075266.

- ^ An, Jin H.; Evans, N. W.; Kerins, E.; Baillon, P.; Calchi Novati, S.; Carr, B. J.; Creze, M.; Giraud‐Heraud, Y.; Gould, A.; Hewett, P.; Jetzer, Ph.; Kaplan, J.; Paulin‐Henriksson, S.; Smartt, S. J.; Tsapras, Y.; Valls‐Gabaud, D. (2004). «The Anomaly in the Candidate Microlensing Event PA‐99‐N2». The Astrophysical Journal. 601 (2): 845–857. arXiv:astro-ph/0310457. Bibcode:2004ApJ…601..845A. doi:10.1086/380820. ISSN 0004-637X. S2CID 8312033.

- ^ Cowen, Ron (2012). «Andromeda on collision course with the Milky Way». Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2012.10765. S2CID 124815138.

- ^ O’Callaghan, Jonathan (14 May 2018). «Apart from Andromeda, are any other galaxies moving towards us?». Space Facts. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ^ Cox, Thomas J.; Loeb, Abraham (2008). «The collision between the Milky Way and Andromeda». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 386 (1): 461–474. arXiv:0705.1170. Bibcode:2008MNRAS.386..461C. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13048.x. S2CID 14964036.

- ^ Cain, Fraser (2007). «When Our Galaxy Smashes Into Andromeda, What Happens to the Sun?». Universe Today. Archived from the original on 17 May 2007. Retrieved 16 May 2007.

- ^ Plait, Phil (1 January 2014). «Yes, That Picture of the Moon and the Andromeda Galaxy Is About Right». Slate Magazine. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ «Andromeda and the Moon collage». www.noirlab.edu. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ «Can you see other galaxies without a telescope?». starchild.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ King, Bob (9 September 2015). «How to See the Farthest Thing You Can See». Sky & Telescope.

- ^ Garner, Rob (20 February 2019). «Messier 33 (The Triangulum Galaxy)». NASA. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ^ Harrington, Philip S. (2010). Cosmic Challenge: The Ultimate Observing List for Amateurs. Cambridge University Press. pp. 28–29. ISBN 9781139493680.

But can [M81’s] diffuse 7.9-magnitude glow actually be glimpsed without any optical aid? The answer is yes, but with a few important qualifications. Not only must the observing site be extraordinarily dark and completely absent of any atmospheric interferences, either natural or artificial, but the observer must have exceptionally keen vision.

- ^ «M31.html». www.physics.ucla.edu.

- ^ King, Bob (16 September 2015). «Watch Andromeda Blossom in Binoculars». Sky & Telescope.

- ^ «Observing M31, the Andromeda Galaxy». Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ^ «Globular Clusters in the Andromeda Galaxy». www.astronomy-mall.com.

Cite error: A list-defined reference named «nake» is not used in the content (see the help page).

External links[edit]

- The Andromeda Galaxy on WikiSky: DSS2, SDSS, GALEX, IRAS, Hydrogen α, X-Ray, Astrophoto, Sky Map, Articles and images

- StarDate: M31 Fact Sheet

- Messier 31, SEDS Messier pages

- Astronomy Picture of the Day

- A Giant Globular Cluster in M31 1998 October 17.

- M31: The Andromeda Galaxy 2004 July 18.

- Andromeda Island Universe 2005 December 22.

- Andromeda Island Universe 2010 January 9.

- WISE Infrared Andromeda 2010 February 19

- M31 and its central Nuclear Spiral

- Amateur photography – M31

- Globular Clusters in M31 at The Curdridge Observatory

- First direct distance to Andromeda − Astronomy magazine article

- Andromeda Galaxy at SolStation.com

- Andromeda Galaxy at The Encyclopedia of Astrobiology, Astronomy, & Spaceflight

- M31, the Andromeda Galaxy at NightSkyInfo.com

- Than, Ker (23 January 2006). «Strange Setup: Andromeda’s Satellite Galaxies All Lined Up». Space.com.

- Hubble Finds Mysterious Disk of Blue Stars Around Black Hole Hubble observations (20 September 2005) put the mass of the Andromeda core black hole at 140 million solar masses

- M31 (Apparent) Novae Page (IAU)

- Multi-wavelength composite

- Andromeda Project (crowd-source)

- Gray, Meghan; Szymanek, Nik; Merrifield, Michael. «M31 – Andromeda Galaxy». Deep Sky Videos. Brady Haran.

- Andromeda Galaxy (M31) at Constellation Guide

- APOD – 2013 August 1 (M31’s angular size compared with full Moon)

- Hubble’s High-Definition Panoramic View of the Andromeda Galaxy

- Infrared-Radio Image of the Andromeda Galaxy (M31)

- Creative Commons Astrophotography M31 Andromeda image download & processing guide

Что представляет собой ближайшая к нам галактика Туманность Андромеды, и как её найти на звездном небе

Наблюдения галактики Андромеды с древности до наши дней