Терракотовая армия была обнаружена в 1974 году. До сих пор она считается одной из величайших находок современной истории. В результате масштабных раскопок под землей было найдено больше 8 тыс. глиняных воинов и лошадей. Грандиозное произведение искусства стало памятником наследию первого императора Китая — Цинь Шихуанди. Об истории раскопок и их исторической значимости рассказывает SupChina.

Кто помог найти реликвию

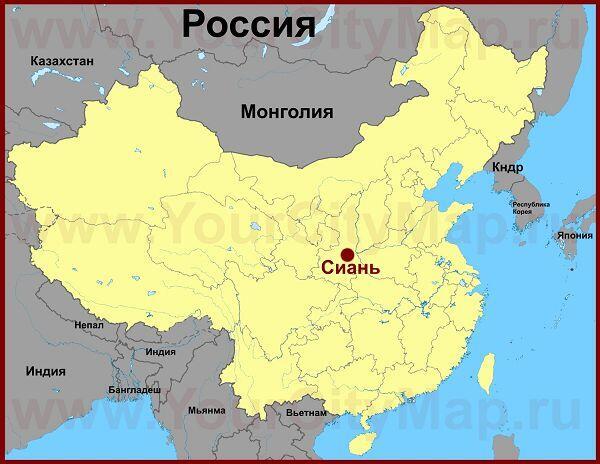

В середине марта 1974 года в пригороде Сианя (провинция Шэньси) семеро фермеров решили выкопать колодец. Шестеро братьев и их сосед, Ван Пучжи, долгое время пытались найти воду, но безуспешно. Наконец Ян Пэйянь, старший из братьев, определил участок в 4,5 м. Там все семеро начали копать.

29 марта фермеры наткнулись на нечто, напоминающее кувшин. Не совсем то, что они искали, но в хозяйстве могло пригодиться. Через какое-то время стало понятно, что это не кувшин, а голова. Из-под земли начала проступать грозная пара глаз, длинные волосы, завязанные в узел, и борода. Кто-то коснулся головы лопатой, и стало очевидно, что сдвинуть ее невозможно.

Братья сделали вывод, что находка абсолютно бесполезна. Более того, откопать нечто подобное — плохая примета, ведь под землей покоятся умершие. За несколько недель количество находок значительно увеличилось: появились очертания новых фигур, наконечники стрел, кирпичи и орудия из бронзы. Некоторые найденные предметы местные забирали себе в качестве сувениров.

Лишь через месяц слухи о находке дошли до директора близлежащего музея Линьтун, Чжао Канминя 赵康民. Чжао сразу догадался, что найденные фигуры связаны с гробницей Цинь Шихуанди, расположенной неподалеку. Многие историки называют Цинь Шихуанди первым императором Китая. Гробница Шихуанди была подробно описана в исторических текстах, однако никаких намеков на «подземную армию» в них не было.

Результаты раскопок

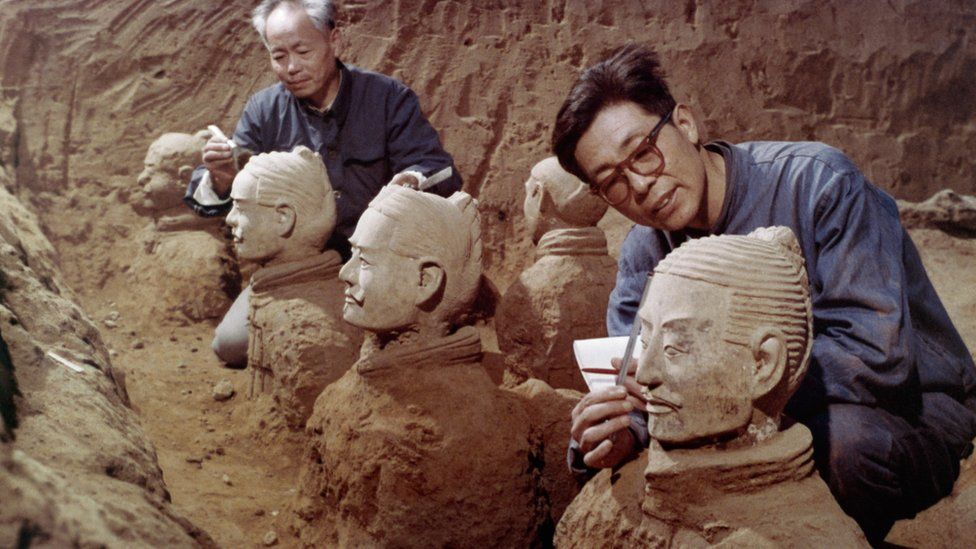

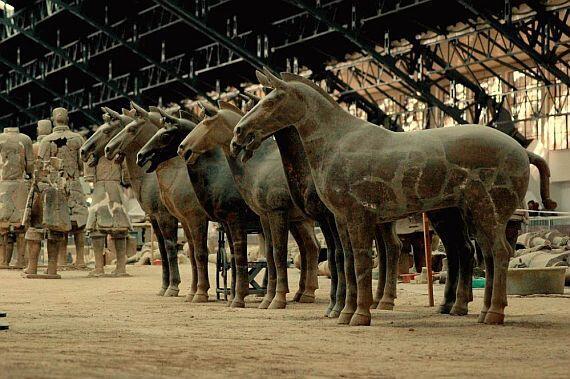

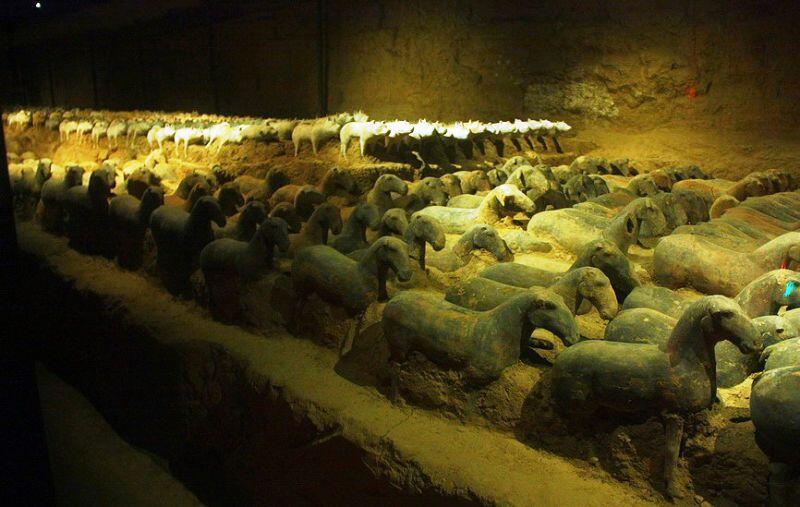

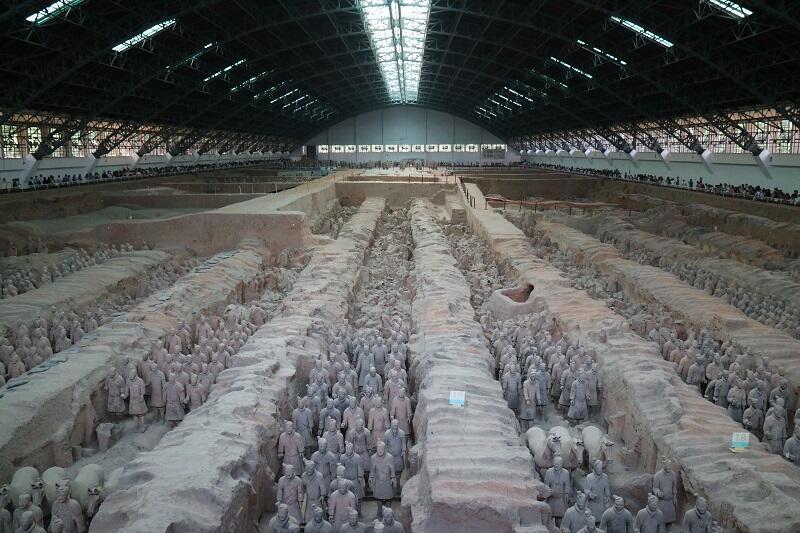

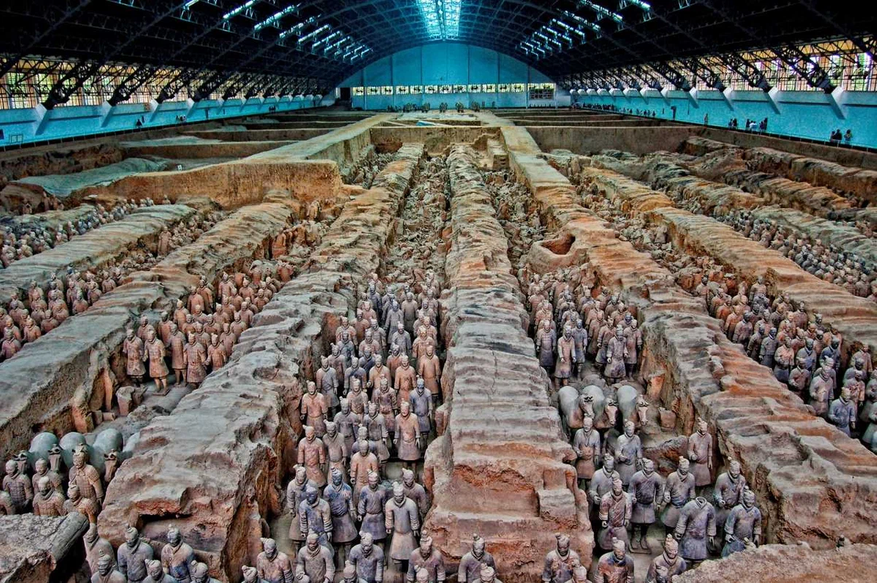

Под руководством Чжао начались масштабные раскопки, в результате которых была обнаружена целая армия воинов. «Терракотовая армия» Цинь Шихуанди ориентировочно включала 8 тыс. керамических воинов, лошадей, боевые колесницы, повозки и другой инвентарь. Было установлено, что фигуры были закопаны в то же время, когда возводилась императорская гробница, то есть за несколько десятилетий до кончины Цинь Шихуанди в 210 году до н. э.

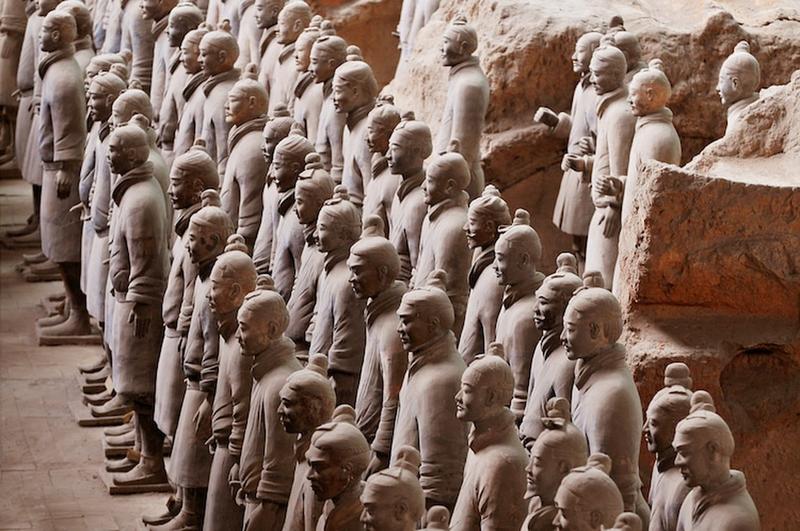

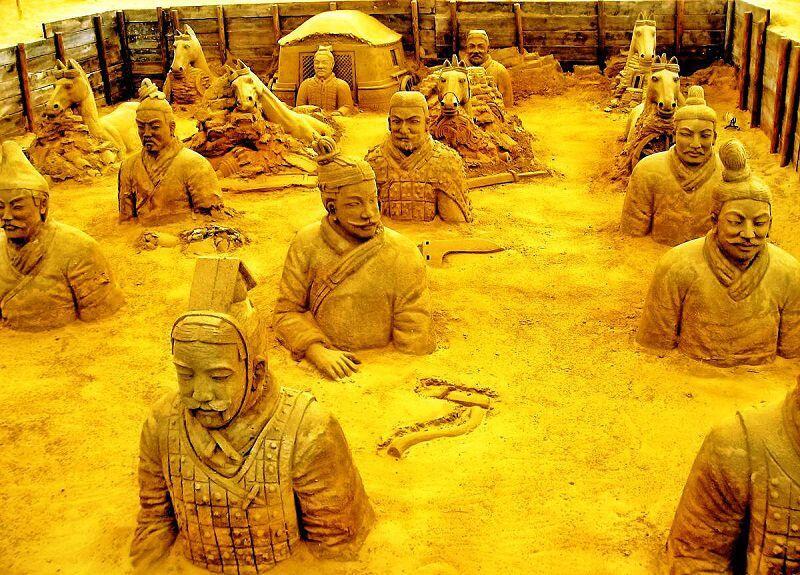

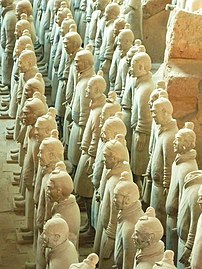

Найденная реликвия стала частью наследия ЮНЕСКО в 1987 году, но ее масштабы до сих пор поражают воображение. В трех углублениях (четвертое было раскопано позже, но оказалось пустым) было найдено больше 6 тыс. солдат. Большая часть войска — пехота, но есть и лучники. Все солдаты были выполнены в натуральную величину и разделены по рангам, средний рост фигур варьируется от 177 до 182 см.

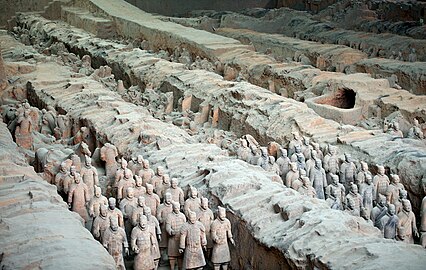

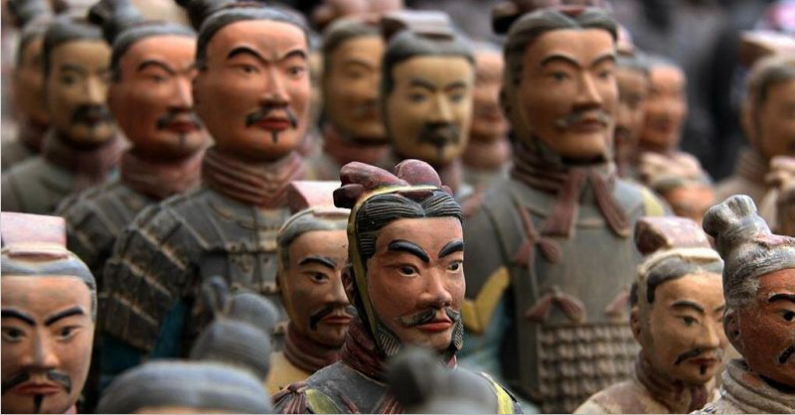

Их тела сделаны по одному образцу, однако каждое лицо уникально. Некоторые считают, что каждый солдат был слеплен по образцу живой копии. Если это так, то сегодня туристы могут видеть лица реальных воинов, живших 2,5 тыс. лет назад. Однако, вероятнее всего, с живых моделей было изготовлено примерно 10 шаблонов, на основе которых создавались все остальные лица.

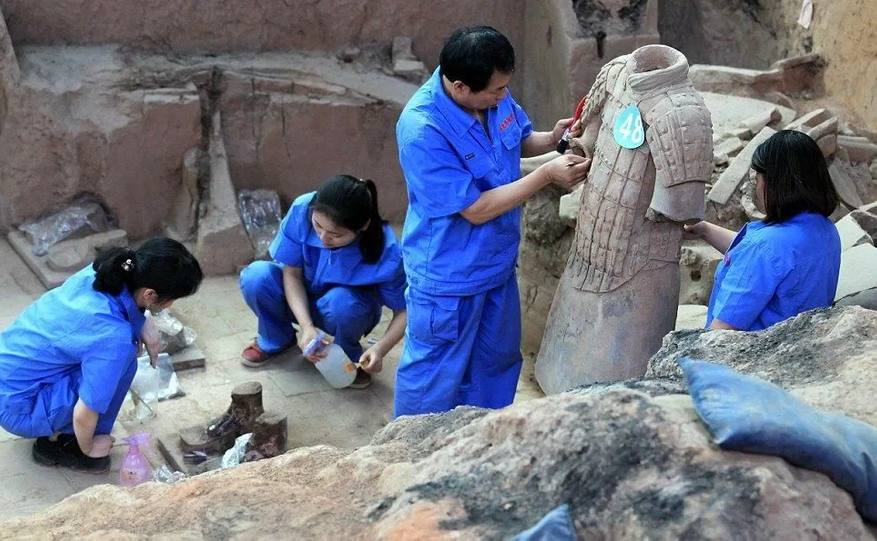

Сейчас фигуры имеют красно-коричневый окрас, однако при погребении они выглядели совсем иначе. Когда «тела» только обнаружили, то на них четко виднелась красная, синяя и фиолетовая краска. На поверхности цвета начали бледнеть из-за кислорода и других факторов. Уже через несколько часов после раскопок фигуры приобрели терракотовый цвет, сохранившийся по сей день.

Чжао Канминь, ушедший из жизни в 2018 году, провозглашал себя «первооткрывателем, реставратором, ценителем и археологом, давшим имя терракотовой армии». Чжао утверждал, что именно он смог их идентифицировать и сложить найденное в общую картину, хотя он не был первооткрывателем фигур.

Чжао защищал реликвию в непростой период культурной революции. Фермеры, обнаружившие терракотовых воинов, пытались добиться признания своих заслуг через суд, но не преуспели.

Терракотовые воины — лишь часть наследия Шихуанди

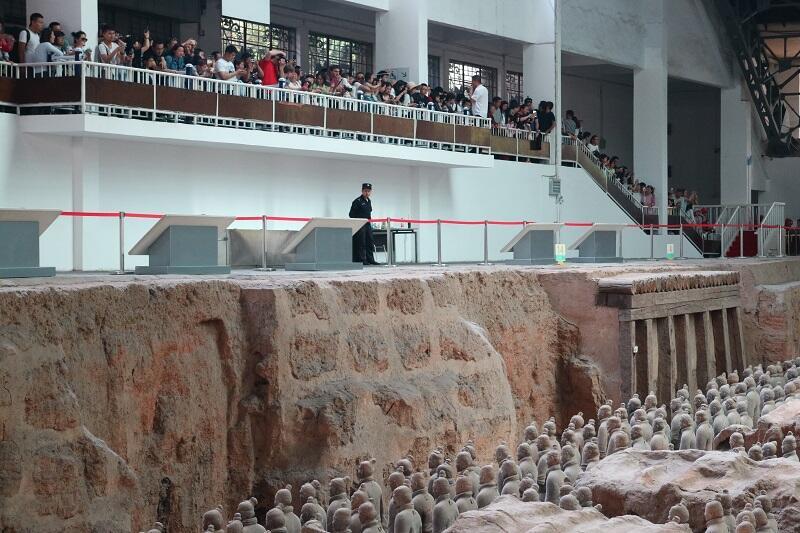

Терракотовая армия во многом стала знаковой реликвией и оказала влияние на имидж страны. Она входит в число самых популярных туристических объектов всего мира, принося немалую прибыль и вызывая общественный интерес.

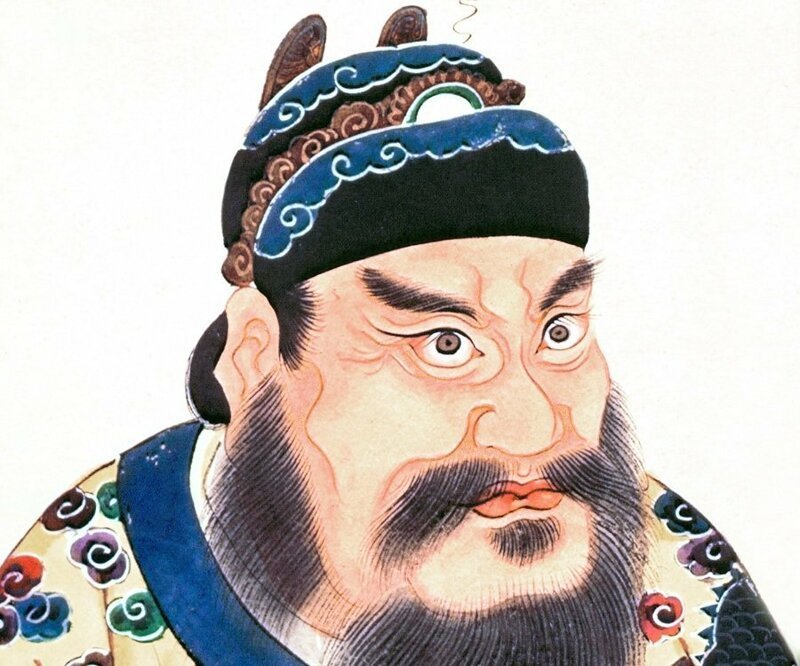

Цинь Шихуанди действительно на какое-то время объединил Китай. Каждый китайский студент знает, что в эпоху Цинь была введена единая валюта, система письменности, система мер и весов и единый тип осей повозок по всей империи. Строились дороги и Великая китайская стена (правда, не в том виде, в котором мы ее знаем сейчас). Правитель Цинь также стал первым обладателем императорского статуса (皇帝).

Несмотря на все достижения Цинь Шихуанди, некоторые утверждают, что его роль в истории переоценена. Формулировка «первый император объединенного Китая» предполагает, что существовало конкретное государство, которое можно было объединить или, наоборот, разделить. Однако это очень спорное утверждение.

Границы государства при Шихуанди даже близко не повторяют его размеров при последующих династиях. Нельзя забывать и о том, что предшествующие династии, или «царства», также имели огромное, сопоставимое с Цинь влияние. Например, государство Чжоу (с 1045 года до н. э. по 221 год до н. э.).

Что скрывает гробница императора

Возможно, самое грандиозное наследие Цинь Шихуанди пока скрыто от потомков. Неподалеку от места, где была обнаружена терракотовая армия, есть небольшой холм, покрывающий мавзолей самого императора. Согласно источникам эпохи Хань, в гробнице императора находится макет его владений. Внутри макета разливаются реки и озера, наполненные ртутью. Подступ к ним охраняется многочисленными ловушками со взрывчаткой.

Вероятнее всего, гробница Шихуанди пока не подвергалась ничьим вторжениям. Согласно последним исследованиям, мавзолей простирается на более чем 90 квадратных километров. Радары показывают, что его содержимое нетронуто. Тем не менее гробница остается запечатанной частично из страха ее повредить. Она таит разгадки не только к жизни императора, но и к борьбе за власть, последовавшей за его уходом.

Спустя долгие годы после раскопок терракотовая армия остается одной из самых впечатляющих достопримечательностей мирового масштаба. Даже скромные выставки с ее отдельными воинами за границей привлекают толпы туристов. Увидев армию вживую, многие начинают интересоваться наследием Цинь Шихуанди, несмотря на его неоднозначность.

Подготовила Анастасия Попова

Подписывайтесь на ЭКД в Телеграме.

Для работы проектов iXBT.com нужны файлы cookie и сервисы аналитики.

Продолжая посещать сайты проектов вы соглашаетесь с нашей

Политикой в отношении файлов cookie

Побольше – это хорошо. Видимо таким принципом и руководствовали создатели терракотового войска, представляющего собой колоссальную скульптурную композицию. Это целая армия, в которой тысячи солдат, да ещё и лошадей подвезли.

Выполнялись статуи в натуральной величине, а для их создания использовалась глина, после чего производился обжиг в печи. Это и послужило толчком для названия – терракотовое войско. Обнаружил сие чудо случайный товарищ, копая колодец.

Создание этих скульптур – настоящий подвиг. Каждая деталь изготавливалась вручную, после чего их собирали в единую статую. Любители конструкторов неистово плюсуют! Уже готовые скульптуры аккуратно клали в печь, где производили обжиг. Финальный штрих – покрытие глазурью и краской.

Детализация – отдельный предмет для разговора. Каждая статуя уникальна, отличается форма тела, экипировка, форма лица.

Средняя высота изделий составляла 200 см, а вот «худышками» скульптуры сложно назвать, ведь они весят 150 кг. Масса лошадей – 300 кг. Самыми интересными являются колесницы, найденные здесь же. Их изготовили из бронзы, а количество деталей перевалило за три сотни.

Каждая колесница имела украшения из серебра и золота, а в упряжке было по 4 лошади. Солдаты располагались лицом на восток. Это важный нюанс, ведь чаще всего недруги нападали именно с данной стороны света.

Воины располагались друг за другом, в 3 ряда. Их поза выдает немирные намерения, готовность ринуться в бой. Создатели постарались на славу, сохранив солдатское построение тех времен.

Скульпторы учли даже национальное многообразие. Среди «солдат» можно встретить китайцев, уйгурийцев, тибетцев, монголов и иных представителей азиатских народов. Одежда и стрижка – полное соответствие с тенденциями тех времен.

Бытует легенда, что скульптуры были сделаны по подобию настоящих людей. Считалось, что после кончины душа переселится в глиняную оболочку, продолжая защищать свою родину.

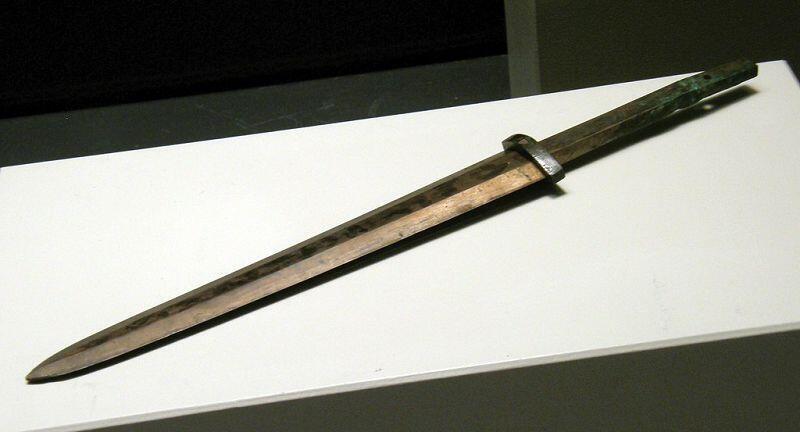

Оружие солдат, изготовленное из бронзы, не рассыпалось за многие века. При исследовании было установлено, что эмаль, нанесенная на фигуры, содержит диоксид хрома. А это уже заявочка на более современные виды оружия. Считается, что хромирование металла впервые было опробовано на Западе только в начале прошлого века. Владели ли кузнецы того времени столь современной технологией?

Ответ сокрыт в сианьской почве. Её уникальный состав, химические и физические свойства позволили сохранить оружие в первозданном виде. Остатки хрома, найденные на мечах и копьях, были обыкновенным загрязнением глазурью, которая наносилась на статуи и деревянные составляющие.

Да, ученые с головой ушли в исследования, провели эксперимент, в ходе которого бронза старела в двух разных камерах с одинаковой скоростью, но отличающейся почвой. И было установлено, что именно сианьская земля сохранила статуи в первозданном виде.

Но это не дает гарантии, что кузнецы и мастера того времени пользовались примитивными методами защиты оружия. Исследования на эту тему продолжаются даже сегодня, но подтвердить или опровергнуть данный факт не представляется возможным.

Честолюбие – сильнейшее качество первого императора династии Цинь, Цинь Шихуанди. Он был совсем юным, когда строители приступили к реализации прекрасной гробницы. Его усыпальница создавалась целых 36 лет, а проект осуществляли почти 700 000 рабочих.

Император Шихуанди – яркая личность. Он был первым, кто внедрил письменность, произвел объединение разрозненных кусков страны, обустроил дороги и каналы. Им же была разработана удобная система измерений и создана первая версия Великой Китайской стены.

Жестокость – ещё одна выдающаяся черта правителя. Никто не должен был узнать о местоположении гробницы. Как только прошли похороны, сам мавзолей, драгоценности, а также рабочих, бывших ещё живыми на тот момент, замуровали. Усыпальницу замаскировали под местность, придав ей вид обыкновенной возвышенности.

Страх смерти присущ многим людям. Император не стал исключением. Он пытался отыскать способ жить вечно, испробовал всевозможные препараты, дойдя до таблеток, содержащих ртуть. Именно они, по одной из версий, привели к смерти.

Сегодня терракотовая армия – это достояние, имеющее невероятную культурную и историческую значимость. Её охраняет ЮНЕСКО, не позволяя независимым экспертам проводить археологические изыскания.

Находка стала настоящим открытием, изменившим представление о Китае того времени. Да, жители Сианя постоянно обнаруживали черепки из глины, но не прикасались к ним. Они расценивали их как проклятый предмет, поэтому всячески избегали. Вполне возможно, что, заинтересуйся ими кто-то всерьез, культурное наследие было бы обнаружено гораздо раньше.

Один из крестьян по имени Янь Джи Ван решил обустроить колодец. Произошло это в 1974 году. На пятиметровой глубине он наткнулся на что-то твердое. И это была голова глиняной статуи. Историки и другие ученые были просто в шоке, когда получили информацию о находке. Они тут же приступили к раскопкам, но к ним допускали далеко не всех специалистов.

Работы осуществляются даже сейчас. Процесс продвигается медленно, с соблюдением всех правил безопасности, так как не хочется повредить скульптуры, простоявшие 22 века. Производитель точно не сможет починить их по гарантии.

Археологам удалось откопать едва половину мавзолея, но есть теория, что на полу усыпальницы присутствует развернутая карта империи. Вполне возможно, что гробница является миниатюрной копией дворца и местности тех времен.

Удивительно, но терракотовая армия умудрилась защитить императора даже в таком виде. Спустя несколько лет с момента гибели правителя в стране произошел переворот. Терракотовые статуи держали в руках настоящее оружие, которое попытались забрать повстанцы, заменив на муляжи. Но далеко не все ушли из усыпальницы живыми. Почему они погибли? Вопрос остается открытым.

29 марта 1974 г. было совершено одно из самых масштабных археологических открытий в XX столетии. Китайский крестьянин Ян Джи Ван решил пробурить на своём участке артезианскую скважину. Дело было к востоку от горы Лишань, примерно в 40 км. от древней столицы Китая, города Сиань.

На глубине около пяти метров он обнаружил глиняную статую воина в полный рост с копьём в руке. Так была найдена знаменитая Терракотовая армия императора Цинь Шихуанди, который в 221 году до н. э. воцарился на всей территории Внутреннего Китая и вошёл в историю как создатель и правитель первого централизованного китайского государства. Датой его смерти принято считать 10 сентября 210 года до н. э. во дворце в Шацю в двух месяцах езды от столицы. Он умер, как сообщается, из-за употребления пилюль бессмертия, содержащих ртуть.

Сначала археологи раскопали 6000 пехотинцев, выстроенных в 11 коридорах подземной галереи. Замершая на века армия предстала во всей красе, одежда ярко раскрашена, на лицах изображена отвага и мужество.

Впрочем, довольно скоро выяснилось, что под первой галереей находится вторая, где расположен глиняный комсостав среднего звена.

Спустя 20 лет уже в совсем другой галерее нашли высшее начальство – генералитет глиняных нойонов, включая главнокомандующего в ламеллярных доспехах, усыпанных драгоценными камнями.

А ещё 7 лет спустя, в 2001 году были найдены первые терракотовые статуи чиновников.

Кроме того, нашли также скульптуры простых крестьян, музыкантов. Следует упомянуть, что внимательно присмотревшись можно отметить абсолютную несхожесть глиняных лиц между собой, учёные предполагают, что их копировали с натуры.

Особняком в загонах стояли скульптуры лошадей, собак, коз, овец, свиней и других животных.

Сейчас общее количество глиняных фигур составляет 8 100 штук. Находка является достоянием КНР. Её принято считать 8 чудом света.

Индивидуальность терракотовых фигур является не единственной особенностью, которую выявила эта находка. Глиняные воины были вооружены более 10 000 экземплярами бронзового оружия. Причём даже спустя 2000 лет оружие находится в рабочем состоянии.

Большое количество оружия позволяет сделать вывод, что для такой массовой продукции не только изготовление керамики, но и металлургия и производство оружия достигали высокой степени индустриализации.

При использовании современных методов анализа установлено, что сохранность оружия обусловлены хромосодержащим покрытием. В то время как современный способ электролитического хромирования был разработан в Германии в 1920-х годах, все ещё остаётся загадкой его применение в древнем Китае.

Исследователи из Пекинского института металлургических технологий попробовали репродуцировать этот процесс. Они нагрели смесь из хромовой руды, уксуса и селитры (KNO3) до 800° C. Полученную жидкость они нанесли на бронзовое оружие. Таким образом можно произвести хромосодержащее покрытие.

Постоянные археологические изыскания, длящиеся уже почти полвека, позволяют предположить, что древний китайский историк Сыма Цянь, описывавший погребение императора, не так уж приукрасил действительность, как полагали до сих пор.

Вот что писал Сыма Цянь:

«В девятой луне прах Шихуана погребли у горы Лишань. Шихуан, впервые придя к власти, тогда же стал устраивать свой склеп. Объединив Поднебесную, он послал туда со всей Поднебесной свыше семисот тысяч преступников. Они углубились до третьих вод, залили стены бронзой и спустили вниз саркофаг. Склеп наполнили перевезенные и опущенные туда копии дворцов, фигуры чиновников всех рангов и воинов всех званий и должностей, редкие вещи и необыкновенные драгоценности. Мастерам приказали сделать луки-самострелы, чтобы, установленные там, они стреляли в тех, кто попытается прорыть ход и пробраться в усыпальницу. Из ртути сделали большие и малые реки и моря, причем ртуть самопроизвольно переливалась в них. На потолке изобразили картину неба, на полу – очертания земли, пересеченной сотней рек, в том числе полноводными Янцзы и Хуанхэ, русла которых вместо воды заполнены ртутью, как и море-океан, обрамляющий империю с востока».

Ещё интересные факты о терракотой армии Китая

Сохранились документы, написанные историографом династии Хань, что собственную гробницу Цинь Шихуанди начал строить сразу после восхождения на трон. В то время ему только исполнилось 13 лет. Масштабная стройка длилась 38 лет. Для создания гигантского мавзолея пришлось задействовать 700 тыс. рабочих.

Исследования материала, из которого сделаны статуи показали, что в глине, даже хорошо обожжённой, обязательно есть участки, где пыльца растений не успела или не смогла перегореть. Анализ этой самой пыльцы показал, что статуи делали в разных концах огромной объединённой империи Цинь Шихуанди, а потом свозили к горе Лишань по дорогам, которые проложили, согласно непреклонной воле Цинь Шихуанди. Это объясняет тот факт, что мастерство и точность передачи лиц фигур разные.

Кроме более 8 тыс. воинов весом в 130 кг каждый, с императором были преданы земле живые люди. Вместе с терракотовой армией своё последнее пристанище нашло 70 тыс. рабочих, задействованных на строительстве гробницы, а также их семьи.

Археологам удалось обнаружить также останки 48 женских тел, которые предположительно являлись наложницами Цинь Шихуанди. Масштабная находка до сих пор хранит множество тайн. Но одно доказано точно: людей закапывали в землю заживо, что подтверждено специальными экспертизами.

Существует несколько предположений того, зачем император отдал приказ захоронить вместе с собой такое количество своих подданных. По одной из версий, жестокий правитель боялся разглашения тайны изготовления глиняных солдат. Потому решил всех людей, причастных к их созданию, забрать с собой. По другой — жрецы-шаманы провели обряд по перемещению их душ в терракотовые фигуры. Это объясняет тот факт, что император предпочёл быть похороненным с глиняными воинами, а не настоящей армией, которые остались живыми. Неподалеку гробницы императора находятся скульптуры музыкантов, государственных служащих и акробатов. Владыка пытался организовать себе такую же комфортную и полноценную жизнь в потустороннем мире, какую имел на этом свете.

Отдельного внимания заслуживают две бронзовые колесницы, запряженные четвёркой глиняных лошадей.

Обе колесницы состоят из 3000 деталей, кропотливо по отдельности отлитых, выкованных, просверленных, заклёпанных, запаянных, отшлифованных и отполированных. Со вставками из золота и серебра и классическими мотивами тигра, дракона и феникса, колесницы считаются наиболее мастерскими произведениями китайской бронзовой технологии, найденными до сего дня.

Императорская повозка. Фото: Commons.wikimedia.org

Почему были прекращены раскопки терракотовой армии

Раскопки возле гробницы императора Цинь Шихуанди ведутся и в наши дни, но только силами китайских археологов. Они действуют не спеша и очень аккуратно, потому что верят в старинную легенду. Она гласит, что в загробном мире возле успокоенных останков правителей могут течь реки из ртути. Специалисты решили тщательно исследовать местность, медленно снимая землю слой за слоем и проверяя на наличие опасных для жизни и здоровья человека веществ.

Каждая новая находка повергает историков в недоумение.

На сегодняшний момент место нахождения терракотовой армии превращено в музей, и попасть в него может каждый, кто оплатил билет. По своей значимости глиняные скульптуры приравниваются к другой достопримечательности страны – Великой Китайской стене.

Интересные факты о терракотой армии Китая. / Фото: ru.sayamatravel.com

Ниже смотрите галерею листая.

«Страшная древняя тайна» с простой разгадкой. История терракотовой армии

4 года назад · 24258 просмотров

Грандиозный погребальный комплекс первого императора, объединившего Китай, является не более чем своего рода справкой для Неба, документом, детально подтверждающим всю жизнь Цинь Шихуанди.

Гробница первого императора династии Цинь.

45 лет назад, 29 марта 1974 г. было совершено одно из самых масштабных археологических открытий в XX столетии. Китайский крестьянин Ян Джи Ван решил пробурить на своём участке артезианскую скважину. Но вместо воды обнаружил глиняную статую воина в полный рост с копьём в руке. Так была найдена знаменитая Терракотовая армия императора Цинь Шихуанди.

Дело было к востоку от горы Лишань, примерно в 40 км. от древней столицы Китая, города Сиань, который выбирали своей резиденцией 13 династий этой древней страны.

Так что поначалу было не вполне ясно, к какому периоду надо отнести этот глиняного мужика, а также его компанию числом 6000 пехотинцев, выстроенных в 11 коридорах подземной галереи. Впрочем, довольно скоро выяснилось, что под первой галереей находится вторая, где расположен глиняный комсостав среднего звена. Спустя 20 лет уже в совсем другой галерее нашли высшее начальство – генералитет глиняных болванов, включая главнокомандующего в чешуйчатых латах, усыпанных драгоценными камнями. А ещё 7 лет спустя пошли имперские тылы – в 2001 г. были найдены первые терракотовые статуи чиновников. Сейчас общее количество глиняных болванов превышает восемь тысяч.

В процессе открытий стало совершенно ясно, что вся эта компания сопровождала в последний путь именно императора Цинь Шихуанди, а не кого-нибудь другого. Впрочем, настоящее имя покойного было всё-таки Ин Чжэн, а Цинь Шихуанди – что-то вроде почётного прозвища, к которым так неравнодушен Китай – вспомним хотя бы «Великого кормчего» Мао Цзэдуна. Цинь Шихуанди и переводится-то довольно похоже: «Великий Вождь Основатель Цинь». Жил он в III веке до нашей эры и сумел вывести страну из двухсотлетнего периода «Воюющих Царств», став первым в истории властителем объединённого Китая.

Отечественному читателю, знакомому со сказками Александра Волкова про приключения в окрестностях Изумрудного города, вся эта китайская археология не могла не напомнить второе произведение знаменитого цикла о Волшебной стране – «Урфин Джюс и его деревянные солдаты». Там одержимый мегаломанией столяр делает серию взводов деревянных воинов-дуболомов, оживляет их при помощи волшебного порошка и отправляется на завоевание мира, поначалу очень даже успешно.

Цинь Шихуанди

Судя по всему, детские впечатления от приключений Элли, Тотошки, Страшилы Мудрого и Железного Дровосека, спасающих мир от боевых деревянных роботов столяра-маньяка, оказались весьма сильными. Настолько, что уже несколько поколений любителей везде и всюду искать «тайное и непознанное», поёт одну и ту же песню, делая из древнего императора какого-то загробного Урфина Джюса. Их хор так силён, что песня приобрела статус респектабельной гипотезы и проникла в сетевые энциклопедии: «По замыслу императора, статуи должны были сопровождать его после смерти, и, вероятно, предоставить ему возможность удовлетворять свои властные амбиции в потустороннем мире так же, как он делал это при жизни».

В принципе, всё это выглядело бы довольно стройно. В это можно было бы если не поверить, то хотя бы принять, как рабочую гипотезу, если бы погребальный комплекс императора ограничивался бы только и исключительно глиняными болванами.

Но фокус в том, что эта восьмитысячная армия – лишь малый, можно сказать, незначительный элемент того грандиозного некрополя, который Цинь Шихуанди начал строить для себя в возрасте 13 лет и продолжал до самой смерти. Постоянные археологические изыскания, длящиеся уже почти полвека, позволяют предположить, что древний китайский историк Сыма Цянь, описывавший погребение императора, не так уж приукрасил действительность, как полагали до сих пор.

Императорская повозка.

Вот что писал Сыма Цянь: «В девятой луне прах Шихуана погребли у горы Лишань. Шихуан, впервые придя к власти, тогда же стал устраивать свой склеп. Объединив Поднебесную, он послал туда со всей Поднебесной свыше семисот тысяч преступников. Они углубились до третьих вод, залили стены бронзой и спустили вниз саркофаг. Склеп наполнили перевезенные и опущенные туда копии дворцов, фигуры чиновников всех рангов и воинов всех званий и должностей, редкие вещи и необыкновенные драгоценности. Мастерам приказали сделать луки-самострелы, чтобы, установленные там, они стреляли в тех, кто попытается прорыть ход и пробраться в усыпальницу. Из ртути сделали большие и малые реки и моря, причем ртуть самопроизвольно переливалась в них. На потолке изобразили картину неба, на полу – очертания земли, пересеченной сотней рек, в том числе полноводными Янцзы и Хуанхэ, русла которых вместо воды заполнены ртутью, как и море-океан, обрамляющий империю с востока».

Повторим – всё это великолепие считали байкой, легендой, не стоящей внимания. До тех самых пор, пока лет тридцать назад не были взяты пробы грунта с участка холма – примерно над предполагаемым Подземным дворцом Шихуанди. Пробы показали, что в центре холма находится относительно компактная зона с аномально высоким содержанием ртути, пары которой дошли до поверхности.

Памятник Цинь Шихуану у кургана с его гробницей

Словом, огромная карта объединённого Китая с ртутными реками и морями, похоже, действительно существует. Вполне возможно, что существует и остальное великолепие, столь красочно описанное Сыма Цянем. А это значит, что вариант «глиняная армия нужна для удовлетворения властных амбиций» рассыпается в прах. Потому что вместе с моделью армии император взял с собой в могилу и модель того Китая, который она завоевала.

Следовательно, снова возникает вопрос – зачем всё это в загробном мире?

На ответ могут навести сравнительно недавние исследования материала, из которого сделаны статуи. В глине, даже хорошо обожжённой, обязательно есть участки, где пыльца растений не успела или не смогла перегореть. Анализ этой самой пыльцы показал, что статуи делали в разных концах огромной объединённой империи Цинь Шихуанди, а потом свозили к горе Лишань по дорогам, которые проложили, согласно непреклонной воле Цинь Шихуанди.

Словом, разгадка довольно проста. И терракотовая армия, и весь грандиозный погребальный комплекс нужны были императору как своего рода доказательство – документ, подтверждающий земное величие «Сына Неба», как называли императоров в Китае. Небо – оно всё видит, и потому главный документ всей жизни должен был по-честному доказывать, что Империя создана, имеет внушительную транспортную связность, а подданные исполняют волю императора как священную. Так сказать, «весомый, зримый, грубый» аргумент перед Небом: «Я, Цинь Шихуанди, прожил жизнь не напрасно и сумел из разрозненных племён создать Великий Китай».

Константин Кудряшов.

Источник:

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Location | Lintong District, Xi’an, Shaanxi, China |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, iii, iv, vi |

| Reference | 441 |

| Inscription | 1987 (11th Session) |

| Website | www.bmy.com.cn |

| Coordinates | 34°23′06″N 109°16′23″E / 34.38500°N 109.27306°E |

|

Location of Terracotta Army in China |

| Terracotta Army | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 兵马俑 | |||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 兵馬俑 | |||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Soldier and horse tomb-figurines | |||||||||||||||

|

The Terracotta Army is a collection of terracotta sculptures depicting the armies of Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of China. It is a form of funerary art buried with the emperor in 210–209 BCE with the purpose of protecting him in his afterlife.

The figures, dating from approximately the late 200s BCE,[1] were discovered in 1974 by local farmers in Lintong County, outside Xi’an, Shaanxi, China. The figures vary in height according to their rank, the tallest being the generals. The figures include warriors, chariots and horses. Estimates from 2007 were that the three pits containing the Terracotta Army hold more than 8,000 soldiers, 130 chariots with 520 horses, and 150 cavalry horses, the majority of which remain in situ in the pits near Qin Shi Huang’s mausoleum.[2] Other, non-military terracotta figures were found in adjoining pits, including officials, acrobats, strongmen, and musicians.[3]

History

The mound where the tomb is located

The construction of the tomb was described by historian Sima Qian (145–90 BCE) in Records of the Grand Historian, the first of China’s 24 dynastic histories, written a century after the mausoleum’s completion. Work on the mausoleum began in 246 BCE, soon after Emperor Qin (then aged 13) succeeded his father as King of Qin, and the project eventually involved 700,000 conscripted workers.[4][5] Geographer Li Daoyuan, writing six centuries after the first emperor’s death, recorded in Shui Jing Zhu that Mount Li was a favoured location due to its auspicious geology: «famed for its jade mines, its northern side was rich in gold, and its southern side rich in beautiful jade; the first emperor, covetous of its fine reputation, therefore chose to be buried there».[6][7] Sima Qian wrote that the first emperor was buried with palaces, towers, officials, valuable artifacts and wondrous objects. According to this account, 100 flowing rivers were simulated using mercury, and above them the ceiling was decorated with heavenly bodies, below which lay the features of the land. Some translations of this passage refer to «models» or «imitations»; however, those words were not used in the original text, which also makes no mention of the terracotta army.[4][8] High levels of mercury were found in the soil of the tomb mound, giving credence to Sima Qian’s account.[9] Later historical accounts suggested that the complex and tomb itself had been looted by Xiang Yu, a contender for the throne after the death of the first emperor.[10][11][12] However, there are indications that the tomb itself may not have been plundered.[13]

Discovery

The Terracotta Army was discovered on 29 March 1974 by a group of farmers—Yang Zhifa, his five brothers, and neighbour Wang Puzhi—who were digging a well approximately 1.5 km (0.93 mi) east of the Qin Emperor’s tomb mound at Mount Li (Lishan),[14][15][16][17] a region riddled with underground springs and watercourses. For centuries, occasional reports mentioned pieces of terracotta figures and fragments of the Qin necropolis – roofing tiles, bricks and chunks of masonry.[18] This discovery prompted Chinese archaeologists, including Zhao Kangmin, to investigate,[19] revealing the largest pottery figurine group ever found. A museum complex has since been constructed over the area, the largest pit being enclosed by a roofed structure.[20]

Necropolis

View of the Terracotta Army

Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor, Hall 1

The Terracotta Army is part of a much larger necropolis. Ground-penetrating radar and core sampling have measured the area to be approximately 98 square kilometers (38 square miles).[21]

The necropolis was constructed as a microcosm of the emperor’s imperial palace or compound,[citation needed] and covers a large area around the tomb mound of the first emperor. The earthen tomb mound is located at the foot of Mount Li and built in a pyramidal shape,[22] and is surrounded by two solidly built rammed earth walls with gateway entrances. The necropolis consists of several offices, halls, stables, other structures as well as an imperial park placed around the tomb mound.[citation needed]

The warriors stand guard to the east of the tomb. Up to 5 m (16 ft) of reddish, sandy soil had accumulated over the site in the two millennia following its construction, but archaeologists found evidence of earlier disturbances at the site. During the excavations near the Mount Li burial mound, archaeologists found several graves dating from the 18th and 19th centuries, where diggers had apparently struck terracotta fragments. These were discarded as worthless and used along with soil to backfill the excavations.[23]

Tomb

The tomb appears to be a hermetically sealed space roughly the size of a football pitch (c. 100 × 75 m).[24][25] The tomb remains unopened, possibly due to concerns over preservation of its artifacts.[24] For example, after the excavation of the Terracotta Army, the painted surface present on some terracotta figures began to flake and fade.[26] The lacquer covering the paint can curl in fifteen seconds once exposed to Xi’an’s dry air and can flake off in just four minutes.[27]

Excavation site

The museum complex containing the excavation sites

Pits

View of Pit 1, the largest excavation pit of the Terracotta Army

Four main pits approximately 7 m (23 ft) deep have been excavated.[28][29] These are located approximately 1.5 km (0.93 mi) east of the burial mound. The soldiers within were laid out as if to protect the tomb from the east, where the Qin Emperor’s conquered states lay.

Pit 1

Pit 1, which is 230 m (750 ft) long and 62 m (203 ft) wide,[30] contains the main army of more than 6,000 figures.[31] Pit 1 has eleven corridors, most more than 3 m (10 ft) wide and paved with small bricks with a wooden ceiling supported by large beams and posts. This design was also used for the tombs of nobles and would have resembled palace hallways when built. The wooden ceilings were covered with reed mats and layers of clay for waterproofing, and then mounded with more soil raising them about 2 to 3 m (6 ft 7 in to 9 ft 10 in) above the surrounding ground level when completed.[32]

Others

Pit 2 has cavalry and infantry units as well as war chariots and is thought to represent a military guard. Pit 3 is the command post, with high-ranking officers and a war chariot. Pit 4 is empty, perhaps left unfinished by its builders.

Some of the figures in Pits 1 and 2 show fire damage, while remains of burnt ceiling rafters have also been found.[33] These, together with the missing weapons, have been taken as evidence of the reported looting by Xiang Yu and the subsequent burning of the site, which is thought to have caused the roof to collapse and crush the army figures below. The terracotta figures currently on display have been restored from the fragments.

Other pits that formed the necropolis have also been excavated.[34] These pits lie within and outside the walls surrounding the tomb mound. They variously contain bronze carriages, terracotta figures of entertainers such as acrobats and strongmen, officials, stone armour suits, burial sites of horses, rare animals and labourers, as well as bronze cranes and ducks set in an underground park.[3]

Warrior figures

Types and appearance

The terracotta figures are life-sized, typically ranging from 175 cm (5.74 ft) to about 200 cm (6.6 ft) (the officers are typically taller). They vary in height, uniform, and hairstyle in accordance with rank. Their faces appear to be different for each individual figure; scholars, however, have identified 10 basic face shapes.[35] The figures are of these general types: armored infantry; unarmored infantry; cavalrymen who wear a pillbox hat; helmeted drivers of chariots with more armor protection; spear-carrying charioteers; kneeling crossbowmen or archers who are armored; standing archers who are not; as well as generals and other lower-ranking officers.[36] There are, however, many variations in the uniforms within the ranks: for example, some may wear shin pads while others not; they may wear either long or short trousers, some of which may be padded; and their body armors vary depending on rank, function, and position in formation.[37] There are also terracotta horses placed among the warrior figures.

Terracotta Army General (Left), Mid-rank officer of the Terracotta Army in Xi’an (right)

Recreated figures of an archer and an officer, showing how they would have looked when painted

Pigments used on the Terracotta warriors

Originally, the figures were painted with ground precious stones, intensely fired bones (white), pigments of iron oxide (dark red), cinnabar (red), malachite (green), azurite (blue), charcoal (black), cinnabar barium copper silicate mix (Chinese purple or Han purple), tree sap from a nearby source, (more than likely from the Chinese lacquer tree) (brown),[38] and other colors including pink, lilac, red, white,[39] and one unidentified color.[38] The colored lacquer finish and individual facial features would have given the figures a realistic feel, with eyebrows and facial hair in black and the faces done in pink.[40]

However, in Xi’an’s dry climate, much of the color coating would flake off in less than four minutes after removing the mud surrounding the army.[38]

Since the time of their discovery, the figures have been noted for their exceptional stylistic realism and individualism, with assessments having found that no two figures share the exact same features.[41][42] The earliest note on this aspect was that of 20th century art historian German Hafner who, in 1986, was the first to speculate on a possible Hellenistic link to these sculptures due to the unusual display of naturalism relative to general Qin era sculpture.[43][44] However, this idea has been disputed by scholars citing «no substantial evidence at all» for contact between ancient Greeks and Chinese builders of the tomb, and contending that the bases of such speculation are often imprecise or false interpretations of source materials or far-fetched conjectures.[45] They argue that such speculations rest on flawed and old «Eurocentric» ideas that assumed other civilizations were incapable of sophisticated artistry and thus foreign artistry must be seen through Western traditions.[46] Recent morphological studies finding a high degree of resemblance between the statues and the region’s modern inhabitants have led some scholars to theorize that the degree of stylistic realism stems from the figures being modelled on actual soldiers.[47] These findings have lent support to a hypothesis that the sculptural naturalism derives from a Qin funerary tradition to realistically duplicate possessions for the underworld, which in the case of the first emperor, extended to his soldiery.[48]

Construction

The terracotta army figures were manufactured in workshops by government laborers and local craftsmen using local materials. Heads, arms, legs, and torsos were created separately and then assembled by luting the pieces together. When completed, the terracotta figures were placed in the pits in precise military formation according to rank and duty.[49]

The faces were created using molds, and at least ten face molds may have been used.[35] Clay was then added after assembly to provide individual facial features to make each figure appear different.[50] It is believed that the warriors’ legs were made in much the same way that terracotta drainage pipes were manufactured at the time. This would classify the process as assembly line production, with specific parts manufactured and assembled after being fired, as opposed to crafting a figure as one solid piece and subsequently firing it. In those times of tight imperial control, each workshop was required to inscribe its name on items produced to ensure quality control. This has aided modern historians in verifying which workshops were commandeered to make tiles and other mundane items for the terracotta army.

Weaponry

A bronze helmet unearthed from the site

An armor unearthed from the site

Most of the figures originally held real weapons, which would have increased their realism. The majority of these weapons were looted shortly after the creation of the army or have rotted away. Despite this, over 40,000 bronze items of weaponry have been recovered, including swords, daggers, spears, lances, battle-axes, scimitars, shields, crossbows, and crossbow triggers. Most of the recovered items are arrowheads, which are usually found in bundles of 100 units.[28][51][52] Studies of these arrowheads suggest that they were produced by self-sufficient, autonomous workshops using a process referred to as cellular production or Toyotism.[53] Some weapons were coated with a 10–15 micrometer layer of chromium dioxide before burial that was believed to have protected them from any form of decay for the last 2200 years.[54][55] However, research in 2019 indicated that the chromium was merely contamination from nearby lacquer, not a means of protecting the weapons. The slightly alkaline pH and small particle size of the burial soil most likely preserved the weapons.[56]

The swords contain an alloy of copper, tin, and other elements including nickel, magnesium, and cobalt.[57] Some carry inscriptions that date their manufacture to between 245 and 228 BCE, indicating that they were used before burial.[58]

Scientific research

In 2007, scientists at Stanford University and the Advanced Light Source facility in Berkeley, California, reported that powder diffraction experiments combined with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy and micro-X-ray fluorescence analysis showed that the process of producing terracotta figures colored with Chinese purple dye consisting of barium copper silicate was derived from the knowledge gained by Taoist alchemists in their attempts to synthesize jade ornaments.[59][60]

Since 2006, an international team of researchers at the UCL Institute of Archaeology have been using analytical chemistry techniques to uncover more details about the production techniques employed in the creation of the Terracotta Army. Using X-ray fluorescence spectrometry of 40,000 bronze arrowheads bundled in groups of 100, the researchers reported that the arrowheads within a single bundle formed a relatively tight cluster that was different from other bundles. In addition, the presence or absence of metal impurities was consistent within bundles. Based on the arrows’ chemical compositions, the researchers concluded that a cellular manufacturing system similar to the one used in a modern Toyota factory, as opposed to a continuous assembly line in the early days of the automobile industry, was employed.[61][62]

Grinding and polishing marks visible under a scanning electron microscope provide evidence for the earliest industrial use of lathes for polishing.[61]

Exhibitions

The first exhibition of the figures outside of China was held at National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) in Melbourne in 1982.[63]

A collection of 120 objects from the mausoleum and 12 terracotta warriors were displayed at the British Museum in London as its special exhibition «The First Emperor: China’s Terracotta Army» from 13 September 2007 to April 2008.[64] This exhibition made 2008 the British Museum’s most successful year and made the British Museum the United Kingdom’s top cultural attraction between 2007 and 2008.[65][66] The exhibition brought the most visitors to the museum since the King Tutankhamun exhibition in 1972.[65] It was reported that the 400,000 advance tickets sold out so fast that the museum extended its opening hours until midnight.[67] According to The Times, many people had to be turned away, despite the extended hours.[68] During the day of events to mark the Chinese New Year, the crush was so intense that the gates to the museum had to be shut.[68] The Terracotta Army has been described as the only other set of historic artifacts (along with the remnants of the wreck of the RMS Titanic) that can draw a crowd by the name alone.[67]

Warriors and other artifacts were exhibited to the public at the Forum de Barcelona in Barcelona between 9 May and 26 September 2004. It was their most successful exhibition ever.[69] The same exhibition was presented at the Fundación Canal de Isabel II in Madrid between October 2004 and January 2005, their most successful ever.[70] From December 2009 to May 2010, the exhibition was shown in the Centro Cultural La Moneda in Santiago de Chile.[71]

The exhibition traveled to North America and visited museums such as the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, Bowers Museum in Santa Ana, California, Houston Museum of Natural Science, High Museum of Art in Atlanta,[72] National Geographic Society Museum in Washington, D.C. and the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto.[73] Subsequently, the exhibition traveled to Sweden and was hosted in the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities between 28 August 2010 and 20 January 2011.[74][75] An exhibition entitled ‘The First Emperor – China’s Entombed Warriors’, presenting 120 artifacts was hosted at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, between 2 December 2010 and 13 March 2011.[76] An exhibition entitled «L’Empereur guerrier de Chine et son armée de terre cuite» («The Warrior-Emperor of China and his terracotta army»), featuring artifacts including statues from the mausoleum, was hosted by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts from 11 February 2011 to 26 June 2011.[77] In Italy, from July 2008 to 16 November 2008, five of the warriors of the terracotta army were displayed in Turin at the Museum of Antiquities,[78] and from 16 April 2010 to 5 September 2010 nine statues were displayed at the Royal Palace in Milan at the exhibition entitled «The Two Empires».[79] The group consisted of a horse, a counselor, an archer and six lancers. The «Treasures of Ancient China» exhibition, showcasing two terracotta soldiers and other artifacts, including the Longmen Grottoes Buddhist statues, was held between 19 February 2011 and 7 November 2011 in four locations in India: National Museum of New Delhi, Prince of Wales Museum in Mumbai, Salar Jung Museum in Hyderabad and National Library of India in Kolkata.[citation needed]

Soldiers and related items were on display from 15 March 2013 to 17 November 2013, at the Historical Museum of Bern.[80]

Several Terracotta Army figures were on display, along with many other objects, in an exhibit entitled «Age of Empires: Chinese Art of the Qin and Han Dynasties» at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City from 3 April 2017, to 16 July 2017.[81][82] An exhibition featuring ten Terracotta Army figures and other artifacts, «Terracotta Warriors of the First Emperor,» was on display at the Pacific Science Center in Seattle, Washington, from 8 April 2017 to 4 September 2017[83][84] before traveling to The Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to be exhibited from 30 September 2017 to 4 March 2018 with the addition of augmented reality.[85][86]

An exhibition entitled «China’s First Emperor and the Terracotta Warriors» was at the World Museum in Liverpool from 9 February 2018 to 28 October 2018.[87] This was the first time in more than 10 years that the warriors travelled to the UK.

An exhibition tour of 120 real-size replicas of Terracotta statues was displayed in the German cities of Frankfurt am Main, Munich, Oberhof, Berlin (at the Palace of the Republic) and Nuremberg between 2003 and 2004.[88][89]

Gallery

See also

- List of World Heritage Sites in China

- Qin bronze chariot

Notes

- ^ Lu Yanchou; Zhang Jingzhao; Xie Jun; Wang Xueli (1988). «TL dating of pottery sherds and baked soil from the Xian Terracotta Army Site, Shaanxi Province, China». International Journal of Radiation Applications and Instrumentation D. 14 (1–2): 283–286. doi:10.1016/1359-0189(88)90077-5.

- ^ Portal 2007, p. 167.

- ^ a b «Decoding the Mausoleum of Emperor Qin Shihuang». China Daily. 13 May 2010. Archived from the original on 18 December 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ a b Sima Qian – Shiji Volume 6 Archived 5 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine 《史記•秦始皇本紀》 Original text: 始皇初即位,穿治酈山,及並天下,天下徒送詣七十餘萬人,穿三泉,下銅而致槨,宮觀百官奇器珍怪徙臧滿之。令匠作機駑矢,有所穿近者輒射之。以水銀為百川江河大海,機相灌輸,上具天文,下具地理。以人魚膏為燭,度不滅者久之。二世曰:»先帝後宮非有子者,出焉不宜。» 皆令從死,死者甚眾。葬既已下,或言工匠為機,臧皆知之,臧重即泄。大事畢,已臧,閉中羨,下外羨門,盡閉工匠臧者,無複出者。樹草木以象山。 Translation: When the First Emperor ascended the throne, the digging and preparation at Mount Li began. After he unified his empire, 700,000 men were sent there from all over his empire. They dug down deep to underground springs, pouring copper to place the outer casing of the coffin. Palaces and viewing towers housing a hundred officials were built and filled with treasures and rare artifacts. Workmen were instructed to make automatic crossbows primed to shoot at intruders. Mercury was used to simulate the hundred rivers, the Yangtze and Yellow River, and the great sea, and set to flow mechanically. Above, the heaven is depicted, below, the geographical features of the land. Candles were made of «mermaid»‘s fat which is calculated to burn and not extinguish for a long time. The Second Emperor said: «It is inappropriate for the wives of the late emperor who have no sons to be free», ordered that they should accompany the dead, and a great many died. After the burial, it was suggested that it would be a serious breach if the craftsmen who constructed the tomb and knew of its treasure were to divulge those secrets. Therefore, after the funeral ceremonies had completed, the inner passages and doorways were blocked, and the exit sealed, immediately trapping the workers and craftsmen inside. None could escape. Trees and vegetation were then planted on the tomb mound such that it resembled a hill.

- ^ «Chinese terra cotta warriors had real, and very carefully made weapons». The Washington Post. 26 November 2012. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ^ Clements 2007, p. 158.

- ^ Shui Jing Zhu Chapter 19 Archived 17 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine 《水經注•渭水》Original text: 秦始皇大興厚葬,營建塚壙於驪戎之山,一名藍田,其陰多金,其陽多美玉,始皇貪其美名,因而葬焉。

- ^ Portal 2007, p. 17.

- ^ Portal 2007, p. 202.

- ^ Shui Jing Zhu Chapter 19 Archived 17 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine 《水經注•渭水》 Original text: 項羽入關,發之,以三十萬人,三十日運物不能窮。關東盜賊,銷槨取銅。牧人尋羊,燒之,火延九十日,不能滅。Translation: Xiang Yu entered the gate, sent forth 300,000 men, but they could not finish carrying away his loot in 30 days. Thieves from northeast melted the coffin and took its copper. A shepherd looking for his lost sheep burned the place, the fire lasted 90 days and could not be extinguished.

- ^ Sima Qian – Shiji Volume 8 Archived 6 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine 《史記•高祖本紀》 Original text: 項羽燒秦宮室,掘始皇帝塚,私收其財物 Translation: Xiang Yu burned the Qin palaces, dug up the First Emperor’s tomb, and expropriated his possessions.

- ^ Han Shu Archived 8 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine《漢書·楚元王傳》:Original text: «項籍焚其宮室營宇,往者咸見發掘,其後牧兒亡羊,羊入其鑿,牧者持火照球羊,失火燒其藏槨。» Translation: Xiang burned the palaces and buildings. Later observers witnessed the excavated site. Afterward, a shepherd lost his sheep which went into the dug tunnel; the shepherd held a torch to look for his sheep, and accidentally set fire to the place and burned the coffin.

- ^ «Royal Chinese treasure discovered». BBC News. 20 October 2005. Archived from the original on 15 December 2006. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Agnew, Neville (3 August 2010). Conservation of Ancient Sites on the Silk Road. Getty Publications. p. 214. ISBN 978-1606060131. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ^ Glancey, Jonathan (12 April 2017). «The Army that Conquered the World». BBC. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ O. Louis Mazzatenta. «Emperor Qin’s Terracotta Army». National Geographic. Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- ^ The precise coordinates are 34°23′5.71″N 109°16′23.19″E / 34.3849194°N 109.2731083°E)

- ^ Clements 2007, pp. 155, 157, 158, 160–161, 166.

- ^ Ingber, Sasha (20 May 2018). «Archaeologist Who Uncovered China’s 8,000-Man Terra Cotta Army Dies At 82». npr.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ «Army of Terracotta Warriors». Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ «Discoveries May Rewrite History of China’s Terra-Cotta Warriors». 12 October 2016. Archived from the original on 19 March 2019. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- ^ 73号 Qin Ling Bei Lu (1 January 1970). «Google maps». Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Clements 2007, p. 160.

- ^ a b «The First Emperor». Channel4.com. Archived from the original on 30 September 2010. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ «Application of geographical methods to explore the underground palace of the Emperor Qin Shi Huang Mausoleum». Retrieved 3 December 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Nature (2003). «Terracotta Army saved from crack up». News@nature. doi:10.1038/news031124-7. Archived from the original on 13 July 2017. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Larmer, Brook (June 2012). «Terra-Cotta Warriors in Color». National Geographic. p. 86. Print.

- ^ a b «The Necropolis of First Emperor of Qin». History.ucsb.edu. Archived from the original on 20 November 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Lothar Ledderose. A Magic Army for the Emperor. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- ^ «Ledderose-A Magic Army For The Emperor | PDF | Ancient History | Army». Scribd. Archived from the original on 11 September 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2023.

- ^ «The Mausoleum of the First Emperor of the Qin Dynasty and Terracotta Warriors and Horses». China.org.cn. 12 September 2003. Archived from the original on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Portal 2007.

- ^ «China unearths 114 new Terracotta Warriors». BBC News. 12 May 2010. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ «Terracotta Accessory Pits». Travelchinaguide.com. 10 October 2009. Archived from the original on 28 September 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ a b The Terra Cotta Warriors. National Geographic Museum. p. 27. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ^ Cotterell, Maurice (June 2004). The Terracotta Warriors: The Secret Codes of the Emperor’s Army. Inner Traditions Bear and Company. pp. 105–112. ISBN 978-1591430339. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ^ Cotterell, Maurice (June 2004). The Terracotta Warriors: The Secret Codes of the Emperor’s Army. Inner Traditions Bear and Company. pp. 103–105. ISBN 978-1591430339. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ^ a b c Larmer, Brook (June 2012). «Terra-Cotta Warriors in Color». National Geographic. pp. 74–87. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ lie, Ma (9 September 2010). «Terracotta army emerges in its true colors». China Daily. Archived from the original on 24 January 2020. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- ^ Imperial Tombs of China. Lithograph Publishing Company. 1995. p. 76.

- ^ von Falkenhausen, Lothar (2008). «Action and Image in Early Chinese Art». Cahiers d’Extrême-Asie. 17: 51–91. doi:10.3406/asie.2008.1272. ISSN 0766-1177. JSTOR 44171471. Archived from the original on 30 January 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ Chen, Yumin (2013). «Reflections on China’s First Collection of Terracotta Acrobats (an exhibition review)». Visual Communication. 12 (4): 497–502. doi:10.1177/1470357213498175. ISSN 1470-3572. S2CID 147420437. Archived from the original on 30 January 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ Qingbo, Duan (2022). «Sino-Western Cultural Exchange as Seen through the Archaeology of the First Emperor’s Necropolis». Journal of Chinese History 中國歷史學刊. 7: 21–72. doi:10.1017/jch.2022.25. ISSN 2059-1632. S2CID 251690411. Archived from the original on 30 January 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ «Early links with West likely inspiration for Terracotta Warriors, argues SOAS scholar». School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London. Archived from the original on 6 October 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- ^ «Chinese archaeologist refutes BBC report on Terracotta Warriors». China Daily 中國日報. Xinhua 新華網. www.chinadaily.com. 18 October 2016. Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ Hanink, Johanna; Silva, Felipe Rojas (20 November 2016). «Why China’s Terracotta Warriors Are Stirring Controversy». Live Science. Archived from the original on 5 January 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2017. Originally published in Hanink, Johanna; Silva, Felipe Rojas (18 November 2016). «Why there’s so much backlash to the theory that Greek art inspired China’s Terracotta Army». The Conversation. Archived from the original on 14 September 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ Hu, Yungang; Wang, Jingyang; Lan, Dexing (1 May 2021). «Statistical analysis of the differences of head and face features between terracotta warriors and modern multi ethnic groups based on 3D information extraction». IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 783 (1): 012096. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/783/1/012096. ISSN 1755-1307. S2CID 235387759. Archived from the original on 30 January 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ Hu, Yungang; Lan, Desheng; Wang, Jingyang; Hou, Miaole; Li, Songnian; Li, Xiuzhen; Zhu, Lei (21 March 2022). «Measurement and analysis of facial features of terracotta warriors based on high-precision 3D point clouds». Heritage Science. 10 (1): 40. doi:10.1186/s40494-022-00662-0. ISSN 2050-7445. S2CID 247572024. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ «A Magic Army for the Emperor». Upf.edu. 1 October 1979. Archived from the original on 28 November 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Portal 2007, p. 170.

- ^ «Exquisite Weaponry of Terra Cotta Army». Travelchinaguide.com. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Marcos Martinón-Torres; Xiuzhen Janice Li; Andrew Bevan; Yin Xia; Zhao Kun; Thilo Rehren (2011). «Making Weapons for the Terracotta Army». Archaeology International. 13: 65–75. doi:10.5334/ai.1316.

- ^ Pinkowski, Jennifer (26 November 2012). «Chinese terra cotta warriors had real, and very carefully made, weapons». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ^ «Terracotta Warriors (Terracotta Army)». China Tour Guide. Archived from the original on 29 October 2019. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ^ Zhewen Luo (1993). China’s imperial tombs and mausoleums. Foreign Languages Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-7-119-01619-1. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Martinón-Torres, Marcos; et al. (4 April 2019). «Surface chromium on Terracotta Army bronze weapons is neither an ancient anti-rust treatment nor the reason for their good preservation». Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 5289. Bibcode:2019NatSR…9.5289M. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-40613-7. PMC 6449376. PMID 30948737.

- ^ «Terracotta Warriors» (PDF). National Geographic. 2009. Retrieved 28 July 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ «The First Emperor – China’s Terracotta Army – Teacher’s Resource Pack» (PDF). British Museum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- ^ Bertrand, Loïc; Robinet, Laurianne; Thoury, Mathieu; Janssens, Koen; Cohen, Serge X.; Schöder, Sebastian (26 November 2011). «Cultural heritage and archaeology materials studied by synchrotron spectroscopy and imaging». Applied Physics A. 106 (2): 377–396. doi:10.1007/s00339-011-6686-4. S2CID 95827070.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Liu, Z.; Mehta, A.; Tamura, N.; Pickard, D.; Rong, B.; Zhou, T.; Pianetta, P. (November 2007). «Influence of Taoism on the invention of the purple pigment used on the Qin terracotta warriors». Journal of Archaeological Science. 34 (11): 1878–1883. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.381.8552. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2007.01.005. S2CID 17797649.

- ^ a b Rees, Simon (6 March 2014). «Chemistry unearths the secrets of the Terracotta Army». Education in Chemistry. Vol. 51, no. 2. Royal Society of Chemistry. pp. 22–25. Archived from the original on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ Martinón-Torres, Marcos; Li, Xiuzhen Janice; Bevan, Andrew; Xia, Yin; Zhao, Kun; Rehren, Thilo (20 October 2012). «Forty Thousand Arms for a Single Emperor: From Chemical Data to the Labor Organization Behind the Bronze Arrows of the Terracotta Army» (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory. 21 (3): 534. doi:10.1007/s10816-012-9158-z. S2CID 163088428. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ Jefferson, Dee (16 December 2018). «China’s terracotta warriors will visit Melbourne for National Gallery of Victoria’s Winter Masterpieces series». Arts. ABC News. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ^ «The First Emperor: China’s Terracotta Army». British Museum. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- ^ a b Higgins, Charlotte (2 July 2008). «Terracotta army makes British Museum favourite attraction». The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ «British Museum sees its most successful year ever». Best Western. 3 July 2008. Archived from the original on 11 October 2008.

- ^ a b «British Museum ponders 24-hour opening for terracotta warriors». CBC News. 22 November 2007. Archived from the original on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ a b Whitworth, Damian (9 July 2008). «Is the British Museum the greatest museum on earth?». The Times. London. Archived from the original on 16 June 2011. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ DesarrolloWeb (19 April 2007). «Los guerreros de Xian, en el Forum de Barcelona». Guiarte.com. Archived from the original on 28 March 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ «Guerreros de Xian». Futuropasado.com. Archived from the original on 19 March 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ «Llegan a Chile los legendarios Guerreros de Terracota de China». Latercera.com. Archived from the original on 21 October 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ «Record-Breaking Terracotta Army Exhibition at Atlanta museum». Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

- ^ «ROM’s terracotta warriors show a blockbuster». CBC. 6 January 2011. Archived from the original on 10 January 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ^ «China’s Terracotta Army, Stockholm, Sweden, Reviews». Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- ^ «World Famous Terracotta Army Arrives in Stockholm for Exhibition at Ostasiatiska Museum». Archived from the original on 22 November 2008. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- ^ «Terracotta warriors, Picassos heading to Sydney». ABC News. 14 October 2010. Archived from the original on 12 November 2012. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- ^ «Empereur Guerrier De Chine Et Son Armee De Terre Cuite». Mbam.qc.ca. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ «Il Celeste Impero. Guerrieri di terracotta a Torino – Il Sole 24 ORE». Archived from the original on 21 January 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ «Esercito di Terracotta: dalla Cina a Palazzo Reale di Milano – NanoPress Viaggi». 9 April 2010. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ «Die Terrakotta-Krieger sind da». Der Bund. 22 February 2013. Archived from the original on 22 June 2015. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- ^ Age of Empires: Chinese Art of the Qin and Han Dynasties Archived 11 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ ‘Age of Empires: Chinese Art of the Qin and Han Dynasties (221 B.C.–A.D. 220)’ Review: Treasures of Nation-Building Archived 12 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine Wall Street Journal

- ^ Upchurch, Michael (7 April 2017). «‘Terracotta Warriors’ exhibit makes grand entrance at Pacific Science Center». Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ^ «Terracotta Warriors of the First Emperor». Pacific Science Center. Archived from the original on 11 July 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ^ «Why the Terracotta Warriors are so special, and how to see them in Philly». Philly.com. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ^ Hurdle, Jon (29 September 2017). «Arming China’s Terracotta Warriors – With Your Phone». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 3 October 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ^ «World Museum, Liverpool museums». www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk. Archived from the original on 21 December 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- ^ «Einmarsch der Chinesen». Der Tagesspiegel (in German). 16 January 2004. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ «Tschüss Berlin! Terrakotta-Krieger des Kaisers von China ziehen weiter». Berliner Morgenpost (in German). Deutsche Presse-Agentur. 25 July 2004. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

Bibliography

- Clements, Jonathan (18 January 2007). The First Emperor of China. Sutton. ISBN 978-0-7509-3960-7.

- Debaine-Francfort, Corinne (1999). The Search for Ancient China. ‘New Horizons’ series. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-30095-4.

- Dillon, Michael (1998). China: A Historical and Cultural Dictionary. Durham East Asia series. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon. ISBN 978-0-7007-0439-2.

- Portal, Jane (2007). The First Emperor: China’s Terracotta Army. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02697-1.

- Ledderose, Lothar (2000). «A Magic Army for the Emperor». Ten Thousand Things: Module and Mass Production in Chinese Art. The A.W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00957-5.

- Perkins, Dorothy (2000). Encyclopedia of China: The Essential Reference to China, Its History and Culture. Facts On File. ISBN 978-0-8160-4374-3.

External links

- UNESCO description of the Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor

- Emperor Qinshihuang’s Mausoleum Site Museum (official website)

- People’s Daily article on the Terracotta Army

- OSGFilms Video Article : Terracotta Warriors at Discovery Times Square

- Tomb of the First Emperor of China by Professor Anthony Barbieri, UCSB

- China’s Terracotta Warriors Documentary produced by the PBS Series Secrets of the Dead