https://ria.ru/20221116/sechenie-1832065968.html

Гармония во всем: что такое золотое сечение и способы его применения

Золотое сечение: что это такое, пропорции, принцип, применение в архитектуре и строительстве

Гармония во всем: что такое золотое сечение и способы его применения

«Божественная гармония» или золотое сечение – правило соотношения частей и целого, универсальное проявление красоты и симметрии. Оно встречается в науке,… РИА Новости, 16.11.2022

2022-11-16T21:08

2022-11-16T21:08

2022-11-16T21:08

общество

европа

греция

ле корбюзье (шарль-эдуар жаннере-гри)

леонардо да винчи

/html/head/meta[@name=’og:title’]/@content

/html/head/meta[@name=’og:description’]/@content

https://cdnn21.img.ria.ru/images/07e6/0b/10/1832031636_0:318:3076:2048_1920x0_80_0_0_74519bda270895480ff99027b7b160ec.jpg

МОСКВА, 16 ноя — РИА Новости. «Божественная гармония» или золотое сечение – правило соотношения частей и целого, универсальное проявление красоты и симметрии. Оно встречается в науке, природе, архитектуре, искусстве. Что такое ряд чисел Фибоначчи, принцип расчета и метод построения на основе пропорций – в материале РИА Новости.Золотое сечение»Определенные пропорции повсеместно используются в дизайне и архитектуре, фотографии и очень часто наблюдаются в естественной природе», – говорит Ренат Мансуров, профессиональный фотограф, фотохудожник, лауреат и участник международных фотоконкурсов.История»Первым про золотое сечение писал еще Евклид в “Началах”, которые в свое время были вторые по популярности после Библии. Людям свойственно искать закономерности везде, даже там где их нет, поэтому число “фи” всегда было темой для религиозных спекуляций. Леонардо да Винчи, например, считал, что золотое сечение является выражением божественной сущности Троицы», – комментирует Максим Господинко, диджитал-художник, дизайнер, основатель Spoils.По словам эксперта, про эту пропорцию писал Ян Чихольд, использовал Малевич, Монферран построил по ней Исаакиевский собор.»Но, как мне кажется, острое желание привязать всё мироздание к одному закону больше говорит о людях прошлого, чем о самом мире. Ум человека плохо переносит множественность, неточность моделей и просто хаос. Из этой особенности и происходит когнитивное “удобство”, когда порядок и закономерность всё-таки находятся», – отмечает Максим Господинко.»Впервые термин «золотое сечение» («goldener Schnitt») употребил в эпоху резкого роста европейской секуляризации в примечании ко второму изданию своей «Чистой элементарной математики» в 1835 году доктор философии Мартин Ом. Термин был известен ранее (из текста следует, что Ом не сам его придумал), и в дальнейшем быстро распространился в европейской литературе», – поясняет Сергей Дементьев, эксперт сервиса meta-luxury недвижимости «Душа объекта».Эксперт отмечает, что до Ома это соотношение благодаря трактату монаха францисканца Луки Пачоли, изданному в соавторстве с Леонардо да Винчи, с 1509 года именовали в Европе «божественной пропорцией» (лат. «Divina Proportione», итал. «Proporzione Divina»).По мнению Сергея Дементьева, «божественная пропорция» («золотое сечение») как известная концепция красоты (еще древнегреческий скульптор Поликлет сформировал альтернативные правила красоты, а в 20-м веке модернист архитектор Ле Корбюзье разработал собственную систему пропорционирования) обязана своему появлению упадку веросознания: Эпоха Возрождения в Европе – именно историческая попытка Ренессанса веросознания в новых его формах через умозрение и затем деятельное воплощение в культуре (художественное творчество, архитектура, строительство, парковый, ландшафтный и интерьерный дизайн и т.д.).Пионеры Возрождения Пачоли и Леонардо да Винчи («Тайная вечеря» и «Мона Лиза» вписаны в геометрические фигуры) обратили свое внимание на античность, где еще в «Началах» Евклид (ок. 300 лет до нашей эры) говорил о делении отрезка в крайнем и среднем отношении («ἄκρος καὶ μέσος λόγος»), полагая, что на числах построено все мироздание, на идеи Витрувия (ок. 80-70 гг. до нашей эры — после 13 г. до нашей эры), изложенные в «Десяти книгах об архитектуре» (лат. «De architectura libri decem») о применении математики к искусству архитектуры.Пропорции золотого сеченияО том, как высчитывать золотые пропорции, рассказал эксперт в сфере фотографии Ренат Мансуров.»Если взять для примера линию и разделить ее на две части так, чтобы длинная соотносилась с короткой в такой же пропорции, как вся линия соотносится с длинной, получится золотая пропорция», – поясняет он. К слову, она равна всегда 1,618, и это так называемое число «фи» обозначается греческой буквой φ — от имени древнегреческого скульптора Фидия.Ренат Мансуров отмечает, что в правильном прямоугольнике соотношение сторон соответствует золотому сечению.»Интересен этот прямоугольник тем, что сколько бы ни отрезали от него квадратов, он всегда будет оставлять после себя кусочек с золотым соотношением сторон и так до бесконечности», – говорит Ренат Мансуров.Золотое сечение в математикеИтальянский астроном и математик Фибоначчи вывел ряд чисел, в котором значение каждого последующего равно сумме двух предыдущих. Эта закономерность известна как ряд Фибоначчи.»Если представить два квадрата, поставленных рядом, потом добавить квадрат с удвоенной стороной, то получится квадрат 2 на 2. Далее добавить по спирали против часовой стрелки сумму двух предыдущих квадратов. Получится квадрат с длинной стороны три квадрата, далее добавить к стороне квадрата предыдущую сторону, получится 5, потом 8 потом 13 и 21, каждое последующее число — это сумма сложения с предыдущим, то есть получается такая последовательность, которую и вывел Фибоначчи: 0,1,1,2,3,5,8,13,21 и т.д.», – поясняет Ренат Мансуров.0, 1,1 (0+1), 2 (1+1), 3 (1+2), 5 (2+3), 8 (3+5), 13 (5+8), 21 (8+13), 34 (13+21), 55 (21+34), 89 (34+55) и до бесконечности. А при делении последующего числа на предыдущее получается коэффициент золотого сечения. По мере возрастания чисел соотношение приближается к 1,618. К примеру, числа 3 и 5, их соотношение равно 1,666, а если взять 13 и 21, то получается уже 1,625. Данную формулу применяют для расчета пропорций золотого сечения в любой отрасли, на практике чаще всего используют округленное значение 0,62.А если в каждом квадрате построить дугу из одного угла к другому, то получится так называемая спираль Фибоначчи.Правило золотого сеченияНа практике золотое сечение представляет собой пропорцию, соотношение сторон прямоугольника, отрезков определенной длины, других геометрических форм или сопряженных размерных характеристик реальных объектов.Метод золотого сечения»Если построить прямоугольник, используя метод, указанный выше, и встроить в этот прямоугольник линии, используя числа золотого сечения, то получится разграничение прямоугольника несколькими линиями. И если говорить о композиции, то размещая объекты на линиях или их пересечениях, можно максимально выделить эти объекты как смысловые центры, и наоборот, чем дальше от этих точек, тем труднее будет улавливать смысловой центр», – поясняет Ренат Мансуров.Если же совместить спираль Фибоначчи и эту сетку, то получится практически инструкция по использованию золотого сечения в фотографии, живописи и дизайне.Где можно увидеть золотое сечениеЕсли разделить обычное куриное яйцо мысленно пополам в самой широкой его части, то получатся правильные золотые пропорции. Пропорции здания Парфенона в Греции, спирали раковин, пропорции тела человека, спиральные галактики и растения, и еще много всего вокруг.ПриродаПо словам Рената Мансурова, примеров этих золотых чисел и спиралей найти в природе можно множество. «Распределение семян подсолнуха, спиральные раковины, спиральные галактики, соотношения пропорций человеческого тела, и например, если внимательно посмотреть на нераскрытую еловую шишку или ананас с торца, то можно увидеть эти спирали», – отмечает эксперт.Свою точку зрения озвучил Максим Господинко.»У растения есть важная задача — наиболее оптимально расположить свои листья или лепестки, для того чтобы уловить больше солнечного света или просто уместить больше семян. В некоторых случаях есть возможность делать это только по плотной спирали (ананас, еловая шишка, подсолнечник). Кажется, что перед таким растением стоит сложная математическая задача — на какой угол сдвинуть следующую семечку или лепесток, но на самом деле вопрос лишь в том, насколько сильное создается отталкивание от уже существующего элемента.И так складывается, что угол отклонения от предыдущего листка действительно очень близок к отношению «фи», – комментирует эксперт. – Ни одно рациональное отношение не подходит, потому что при повороте под такими углами возникают колонны-лучи с большими дырами, а как мы знаем, семена подсолнечника уложены красивыми спиралями, число которых как раз соответствует числам из ряда Фибоначчи и дыр там никаких нет».По словам Максима Господинко, ряд Фибоначчи можно легко образовать, взяв ноль и единицу, а каждое последующее за ними получить из суммы двух предыдущих. «Моделировать растение конечно не умеет, насколько мне известно, и не знает количества рядов спиралей, а усилие отталкивания следующего элемента регулируется поколениями и естественным отбором, но в итоге приходит именно к “фи”», – отмечает специалист.ЧеловекПропорции золотого сечения прослеживаются и на примере тела человека. К золотой формуле приравнивается абсолютно все: кости, ладони и пальцы, пропорции участков на лице, расстояние вытянутых рук по отношению к телу. Пропорции таковы:ИскусствоМножество произведений искусства и архитектурных шедевров сделаны по принципам золотого сечения. Египетские и пирамиды Майя, греческий Парфенон и так далее. Картины известных художников тоже выполнены с учетом правил золотого сечения.Прослеживаются такие пропорции и в музыкальных произведениях Шуберта, Моцарта, Баха, Шопена и прочих.»Для дизайнера и художника вопрос о золотом сечении стоит лишь в разрезе более широкой темы — пропорционирования. Не каждый использует этот инструмент, хоть и должен, но часто амбициозный художник, схватившись за “божественную истину”, начинает транслировать лишь её, упуская суть художественного высказывания, передачу образа. Пропорция – лишь инструмент и, очевидно, инструмент не должен идти вперёд задачи. Если образ не понят художником, его невозможно передать», – говорит Максим Господинко. Но тем не менее, переоценить важность этой пропорции сложно. Часто чувствительный художник сам интуитивно может расположить элементы в соответствии с “фи”, также оно является достаточно простым инструментом, чтобы создать изящную композицию даже в самых простых вещах.Примеры использования в живописи.Примеры использования золотого сечения в дизайне логотипов.Применение золотого сеченияПримеры пропорции золотого сечения можно видеть при строительстве многих архитектурных сооружений и создании проекта дома, в современном дизайне интерьера при планировании и зонировании пространства, расстановки мебели и даже цветовом оформлении, а также в ландшафтном дизайне при выкладке закрученных дорожек, расположении растений на клумбах и других элементов.Так, к примеру, при строительстве квартир и домов отношение самой большой комнаты к площади всей квартиры равно как 0,62 к 1, меньшее помещение делают с таким же соотношением к площади большей комнаты. Так, кухня – к меньшей комнате, прихожая к кухне, санузел к прихожей, а балкон – к санузлу.Кроме того, с помощью золотого сечения подбирают и цветовое оформление. В интерьере применяют соотношение 10-30-60, основанное на золотом сечении. В пространстве используют три основных цвета: первый – доминирующий, охватывает 60% комнаты (стены и пол). Второй оттенок составляет 30% – мебель. И третий, 10%, приходится на декор.»Существует множество вариантов золотого сечения. Но все они, так или иначе, основаны на числах Фибоначчи. Какие то из них популярны, какие то не очень, но о чем мы говорим сегодня, это то, что выработалось за последние столетия — это явно золотой стандарт, – говорит Ренат Мансуров. – Конечно, нужно понимать, что творчество остается творчеством и отходить от стандарта не возбраняется, но и совсем идти наперекор этим пропорциям не стоит».По мнению эксперта, теория золотого сечения и «божественных пропорций» довольно популярна, но наука не стоит на месте, и сейчас активно исследуются теории восприятия с научной точки зрения. «То, что работает на практике не одно столетие, однозначно должно напоминать каждый раз о том, что эти пропорции проверены временем и сотнями тысяч творческих людей: фотографы, художники, дизайнеры и архитекторы каждый день работают и используют золотые пропорции в своей работе.Высчитывать миллиметры и микроны в надежде сделать ваше творчество золотым, наверное, не стоит, но и забывать о приятных для глаза пропорциях наверняка не нужно», – говорит Ренат Мансуров.Как это делать правильно, каждый решает самостоятельно, существует множество приемов композиции и работы с психологией восприятия, которые вместе могут улучшить работу в разы. «Учитесь правильно и не останавливайтесь в изучении художественных и композиционных приемов, и ваше творчество будет сиять оригинальностью и легкостью восприятия», – советует Ренат Мансуров.Второе золотое сечениеВторое золотое сечение вытекает из основного сечения и дает отношение 44: 56.Максим Господинко отмечает, что золотое сечение – не единственная пропорция, приятная глазу человека, есть “серебряное сечение”. Две величины находятся в «серебряном сечении», если отношение суммы меньшей и удвоенной большей величины к большей то же самое, что и отношение большей величины к меньшей. Также можно отметить, что порядок разлинованной в клетку тетради приятнее полного хаоса чистого листа (если не брать пропорцию самого его формата за порядок).По словам эксперта, пропорция тетрадки в клетку ничем не хуже золотого сечения, но действие на человека она оказывает иное, как будто организуя простейший порядок — один к одному. «Если бы мы использовали такой поворот угла в подсолнухе, то получили бы одну линию семян, в случае с 1/4 — крест. Каждой задаче — свое решение. В случае с растениями им нужно как раз самое иррациональное число. Примечательно, что именно такое число и прослыло божественным», – говорит Максим Господинко.Мифы о золотом сечении»Можно спекулировать на тему того, что где-то в глубине восприятия человека лежит именно закономерность ряда Фибоначчи, вероятно, где-то мы так же решали геометрическую задачу поворота на нужный угол по спирали, может быть, всё живое, так или иначе помнит этот опыт. Но чтобы не очаровываться золотым сечением чрезмерно, можно обратить внимание на любовь человека к зигзагам и орнаментам. Далеко не обязательно строить бабушкин ковёр по “фи”, чтобы на него было приятнее смотреть, чем на голую стену, – считает Максим Господинко. – Оказывается, этот вид визуального комфорта обусловлен строением визуального кортекса человеческого мозга, и такие орнаменты, как мы можем увидеть в традиционных культурах, ложатся в него как недостающий кусочек удобного паззла вместо хаотичного визуального потока внешней среды. Резной наличник лучше голых ставень. Кружева лучше минимализма. Природа лучше асфальта. Потому что экономят ресурсы человека, показывая привычные и близкие формы».

https://ria.ru/20210121/litso-1593906541.html

https://radiosputnik.ria.ru/20220201/piramida-1769426771.html

https://ria.ru/20181111/1532496249.html

европа

греция

РИА Новости

internet-group@rian.ru

7 495 645-6601

ФГУП МИА «Россия сегодня»

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

2022

Новости

ru-RU

https://ria.ru/docs/about/copyright.html

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/

РИА Новости

internet-group@rian.ru

7 495 645-6601

ФГУП МИА «Россия сегодня»

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

https://cdnn21.img.ria.ru/images/07e6/0b/10/1832031636_345:0:3076:2048_1920x0_80_0_0_d15c886e20acd2d1355969b43de06ca8.jpg

РИА Новости

internet-group@rian.ru

7 495 645-6601

ФГУП МИА «Россия сегодня»

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

общество, европа, греция, ле корбюзье (шарль-эдуар жаннере-гри), леонардо да винчи

Общество, Европа, Греция, Ле Корбюзье (Шарль-Эдуар Жаннере-Гри), Леонардо да Винчи

- Золотое сечение

- История

- Пропорции золотого сечения

- Золотое сечение в математике

- Правило золотого сечения

- Метод золотого сечения

- Где можно увидеть золотое сечение

- Природа

- Человек

- Искусство

- Применение золотого сечения

- Второе золотое сечение

- Мифы о золотом сечении

МОСКВА, 16 ноя — РИА Новости. «Божественная гармония» или золотое сечение – правило соотношения частей и целого, универсальное проявление красоты и симметрии. Оно встречается в науке, природе, архитектуре, искусстве. Что такое ряд чисел Фибоначчи, принцип расчета и метод построения на основе пропорций – в материале РИА Новости.

Золотое сечение

«Определенные пропорции повсеместно используются в дизайне и архитектуре, фотографии и очень часто наблюдаются в естественной природе», – говорит Ренат Мансуров, профессиональный фотограф, фотохудожник, лауреат и участник международных фотоконкурсов.

История

«

«Первым про золотое сечение писал еще Евклид в “Началах”, которые в свое время были вторые по популярности после Библии. Людям свойственно искать закономерности везде, даже там где их нет, поэтому число “фи” всегда было темой для религиозных спекуляций. Леонардо да Винчи, например, считал, что золотое сечение является выражением божественной сущности Троицы», – комментирует Максим Господинко, диджитал-художник, дизайнер, основатель Spoils.

По словам эксперта, про эту пропорцию писал Ян Чихольд, использовал Малевич, Монферран построил по ней Исаакиевский собор.

«Но, как мне кажется, острое желание привязать всё мироздание к одному закону больше говорит о людях прошлого, чем о самом мире. Ум человека плохо переносит множественность, неточность моделей и просто хаос. Из этой особенности и происходит когнитивное “удобство”, когда порядок и закономерность всё-таки находятся», – отмечает Максим Господинко.

«

«Впервые термин «золотое сечение» («goldener Schnitt») употребил в эпоху резкого роста европейской секуляризации в примечании ко второму изданию своей «Чистой элементарной математики» в 1835 году доктор философии Мартин Ом. Термин был известен ранее (из текста следует, что Ом не сам его придумал), и в дальнейшем быстро распространился в европейской литературе», – поясняет Сергей Дементьев, эксперт сервиса meta-luxury недвижимости «Душа объекта».

Эксперт отмечает, что до Ома это соотношение благодаря трактату монаха францисканца Луки Пачоли, изданному в соавторстве с Леонардо да Винчи, с 1509 года именовали в Европе «божественной пропорцией» (лат. «Divina Proportione», итал. «Proporzione Divina»).

По мнению Сергея Дементьева, «божественная пропорция» («золотое сечение») как известная концепция красоты (еще древнегреческий скульптор Поликлет сформировал альтернативные правила красоты, а в 20-м веке модернист архитектор Ле Корбюзье разработал собственную систему пропорционирования) обязана своему появлению упадку веросознания: Эпоха Возрождения в Европе – именно историческая попытка Ренессанса веросознания в новых его формах через умозрение и затем деятельное воплощение в культуре (художественное творчество, архитектура, строительство, парковый, ландшафтный и интерьерный дизайн и т.д.).

Пионеры Возрождения Пачоли и Леонардо да Винчи («Тайная вечеря» и «Мона Лиза» вписаны в геометрические фигуры) обратили свое внимание на античность, где еще в «Началах» Евклид (ок. 300 лет до нашей эры) говорил о делении отрезка в крайнем и среднем отношении («ἄκρος καὶ μέσος λόγος»), полагая, что на числах построено все мироздание, на идеи Витрувия (ок. 80-70 гг. до нашей эры — после 13 г. до нашей эры), изложенные в «Десяти книгах об архитектуре» (лат. «De architectura libri decem») о применении математики к искусству архитектуры.

Пропорции золотого сечения

О том, как высчитывать золотые пропорции, рассказал эксперт в сфере фотографии Ренат Мансуров.

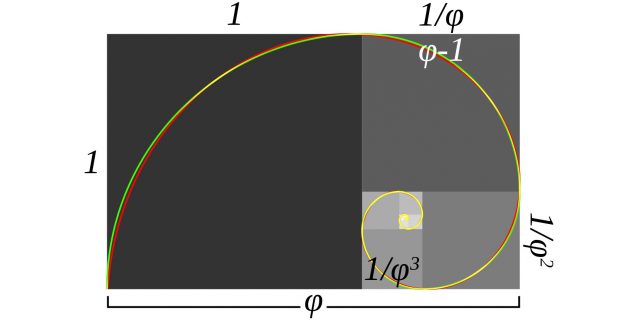

«Если взять для примера линию и разделить ее на две части так, чтобы длинная соотносилась с короткой в такой же пропорции, как вся линия соотносится с длинной, получится золотая пропорция», – поясняет он. К слову, она равна всегда 1,618, и это так называемое число «фи» обозначается греческой буквой φ — от имени древнегреческого скульптора Фидия.

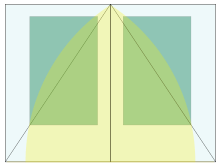

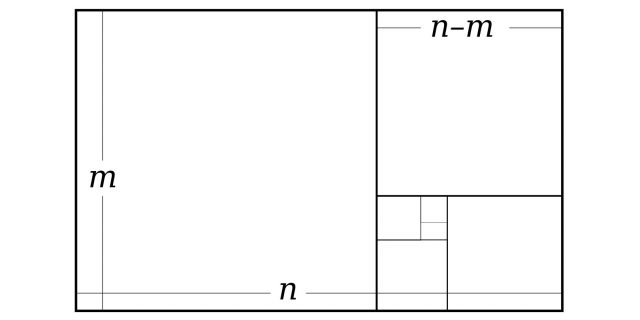

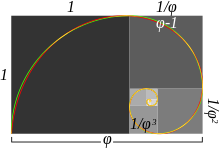

Ренат Мансуров отмечает, что в правильном прямоугольнике соотношение сторон соответствует золотому сечению.

«Интересен этот прямоугольник тем, что сколько бы ни отрезали от него квадратов, он всегда будет оставлять после себя кусочек с золотым соотношением сторон и так до бесконечности», – говорит Ренат Мансуров.

Золотое сечение в математике

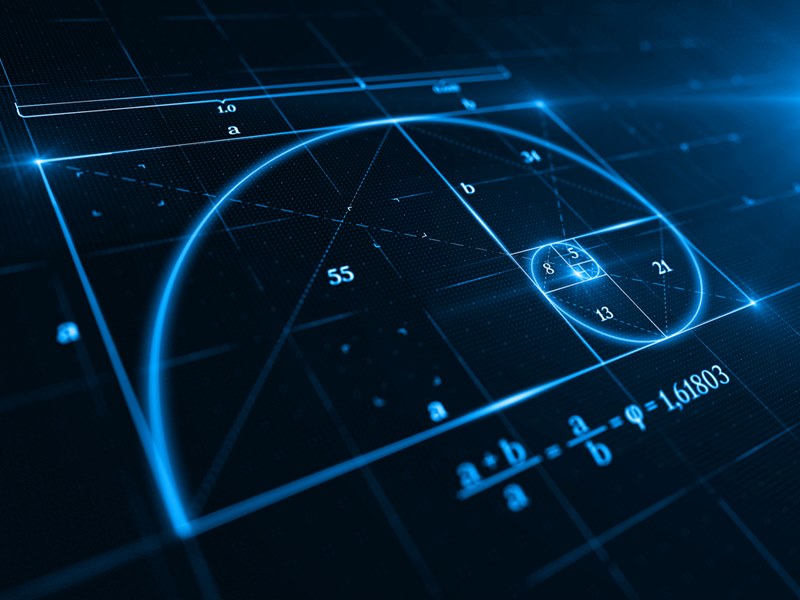

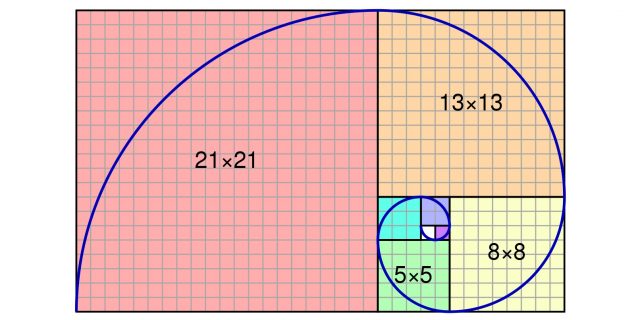

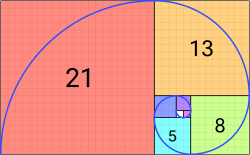

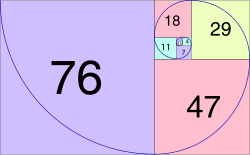

Итальянский астроном и математик Фибоначчи вывел ряд чисел, в котором значение каждого последующего равно сумме двух предыдущих. Эта закономерность известна как ряд Фибоначчи.

«Если представить два квадрата, поставленных рядом, потом добавить квадрат с удвоенной стороной, то получится квадрат 2 на 2. Далее добавить по спирали против часовой стрелки сумму двух предыдущих квадратов. Получится квадрат с длинной стороны три квадрата, далее добавить к стороне квадрата предыдущую сторону, получится 5, потом 8 потом 13 и 21, каждое последующее число — это сумма сложения с предыдущим, то есть получается такая последовательность, которую и вывел Фибоначчи: 0,1,1,2,3,5,8,13,21 и т.д.», – поясняет Ренат Мансуров.

0, 1,1 (0+1), 2 (1+1), 3 (1+2), 5 (2+3), 8 (3+5), 13 (5+8), 21 (8+13), 34 (13+21), 55 (21+34), 89 (34+55) и до бесконечности. А при делении последующего числа на предыдущее получается коэффициент золотого сечения. По мере возрастания чисел соотношение приближается к 1,618. К примеру, числа 3 и 5, их соотношение равно 1,666, а если взять 13 и 21, то получается уже 1,625. Данную формулу применяют для расчета пропорций золотого сечения в любой отрасли, на практике чаще всего используют округленное значение 0,62.

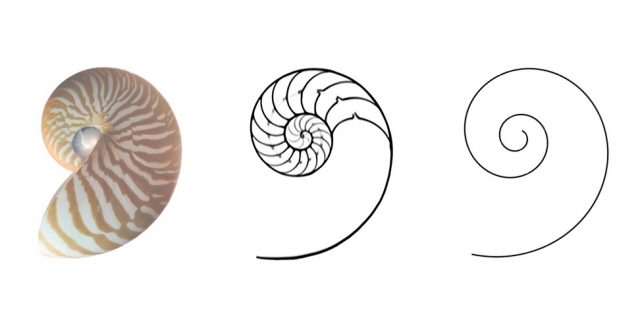

А если в каждом квадрате построить дугу из одного угла к другому, то получится так называемая спираль Фибоначчи.

Правило золотого сечения

На практике золотое сечение представляет собой пропорцию, соотношение сторон прямоугольника, отрезков определенной длины, других геометрических форм или сопряженных размерных характеристик реальных объектов.

Метод золотого сечения

«Если построить прямоугольник, используя метод, указанный выше, и встроить в этот прямоугольник линии, используя числа золотого сечения, то получится разграничение прямоугольника несколькими линиями. И если говорить о композиции, то размещая объекты на линиях или их пересечениях, можно максимально выделить эти объекты как смысловые центры, и наоборот, чем дальше от этих точек, тем труднее будет улавливать смысловой центр», – поясняет Ренат Мансуров.

Если же совместить спираль Фибоначчи и эту сетку, то получится практически инструкция по использованию золотого сечения в фотографии, живописи и дизайне.

Где можно увидеть золотое сечение

Если разделить обычное куриное яйцо мысленно пополам в самой широкой его части, то получатся правильные золотые пропорции. Пропорции здания Парфенона в Греции, спирали раковин, пропорции тела человека, спиральные галактики и растения, и еще много всего вокруг.

Природа

«

По словам Рената Мансурова, примеров этих золотых чисел и спиралей найти в природе можно множество. «Распределение семян подсолнуха, спиральные раковины, спиральные галактики, соотношения пропорций человеческого тела, и например, если внимательно посмотреть на нераскрытую еловую шишку или ананас с торца, то можно увидеть эти спирали», – отмечает эксперт.

Свою точку зрения озвучил Максим Господинко.

«У растения есть важная задача — наиболее оптимально расположить свои листья или лепестки, для того чтобы уловить больше солнечного света или просто уместить больше семян. В некоторых случаях есть возможность делать это только по плотной спирали (ананас, еловая шишка, подсолнечник). Кажется, что перед таким растением стоит сложная математическая задача — на какой угол сдвинуть следующую семечку или лепесток, но на самом деле вопрос лишь в том, насколько сильное создается отталкивание от уже существующего элемента.

И так складывается, что угол отклонения от предыдущего листка действительно очень близок к отношению «фи», – комментирует эксперт. – Ни одно рациональное отношение не подходит, потому что при повороте под такими углами возникают колонны-лучи с большими дырами, а как мы знаем, семена подсолнечника уложены красивыми спиралями, число которых как раз соответствует числам из ряда Фибоначчи и дыр там никаких нет».

По словам Максима Господинко, ряд Фибоначчи можно легко образовать, взяв ноль и единицу, а каждое последующее за ними получить из суммы двух предыдущих. «Моделировать растение конечно не умеет, насколько мне известно, и не знает количества рядов спиралей, а усилие отталкивания следующего элемента регулируется поколениями и естественным отбором, но в итоге приходит именно к “фи”», – отмечает специалист.

Названы знаменитости с идеальными пропорциями лица

Человек

Пропорции золотого сечения прослеживаются и на примере тела человека. К золотой формуле приравнивается абсолютно все: кости, ладони и пальцы, пропорции участков на лице, расстояние вытянутых рук по отношению к телу. Пропорции таковы:

- от плеч до макушки к размеру головы = 1:1.618

- от подбородка до верхней губы и от нее до носа = 1:1.618

- от пупка до макушки к отрезку от плеч до макушки = 1:1.618

- от пупка до колен и от колен до ступней = 1:1.618

Искусство

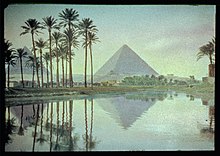

Пирамида Хеопса – единственное сохранившееся классическое чудо света

Множество произведений искусства и архитектурных шедевров сделаны по принципам золотого сечения. Египетские и пирамиды Майя, греческий Парфенон и так далее. Картины известных художников тоже выполнены с учетом правил золотого сечения.

Прослеживаются такие пропорции и в музыкальных произведениях Шуберта, Моцарта, Баха, Шопена и прочих.

«Для дизайнера и художника вопрос о золотом сечении стоит лишь в разрезе более широкой темы — пропорционирования. Не каждый использует этот инструмент, хоть и должен, но часто амбициозный художник, схватившись за “божественную истину”, начинает транслировать лишь её, упуская суть художественного высказывания, передачу образа. Пропорция – лишь инструмент и, очевидно, инструмент не должен идти вперёд задачи. Если образ не понят художником, его невозможно передать», – говорит Максим Господинко. Но тем не менее, переоценить важность этой пропорции сложно. Часто чувствительный художник сам интуитивно может расположить элементы в соответствии с “фи”, также оно является достаточно простым инструментом, чтобы создать изящную композицию даже в самых простых вещах.

Примеры использования в живописи.

© Public DomainКартина Леонардо Да Винчи «Мона Лиза»

Картина Леонардо Да Винчи «Мона Лиза»

1 из 2

Репродукция картины «Девочка на шаре» 1905 г. работы Пабло Пикассо, выставленная в Государственном музее изобразительных искусств им. А.С. Пушкина.

2 из 2

Картина Леонардо Да Винчи «Мона Лиза»

1 из 2

Репродукция картины «Девочка на шаре» 1905 г. работы Пабло Пикассо, выставленная в Государственном музее изобразительных искусств им. А.С. Пушкина.

2 из 2

Примеры использования золотого сечения в дизайне логотипов.

Логотип социальной сети Twitter на экранах мобильного телефона и компьютера.

1 из 2

Логотип компании Apple на стене фирменного магазине на 5-й авеню в Нью-Йорке.

2 из 2

Логотип социальной сети Twitter на экранах мобильного телефона и компьютера.

1 из 2

Логотип компании Apple на стене фирменного магазине на 5-й авеню в Нью-Йорке.

2 из 2

Применение золотого сечения

Примеры пропорции золотого сечения можно видеть при строительстве многих архитектурных сооружений и создании проекта дома, в современном дизайне интерьера при планировании и зонировании пространства, расстановки мебели и даже цветовом оформлении, а также в ландшафтном дизайне при выкладке закрученных дорожек, расположении растений на клумбах и других элементов.

Так, к примеру, при строительстве квартир и домов отношение самой большой комнаты к площади всей квартиры равно как 0,62 к 1, меньшее помещение делают с таким же соотношением к площади большей комнаты. Так, кухня – к меньшей комнате, прихожая к кухне, санузел к прихожей, а балкон – к санузлу.

Кроме того, с помощью золотого сечения подбирают и цветовое оформление. В интерьере применяют соотношение 10-30-60, основанное на золотом сечении. В пространстве используют три основных цвета: первый – доминирующий, охватывает 60% комнаты (стены и пол). Второй оттенок составляет 30% – мебель. И третий, 10%, приходится на декор.

«

«Существует множество вариантов золотого сечения. Но все они, так или иначе, основаны на числах Фибоначчи. Какие то из них популярны, какие то не очень, но о чем мы говорим сегодня, это то, что выработалось за последние столетия — это явно золотой стандарт, – говорит Ренат Мансуров. – Конечно, нужно понимать, что творчество остается творчеством и отходить от стандарта не возбраняется, но и совсем идти наперекор этим пропорциям не стоит».

По мнению эксперта, теория золотого сечения и «божественных пропорций» довольно популярна, но наука не стоит на месте, и сейчас активно исследуются теории восприятия с научной точки зрения. «То, что работает на практике не одно столетие, однозначно должно напоминать каждый раз о том, что эти пропорции проверены временем и сотнями тысяч творческих людей: фотографы, художники, дизайнеры и архитекторы каждый день работают и используют золотые пропорции в своей работе.

Реальная Вавилонская башня и первая пирамида: самые старые строения в мире

Высчитывать миллиметры и микроны в надежде сделать ваше творчество золотым, наверное, не стоит, но и забывать о приятных для глаза пропорциях наверняка не нужно», – говорит Ренат Мансуров.

Как это делать правильно, каждый решает самостоятельно, существует множество приемов композиции и работы с психологией восприятия, которые вместе могут улучшить работу в разы. «Учитесь правильно и не останавливайтесь в изучении художественных и композиционных приемов, и ваше творчество будет сиять оригинальностью и легкостью восприятия», – советует Ренат Мансуров.

Второе золотое сечение

Второе золотое сечение вытекает из основного сечения и дает отношение 44: 56.

Максим Господинко отмечает, что золотое сечение – не единственная пропорция, приятная глазу человека, есть “серебряное сечение”. Две величины находятся в «серебряном сечении», если отношение суммы меньшей и удвоенной большей величины к большей то же самое, что и отношение большей величины к меньшей. Также можно отметить, что порядок разлинованной в клетку тетради приятнее полного хаоса чистого листа (если не брать пропорцию самого его формата за порядок).

По словам эксперта, пропорция тетрадки в клетку ничем не хуже золотого сечения, но действие на человека она оказывает иное, как будто организуя простейший порядок — один к одному. «Если бы мы использовали такой поворот угла в подсолнухе, то получили бы одну линию семян, в случае с 1/4 — крест. Каждой задаче — свое решение. В случае с растениями им нужно как раз самое иррациональное число. Примечательно, что именно такое число и прослыло божественным», – говорит Максим Господинко.

Мифы о золотом сечении

«Можно спекулировать на тему того, что где-то в глубине восприятия человека лежит именно закономерность ряда Фибоначчи, вероятно, где-то мы так же решали геометрическую задачу поворота на нужный угол по спирали, может быть, всё живое, так или иначе помнит этот опыт. Но чтобы не очаровываться золотым сечением чрезмерно, можно обратить внимание на любовь человека к зигзагам и орнаментам. Далеко не обязательно строить бабушкин ковёр по “фи”, чтобы на него было приятнее смотреть, чем на голую стену, – считает Максим Господинко. – Оказывается, этот вид визуального комфорта обусловлен строением визуального кортекса человеческого мозга, и такие орнаменты, как мы можем увидеть в традиционных культурах, ложатся в него как недостающий кусочек удобного паззла вместо хаотичного визуального потока внешней среды. Резной наличник лучше голых ставень. Кружева лучше минимализма. Природа лучше асфальта. Потому что экономят ресурсы человека, показывая привычные и близкие формы».

Что такое золотое сечение и правда ли оно повсюду

Спойлер: это лишь красивая математическая легенда.

Что такое золотое сечение

Это соотношение двух неравных чисел, при котором большее так же относится к меньшему, как сумма этих чисел к большему. Золотое сечение равно примерно 1,618, или 1,62, если округлить, и обозначается греческой буквой φ, «фи» — от имени древнегреческого скульптора Фидия. Считается, что он использовал такие пропорции при оформлении Парфенона.

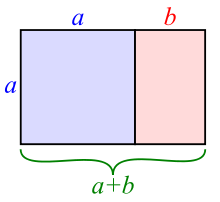

Наиболее известные графические представления золотого сечения — это прямоугольник с соотношением сторон примерно 62:48 и построенная в нём спираль.

1 / 0

«Золотой прямоугольник» можно разделить на такие же, только меньшего размера. Изображение: Dicklyon / Wikimedia Commons

2 / 0

«Золотая спираль» (красная), вписанная в «золотой прямоугольник». Изображение: Silverhammermba & Jahobr / Wikimedia Commons

Золотое сечение тесно связано с числами Фибоначчи. Это ряд чисел, каждое из которых равняется сумме двух предыдущих: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34 и так далее. Чем дальше продолжается этот ряд, тем ближе соотношение соседних чисел в нём к 1,618. Например, 3/2=1,5; 8/5=1,6, а 34/21= 1,619.

Почему золотое сечение так популярно

Впервые им заинтересовались ещё древнегреческие математики Пифагор и Евклид. Они считали, что на числах построено всё мироздание и с их помощью можно объяснить любой феномен. Неудивительно, что элегантное соотношение так заинтересовало античных мыслителей.

Вслед за ними золотым сечением увлеклись многие выдающиеся учёные и деятели искусства. Например, Леонардо да Винчи, Альбрехт Дюрер, Иоганн Кеплер, Ле Корбюзье, Сальвадор Дали и Ричард Пенроуз.

Его считают «божественной пропорцией»

Название «золотое сечение» придумал немецкий математик XIX века Мартин Ом. До него это соотношение именовали «божественной пропорцией».

Из‑за приписываемых характеристик золотое сечение старались применять как можно чаще. Так, во времена Возрождения это число считалось идеальным способом для выбора размера. «Золотой прямоугольник», например, нередко использовали при создании книг и картин. А линию пояса называли границей золотого сечения человеческого тела.

Некоторые и поныне считают эту пропорцию секретом привлекательности и примером универсальной гармонии, приятной человеческому глазу. Например, о золотом сечении любят говорить пластические хирурги. А ещё это число популярно как никакое другое в математике.

Его можно встретить в природе

Числа Фибоначчи и спирали, подобные золотому сечению, часто обнаруживаются в природе. Например, в количестве лепестков у цветов или форме растений.

Его обнаруживают в произведениях архитектуры и искусства

Например, «божественные пропорции» находят в Парфеноне и египетских пирамидах. Также широко распространено заблуждение, что «Мона Лиза» написана в соответствии с числом φ.

Почему универсальность золотого сечения — миф

Однако при тщательном изучении становится понятно, что эта пропорция не так уж всеобъемлюща.

Божественность золотого сечения преувеличивается

Золотому сечению придают больше значения, чем есть в действительности. Красивые узоры и налёт таинственности сделали из обычного геометрического соотношения математический миф, который, к примеру, очень любят нумерологи.

Чаще всего вещи причисляют к золотому сечению с большими допущениями. Ни о какой точности и математической универсальности в таком случае говорить не приходится. Поэтому при желании можно обнаружить «божественные пропорции» где угодно.

В природе золотое сечение не так уж распространено

Его находят далеко не везде. Например, у маков всегда четыре лепестка, а в ряд Фибоначчи четвёрка не входит. Также нередко встречается четырёхлистный клевер. Раковины морских моллюсков похожи на спираль золотого сечения, но всё-таки другие. У них больше витков, и расстояние между ними меньше. Ни у одного моллюска коэффициент скручивания раковины и близко не равен 1,62. Это видно даже невооружённым глазом:

1 / 0

Спираль морского моллюска. Изображение: Florian Elias Rieser / Wikimedia Commons

2 / 0

Спираль Фибоначчи, близкая к золотому сечению. Изображение: Jahobr / Wikimedia Commons

В человеческом теле же столько точек, от которых можно производить измерение, что при желании реально найти золотое сечение где угодно. Вот только с большой вероятностью у разных людей «божественную пропорцию» придётся искать в разных местах, так как мы можем сильно отличаться друг от друга.

В искусстве оно тоже встречается не так уж часто

Изучение 565 картин выдающихся художников показало, что в среднем соотношение сторон в работах составляет 1,34. Это явно не дотягивает до золотого сечения. Учёные не находят его даже в произведениях Леонардо да Винчи.

Археологические исследования не подтверждают и того, что древние греки могли использовать золотое сечение при постройке Парфенона. Из более чем 100 памятников древнегреческой архитектуры это число нашлось в пропорциях только четырёх объектов: башни, алтаря, гробницы и надгробия. Не могли пользоваться золотым сечением и древние египтяне, не обладавшие достаточным уровнем технологий, чтобы точно высчитывать пропорции.

Кому золотое сечение может быть полезно на самом деле

Современная математика использует золотое сечение и числа Фибоначчи при описании фракталов — фигур, которые проявляют самоподобие.

Знание о числе φ играет важную роль в изучении хаоса и изменяющихся (динамических) систем. Оно помогает понять, как природа развивается и самоорганизуется.

Также числа Фибоначчи полезны при решении некоторых сложных задач. Например, с помощью этих чисел советский математик Юрий Матиясевич доказал, что не существует универсального алгоритма решения уравнений с как минимум двумя неизвестными.

Читайте также 💆♂️👩🔬

- Продолжите последовательность! 10 мини-задач для разминки мозга

- Как округлять числа

- Интересные математические факты для тех, кто хочет больше узнать о мире вокруг

- Гимнастика для ума: 10 увлекательных задач с числами

- 10 увлекательных задач от советского математика

Число Ф (фи), которое называют золотым сечением или серединой, является одним из самых загадочных терминов в математике и физике. Интересно, что оно часто встречается в повседневной жизни, хотя многие об этом никогда не задумывались. Даже люди, не знакомые с правилом золотого сечения, видят его, сами того не понимая. Проводились эксперименты: испытуемым показывали случайные лица и просили назвать наиболее привлекательные. Таковыми оказывались лица, в которых находили золотые соотношения между различными величинами – шириной лица, глаз, линии бровей, носа. Таким образом, инстинктивно человек видит приближенное к пропорциям, которые считаются идеальными.

Содержание:

- 1 Что такое золотое сечение?

- 2 История золотого сечения

- 3 «Золотые» фигуры

- 4 Золотое сечение в изобразительном искусстве

- 5 Примеры золотого сечения в жизни и в природе

Что такое золотое сечение?

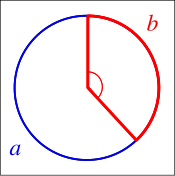

Это пропорция, полученная делением в крайнем и среднем отношении. Также это называют гармоническим делением. Как вычисляется золотая середина? В выражении математическим языком эта величина представляет собой соотношение двух величин a и b, где известно, что а>b, и имеет место такое равенство: a/b=(a+b)/a. Представив, что a и b – это части одного отрезка, можно сказать: отношение меньшей части к большей равно отношению большей части к целому. Золотое сечение обозначают 21-й буквой греческого алфавита – Ф (произносится как «фи»).

Данное число бесконечно, как и Пи, показывающее отношение длины окружности к диаметру. Выглядит оно так: 1.6180339887498948420… Соответственно, округляют Ф до 1,618.

История золотого сечения

У этой величины несколько названий. Среди них – божественная пропорция и асимметричная симметрия. Считается, что в науку метод золотого деления внес Пифагор в VI веке до нашей эры. В свою очередь он узнал об этом у египтян и вавилонян. Ведь то, что они использовали соотношения золотого деления доказывают пропорции пирамид, храмов, барельефов, предметов быта и украшений.

Встречается данное правило и в другой древней архитектуре. Например, пирамида Гизы имеет высоту 146,6 метров, а каждая сторона основания достигает 230,5 метров. Если рассчитать отношение длины стороны к высоте, получаем 1,5717, а это совсем рядом со значением Ф. Греческий скульптор и математик Фидий, живший в V веке до нашей эры с применением правила золотого деления создавал скульптуры для Парфенона. Универсальным связующим звеном математических отношений назвал золотое сечение Платон. А Евклид еще в IV веке до нашей эры увидел золотое сечение в пентаграмме.

С данным понятием непосредственно связана последовательность Фибоначчи. Известный математик создал последовательный ряд чисел, и если взять любые два очередных числа, то их отношение будет очень близко к Ф. При этом по мере возрастания чисел, соотношение всё больше приближается к 1,618. К примеру, если взять 3 и 5, то соотношение равно 1,666, а если 13 и 21, то получается уже 1,625. Равное значению Ф дает отношение 144 и 233.

«Золотые» фигуры

Принцип золотого сечения используется для построения геометрических фигур. И считается, что полученные таким образом фигуры, выглядят наиболее изящными. Это подтверждают многократно проведенные эксперименты. Внимание испытуемых больше привлекают именно такие фигуры.

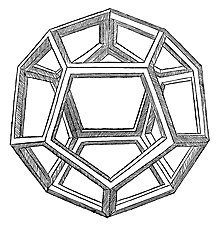

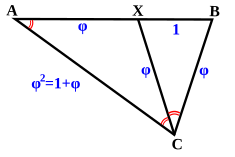

Самым простым примером является прямоугольник, при вычислении отношения сторон которого получаем значение Ф. Еще один замечательный пример – правильный пятиугольник. Все его диагонали делят друг друга на отрезки, связанные золотой пропорцией, а каждый конец – это золотой треугольник. При вершине такого треугольника образуется угол в 36 градусов, а основание делит боковую сторону в пропорции золотого сечения. Внутри пятиугольника строится пентаграмма.

Древнегреческий ученый Архимед, первым отметил, что если от золотого прямоугольника последовательно отсекать квадраты, соединяя противоположные точки четвертью окружности, получается изящная спираль.

Золотое сечение в изобразительном искусстве

В эпоху Возрождения при создании картин и скульптур великие мастера применяли золотое сечение, чтобы достичь баланс красоты. Наиболее яркими примерами являются творения Леонардо да Винчи. С помощью этого правила художник определял пропорции в работе «Тайная вечеря». Это видно при исследовании размеров стола, стен, элементов интерьера. Также божественная пропорция прослеживается в картинах «Мона Лиза» и «Витрувианский Человек». Такие великие художники, как Микеланджело, Рафаэль, Рембрандт, Сальвадор Дали и другие, использовали золотое сечение при создании своих шедевров.

Примеры золотого сечения в жизни и в природе

Ежедневно мы можем наблюдать идеальные пропорции:

- Грудная и брюшная части тела бабочки соотносятся в золотой пропорции. А при сложенных крыльях это прекрасное создание представляет собой правильный треугольник с равными сторонами.

- У стрекозы длины хвоста и корпуса относятся так же, как общая длина тела к хвосту.

- В пропорциях тела ящерицы также прослеживается данный принцип.

- Большинство яиц птиц можно вписать в золотой прямоугольник.

- Последовательность Фибоначчи видна в развитии растений, в расположении чешуек в шишках, зерен в подсолнухах.

- Спирально растет бараний рог, плетет паутину паук.

- Интересно, что если напугать стадо северных оленей, то животные будут разбегаться по спирали.

- В форме двойной спирали представлена молекула ДНК.

- Цветки разных растений, а также морские звезды имеют форму правильного пятиугольника.

Как видно, примеров с правильными пропорциями в природе и повседневной жизни предостаточно. Не даром золотое сечение называют божественной пропорцией. Вероятно, именно этим правилом руководствовался создатель в процессе заполнения Вселенной живыми и неживыми объектами. То, что соответствует этому правилу, кажется нам наиболее привлекательным.

В мире много интересных вещей, изучение нового делает нас умнее, способствует развитию мозга и мышления. Советуем вам обязательно находить время на познание нового. А чтобы было легче усваивать и запоминать большие объемы информации, рекомендуем тренажеры Викиум. Регулярно используя их для тренировок мозга, вы сможете улучшить память, внимательность, логику и аналитические способности.

Line segments in the golden ratio |

|

| Representations | |

|---|---|

| Decimal | 1.618033988749894…[1] |

| Algebraic form |  |

| Continued fraction |  |

| Binary | 1.10011110001101110111… |

| Hexadecimal | 1.9E3779B97F4A7C15… |

A golden rectangle with long side a and short side b (shaded red, right) and a square with sides of length a (shaded blue, left) combine to form a similar golden rectangle with long side a + b and short side a. This illustrates the relationship

In mathematics, two quantities are in the golden ratio if their ratio is the same as the ratio of their sum to the larger of the two quantities. Expressed algebraically, for quantities

where the Greek letter phi (

The golden ratio was called the extreme and mean ratio by Euclid,[2] and the divine proportion by Luca Pacioli,[3] and also goes by several other names.[b]

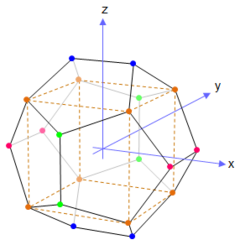

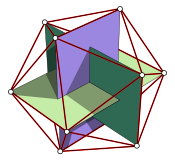

Mathematicians have studied the golden ratio’s properties since antiquity. It is the ratio of a regular pentagon’s diagonal to its side and thus appears in the construction of the dodecahedron and icosahedron.[7] A golden rectangle—that is, a rectangle with an aspect ratio of

Some 20th-century artists and architects, including Le Corbusier and Salvador Dalí, have proportioned their works to approximate the golden ratio, believing it to be aesthetically pleasing. These uses often appear in the form of a golden rectangle.

Calculation

Two quantities

One method for finding a closed form for

Therefore,

Multiplying by

which can be rearranged to

The quadratic formula yields two solutions:

Because

History

According to Mario Livio,

Some of the greatest mathematical minds of all ages, from Pythagoras and Euclid in ancient Greece, through the medieval Italian mathematician Leonardo of Pisa and the Renaissance astronomer Johannes Kepler, to present-day scientific figures such as Oxford physicist Roger Penrose, have spent endless hours over this simple ratio and its properties. … Biologists, artists, musicians, historians, architects, psychologists, and even mystics have pondered and debated the basis of its ubiquity and appeal. In fact, it is probably fair to say that the Golden Ratio has inspired thinkers of all disciplines like no other number in the history of mathematics.[11]

— The Golden Ratio: The Story of Phi, the World’s Most Astonishing Number

Ancient Greek mathematicians first studied the golden ratio because of its frequent appearance in geometry;[12] the division of a line into «extreme and mean ratio» (the golden section) is important in the geometry of regular pentagrams and pentagons.[13] According to one story, 5th-century BC mathematician Hippasus discovered that the golden ratio was neither a whole number nor a fraction (it is irrational), surprising Pythagoreans.[14] Euclid’s Elements (c. 300 BC) provides several propositions and their proofs employing the golden ratio,[15][c] and contains its first known definition which proceeds as follows:[16]

A straight line is said to have been cut in extreme and mean ratio when, as the whole line is to the greater segment, so is the greater to the lesser.[17][d]

The golden ratio was studied peripherally over the next millennium. Abu Kamil (c. 850–930) employed it in his geometric calculations of pentagons and decagons; his writings influenced that of Fibonacci (Leonardo of Pisa) (c. 1170–1250), who used the ratio in related geometry problems but did not observe that it was connected to the Fibonacci numbers.[19]

Luca Pacioli named his book Divina proportione (1509) after the ratio; the book, largely plagiarized from Piero della Francesca, explored its properties including its appearance in some of the Platonic solids.[20][21] Leonardo da Vinci, who illustrated Pacioli’s book, called the ratio the sectio aurea (‘golden section’).[22] Though it is often said that Pacioli advocated the golden ratio’s application to yield pleasing, harmonious proportions, Livio points out that the interpretation has been traced to an error in 1799, and that Pacioli actually advocated the Vitruvian system of rational proportions.[23] Pacioli also saw Catholic religious significance in the ratio, which led to his work’s title. 16th-century mathematicians such as Rafael Bombelli solved geometric problems using the ratio.[24]

German mathematician Simon Jacob (d. 1564) noted that consecutive Fibonacci numbers converge to the golden ratio;[25] this was rediscovered by Johannes Kepler in 1608.[26] The first known decimal approximation of the (inverse) golden ratio was stated as «about

Geometry has two great treasures: one is the theorem of Pythagoras, the other the division of a line into extreme and mean ratio. The first we may compare to a mass of gold, the second we may call a precious jewel.[28]

18th-century mathematicians Abraham de Moivre, Nicolaus I Bernoulli, and Leonhard Euler used a golden ratio-based formula which finds the value of a Fibonacci number based on its placement in the sequence; in 1843, this was rediscovered by Jacques Philippe Marie Binet, for whom it was named «Binet’s formula».[29] Martin Ohm first used the German term goldener Schnitt (‘golden section’) to describe the ratio in 1835.[30] James Sully used the equivalent English term in 1875.[31]

By 1910, inventor Mark Barr began using the Greek letter phi (

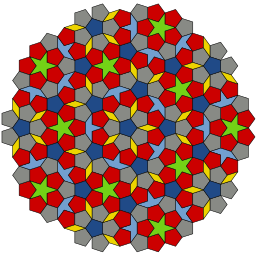

The zome construction system, developed by Steve Baer in the late 1960s, is based on the symmetry system of the icosahedron/dodecahedron, and uses the golden ratio ubiquitously. Between 1973 and 1974, Roger Penrose developed Penrose tiling, a pattern related to the golden ratio both in the ratio of areas of its two rhombic tiles and in their relative frequency within the pattern.[36] This gained in interest after Dan Shechtman’s Nobel-winning 1982 discovery of quasicrystals with icosahedral symmetry, which were soon afterward explained through analogies to the Penrose tiling.[37]

Mathematics

Irrationality

The golden ratio is an irrational number. Below are two short proofs of irrationality:

Contradiction from an expression in lowest terms

If φ were rational, then it would be the ratio of sides of a rectangle with integer sides (the rectangle comprising the entire diagram). But it would also be a ratio of integer sides of the smaller rectangle (the rightmost portion of the diagram) obtained by deleting a square. The sequence of decreasing integer side lengths formed by deleting squares cannot be continued indefinitely because the positive integers have a lower bound, so φ cannot be rational.

Recall that:

the whole is the longer part plus the shorter part;

the whole is to the longer part as the longer part is to the shorter part.

If we call the whole

To say that the golden ratio

By irrationality of √5

Another short proof – perhaps more commonly known – of the irrationality of the golden ratio makes use of the closure of rational numbers under addition and multiplication. If

Minimal polynomial

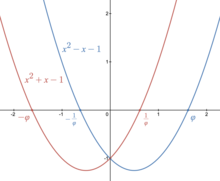

The golden ratio φ and its negative reciprocal −φ−1 are the two roots of the quadratic polynomial x2 − x − 1. The golden ratio’s negative −φ and reciprocal φ−1 are the two roots of the quadratic polynomial x2 + x − 1.

The golden ratio is also an algebraic number and even an algebraic integer. It has minimal polynomial

This quadratic polynomial has two roots,

The golden ratio is also closely related to the polynomial

which has roots

Golden ratio conjugate and powers

The conjugate root to the minimal polynomial

The absolute value of this quantity (

This illustrates the unique property of the golden ratio among positive numbers, that

or its inverse:

The conjugate and the defining quadratic polynomial relationship lead to decimal values that have their fractional part in common with

The sequence of powers of

any power of

As a result, one can easily decompose any power of

If

Continued fraction and square root

Approximations to the reciprocal golden ratio by finite continued fractions, or ratios of Fibonacci numbers

The formula

It is in fact the simplest form of a continued fraction, alongside its reciprocal form:

The convergents of these continued fractions (

This means that the constant

A continued square root form for

Relationship to Fibonacci and Lucas numbers

Fibonacci numbers and Lucas numbers have an intricate relationship with the golden ratio. In the Fibonacci sequence, each number is equal to the sum of the preceding two, starting with the base sequence

The sequence of Lucas numbers (not to be confused with the generalized Lucas sequences, of which this is part) is like the Fibonacci sequence, in-which each term is the sum of the previous two, however instead starts with

Exceptionally, the golden ratio is equal to the limit of the ratios of successive terms in the Fibonacci sequence and sequence of Lucas numbers:[42]

In other words, if a Fibonacci and Lucas number is divided by its immediate predecessor in the sequence, the quotient approximates

For example,

These approximations are alternately lower and higher than

Closed-form expressions for the Fibonacci and Lucas sequences that involve the golden ratio are:

Combining both formulas above, one obtains a formula for

Between Fibonacci and Lucas numbers one can deduce

Indeed, much stronger statements are true:

,

.

These values describe

Successive powers of the golden ratio obey the Fibonacci recurrence, i.e.

The reduction to a linear expression can be accomplished in one step by using:

This identity allows any polynomial in

Consecutive Fibonacci numbers can also be used to obtain a similar formula for the golden ratio, here by infinite summation:

In particular, the powers of

and so forth.[43] The Lucas numbers also directly generate powers of the golden ratio; for

Rooted in their interconnecting relationship with the golden ratio is the notion that the sum of third consecutive Fibonacci numbers equals a Lucas number, that is

Both the Fibonacci sequence and the sequence of Lucas numbers can be used to generate approximate forms of the golden spiral (which is a special form of a logarithmic spiral) using quarter-circles with radii from these sequences, differing only slightly from the true golden logarithmic spiral. Fibonacci spiral is generally the term used for spirals that approximate golden spirals using Fibonacci number-sequenced squares and quarter-circles.

Geometry

The golden ratio features prominently in geometry. For example, it is intrinsically involved in the internal symmetry of the pentagon, and extends to form part of the coordinates of the vertices of a regular dodecahedron, as well as those of a 5-cell. It features in the Kepler triangle and Penrose tilings too, as well as in various other polytopes.

Construction

Dividing a line segment by interior division (top) and exterior division (bottom) according to the golden ratio.

Dividing by interior division

- Having a line segment

construct a perpendicular

at point

with

half the length of

Draw the hypotenuse

- Draw an arc with center

and radius

This arc intersects the hypotenuse

at point

- Draw an arc with center

and radius

This arc intersects the original line segment

at point

Point

divides the original line segment

into line segments

and

with lengths in the golden ratio.

Dividing by exterior division

- Draw a line segment

and construct off the point

a segment

perpendicular to

and with the same length as

- Do bisect the line segment

with

- A circular arc around

with radius

intersects in point

the straight line through points

and

(also known as the extension of

). The ratio of

to the constructed segment

is the golden ratio.

Application examples you can see in the articles Pentagon with a given side length, Decagon with given circumcircle and Decagon with a given side length.

Both of the above displayed different algorithms produce geometric constructions that determine two aligned line segments where the ratio of the longer one to the shorter one is the golden ratio.

Golden angle

When two angles that make a full circle have measures in the golden ratio, the smaller is called the golden angle, with measure

This angle occurs in patterns of plant growth as the optimal spacing of leaf shoots around plant stems so that successive leaves do not block sunlight from the leaves below them.[44]

Pentagonal symmetry system

Pentagon and pentagram

A pentagram colored to distinguish its line segments of different lengths. The four lengths are in golden ratio to one another.

In a regular pentagon the ratio of a diagonal to a side is the golden ratio, while intersecting diagonals section each other in the golden ratio. The golden ratio properties of a regular pentagon can be confirmed by applying Ptolemy’s theorem to the quadrilateral formed by removing one of its vertices. If the quadrilateral’s long edge and diagonals are

The diagonal segments of a pentagon form a pentagram, or five-pointed star polygon, whose geometry is quintessentially described by

Pentagonal and pentagrammic geometry permits us to calculate the following values for

Golden triangle and golden gnomon

A golden triangle ABC can be subdivided by an angle bisector into a smaller golden triangle CXB and a golden gnomon XAC.

The triangle formed by two diagonals and a side of a regular pentagon is called a golden triangle or sublime triangle. It is an acute isosceles triangle with apex angle 36° and base angles 72°.[45] Its two equal sides are in the golden ratio to its base.[46] The triangle formed by two sides and a diagonal of a regular pentagon is called a golden gnomon. It is an obtuse isosceles triangle with apex angle 108° and base angle 36°. Its base is in the golden ratio to its two equal sides.[46] The pentagon can thus be subdivided into two golden gnomons and a central golden triangle. The five points of a regular pentagram are golden triangles,[46] as are the ten triangles formed by connecting the vertices of a regular decagon to its center point.[47]

Bisecting one of the base angles of the golden triangle subdivides it into a smaller golden triangle and a golden gnomon. Analogously, any acute isosceles triangle can be subdivided into a similar triangle and an obtuse isosceles triangle, but the golden triangle is the only one for which this subdivision is made by the angle bisector, because it is the only isosceles triangle whose base angle is twice its apex angle. The angle bisector of the golden triangle subdivides the side that it meets in the golden ratio, and the areas of the two subdivided pieces are also in the golden ratio.[46]

If the apex angle of the golden gnomon is trisected, the trisector again subdivides it into a smaller golden gnomon and a golden triangle. The trisector subdivides the base in the golden ratio, and the two pieces have areas in the golden ratio. Analogously, any obtuse triangle can be subdivided into a similar triangle and an acute isosceles triangle, but the golden gnomon is the only one for which this subdivision is made by the angle trisector, because it is the only isosceles triangle whose apex angle is three times its base angle.[46]

Penrose tilings

The kite and dart tiles of the Penrose tiling. The colored arcs divide each edge in the golden ratio; when two tiles share an edge, their arcs must match.

The golden ratio appears prominently in the Penrose tiling, a family of aperiodic tilings of the plane developed by Roger Penrose, inspired by Johannes Kepler’s remark that pentagrams, decagons, and other shapes could fill gaps that pentagonal shapes alone leave when tiled together.[48] Several variations of this tiling have been studied, all of whose prototiles exhibit the golden ratio:

- Penrose’s original version of this tiling used four shapes: regular pentagons and pentagrams, «boat» figures with three points of a pentagram, and «diamond» shaped rhombi.[49]

- The kite and dart Penrose tiling uses kites with three interior angles of 72° and one interior angle of 144°, and darts, concave quadrilaterals with two interior angles of 36°, one of 72°, and one non-convex angle of 216°. Special matching rules restrict how the tiles can meet at any edge, resulting in seven combinations of tiles at any vertex. Both the kites and darts have sides of two lengths, in the golden ratio to each other. The areas of these two tile shapes are also in the golden ratio to each other.[48]

- The kite and dart can each be cut on their symmetry axes into a pair of golden triangles and golden gnomons, respectively. With suitable matching rules, these triangles, called in this context Robinson triangles, can be used as the prototiles for a form of the Penrose tiling.[48][50]

- The rhombic Penrose tiling contains two types of rhombus, a thin rhombus with angles of 36° and 144°, and a thick rhombus with angles of 72° and 108°. All side lengths are equal, but the ratio of the length of sides to the short diagonal in the thin rhombus equals

, as does the ratio of the sides of to the long diagonal of the thick rhombus. As with the kite and dart tiling, the areas of the two rhombi are in the golden ratio to each other. Again, these rhombi can be decomposed into pairs of Robinson triangles.[48]

Original four-tile Penrose tiling

Rhombic Penrose tiling

In triangles and quadrilaterals

Odom’s construction

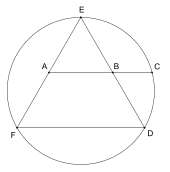

Odom’s construction: AB : BC = AC : AB = φ : 1

George Odom found a construction for

Kepler triangle

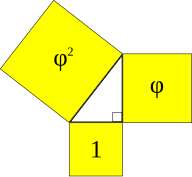

Geometric progression of areas of squares on the sides of a Kepler triangle

An isosceles triangle formed from two Kepler triangles maximizes the ratio of its inradius to side length

The Kepler triangle, named after Johannes Kepler, is the unique right triangle with sides in geometric progression:

These side lengths are the three Pythagorean means of the two numbers

Among isosceles triangles, the ratio of inradius to side length is maximized for the triangle formed by two reflected copies of the Kepler triangle, sharing the longer of their two legs.[52] The same isosceles triangle maximizes the ratio of the radius of a semicircle on its base to its perimeter.[53]

For a Kepler triangle with smallest side length

Golden rectangle

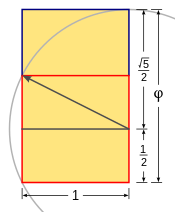

To construct a golden rectangle with only a straightedge and compass in four simple steps:

| Draw a square. |

| Draw a line from the midpoint of one side of the square to an opposite corner. |

| Use that line as the radius to draw an arc that defines the height of the rectangle. |

| Complete the golden rectangle. |

The golden ratio proportions the adjacent side lengths of a golden rectangle in

Golden rhombus

A golden rhombus is a rhombus whose diagonals are in proportion to the golden ratio, most commonly

The lengths of its short and long diagonals

Its area, in terms of

Its inradius, in terms of side

Golden rhombi feature in the rhombic triacontahedron (see section below). They also are found in the golden rhombohedron, the Bilinski dodecahedron,[57] and the rhombic hexecontahedron.[56]

Golden spiral

The golden spiral (red) and its approximation by quarter-circles (green), with overlaps shown in yellow

A logarithmic spiral whose radius grows by the golden ratio per 108° of turn, surrounding nested golden isosceles triangles. This is a different spiral from the golden spiral, which grows by the golden ratio per 90° of turn.[58]

Logarithmic spirals are self-similar spirals where distances covered per turn are in geometric progression. A logarithmic spiral whose radius increases by a factor of the golden ratio for each quarter-turn is called the golden spiral. These spirals can be approximated by quarter-circles that grow by the golden ratio,[59] or their approximations generated from Fibonacci numbers,[60] often depicted inscribed within a spiraling pattern of squares growing in the same ratio. The exact logarithmic spiral form of the golden spiral can be described by the polar equation with

Not all logarithmic spirals are connected to the golden ratio, and not all spirals that are connected to the golden ratio are the same shape as the golden spiral. For instance, a different logarithmic spiral, encasing a nested sequence of golden isosceles triangles, grows by the golden ratio for each 108° that it turns, instead of the 90° turning angle of the golden spiral.[58] Another variation, called the «better golden spiral», grows by the golden ratio for each half-turn, rather than each quarter-turn.[59]

In the dodecahedron and icosahedron

| Cartesian coordinates of the dodecahedron : | |

| (±1, ±1, ±1) | |

| (0, ±φ, ±1/φ) | |

| (±1/φ, 0, ±φ) | |

| (±φ, ±1/φ, 0) | |

| A nested cube inside the dodecahedron is represented with dotted lines. |

The regular dodecahedron and its dual polyhedron the icosahedron are Platonic solids whose dimensions are related to the golden ratio. An icosahedron is made of

For a dodecahedron of side

While for an icosahedron of side

The volume and surface area of the dodecahedron can be expressed in terms of

As well as for the icosahedron:

These geometric values can be calculated from their Cartesian coordinates, which also can be given using formulas involving

Sets of three golden rectangles intersect perpendicularly inside dodecahedra and icosahedra, forming Borromean rings.[62][55] In dodecahedra, pairs of opposing vertices in golden rectangles meet the centers of pentagonal faces, and in icosahedra, they meet at its vertices. In all, the three golden rectangles contain

A cube can be inscribed in a regular dodecahedron, with some of the diagonals of the pentagonal faces of the dodecahedron serving as the cube’s edges; therefore, the edge lengths are in the golden ratio. The cube’s volume is

Other polyhedra are related to the dodecahedron and icosahedron or their symmetries, and therefore have corresponding relations to the golden ratio. These include the compound of five cubes, compound of five octahedra, compound of five tetrahedra, the compound of ten tetrahedra, rhombic triacontahedron, icosidodecahedron, truncated icosahedron, truncated dodecahedron, and rhombicosidodecahedron, rhombic enneacontahedron, and Kepler-Poinsot polyhedra, and rhombic hexecontahedron. In four dimensions, the dodecahedron and icosahedron appear as faces of the 120-cell and 600-cell, which again have dimensions related to the golden ratio.

Other properties

The golden ratio’s decimal expansion can be calculated via root-finding methods, such as Newton’s method or Halley’s method, on the equation

In the complex plane, the fifth roots of unity

![{textstyle mathbb {Z} [varphi ].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6c19ab3d8278828be7f591bad1dc4482e4aaac6d)

This also holds for the remaining tenth roots of unity satisfying

For the gamma function

When the golden ratio is used as the base of a numeral system (see golden ratio base, sometimes dubbed phinary or

![{displaystyle mathbb {Z} [varphi ]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/14f984c2710477c64fca0f16a71928134bdb8201)

The golden ratio also appears in hyperbolic geometry, as the maximum distance from a point on one side of an ideal triangle to the closer of the other two sides: this distance, the side length of the equilateral triangle formed by the points of tangency of a circle inscribed within the ideal triangle, is

The golden ratio appears in the theory of modular functions as well. For

Then

and

where

Applications and observations

Architecture

The Swiss architect Le Corbusier, famous for his contributions to the modern international style, centered his design philosophy on systems of harmony and proportion. Le Corbusier’s faith in the mathematical order of the universe was closely bound to the golden ratio and the Fibonacci series, which he described as «rhythms apparent to the eye and clear in their relations with one another. And these rhythms are at the very root of human activities. They resound in man by an organic inevitability, the same fine inevitability which causes the tracing out of the Golden Section by children, old men, savages and the learned.»[70][71]

Le Corbusier explicitly used the golden ratio in his Modulor system for the scale of architectural proportion. He saw this system as a continuation of the long tradition of Vitruvius, Leonardo da Vinci’s «Vitruvian Man», the work of Leon Battista Alberti, and others who used the proportions of the human body to improve the appearance and function of architecture.

In addition to the golden ratio, Le Corbusier based the system on human measurements, Fibonacci numbers, and the double unit. He took suggestion of the golden ratio in human proportions to an extreme: he sectioned his model human body’s height at the navel with the two sections in golden ratio, then subdivided those sections in golden ratio at the knees and throat; he used these golden ratio proportions in the Modulor system. Le Corbusier’s 1927 Villa Stein in Garches exemplified the Modulor system’s application. The villa’s rectangular ground plan, elevation, and inner structure closely approximate golden rectangles.[72]

Another Swiss architect, Mario Botta, bases many of his designs on geometric figures. Several private houses he designed in Switzerland are composed of squares and circles, cubes and cylinders. In a house he designed in Origlio, the golden ratio is the proportion between the central section and the side sections of the house.[73]

Art

Leonardo da Vinci’s illustrations of polyhedra in Pacioli’s Divina proportione have led some to speculate that he incorporated the golden ratio in his paintings. But the suggestion that his Mona Lisa, for example, employs golden ratio proportions, is not supported by Leonardo’s own writings.[74] Similarly, although Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man is often shown in connection with the golden ratio, the proportions of the figure do not actually match it, and the text only mentions whole number ratios.[75][76]

Salvador Dalí, influenced by the works of Matila Ghyka,[77] explicitly used the golden ratio in his masterpiece, The Sacrament of the Last Supper. The dimensions of the canvas are a golden rectangle. A huge dodecahedron, in perspective so that edges appear in golden ratio to one another, is suspended above and behind Jesus and dominates the composition.[74][78]

A statistical study on 565 works of art of different great painters, performed in 1999, found that these artists had not used the golden ratio in the size of their canvases. The study concluded that the average ratio of the two sides of the paintings studied is

Depiction of the proportions in a medieval manuscript. According to Jan Tschichold: «Page proportion 2:3. Margin proportions 1:1:2:3. Text area proportioned in the Golden Section.»[81]

Books and design

According to Jan Tschichold,

There was a time when deviations from the truly beautiful page proportions

and the Golden Section were rare. Many books produced between 1550 and 1770 show these proportions exactly, to within half a millimeter.[82]

According to some sources, the golden ratio is used in everyday design, for example in the proportions of playing cards, postcards, posters, light switch plates, and widescreen televisions.[83]

Flags

The aspect ratio (width to height ratio) of the flag of Togo was intended to be the golden ratio, according to its designer.[84]

Music

Ernő Lendvai analyzes Béla Bartók’s works as being based on two opposing systems, that of the golden ratio and the acoustic scale,[85] though other music scholars reject that analysis.[86] French composer Erik Satie used the golden ratio in several of his pieces, including Sonneries de la Rose+Croix. The golden ratio is also apparent in the organization of the sections in the music of Debussy’s Reflets dans l’eau (Reflections in Water), from Images (1st series, 1905), in which «the sequence of keys is marked out by the intervals 34, 21, 13 and 8, and the main climax sits at the phi position».[87]

The musicologist Roy Howat has observed that the formal boundaries of Debussy’s La Mer correspond exactly to the golden section.[88] Trezise finds the intrinsic evidence «remarkable», but cautions that no written or reported evidence suggests that Debussy consciously sought such proportions.[89]

Music theorists including Hans Zender and Heinz Bohlen have experimented with the 833 cents scale, a musical scale based on using the golden ratio as its fundamental musical interval. When measured in cents, a logarithmic scale for musical intervals, the golden ratio is approximately 833.09 cents.[90]

Nature

Johannes Kepler wrote that «the image of man and woman stems from the divine proportion. In my opinion, the propagation of plants and the progenitive acts of animals are in the same ratio».[91]

The psychologist Adolf Zeising noted that the golden ratio appeared in phyllotaxis and argued from these patterns in nature that the golden ratio was a universal law.[92] Zeising wrote in 1854 of a universal orthogenetic law of «striving for beauty and completeness in the realms of both nature and art».[93]

However, some have argued that many apparent manifestations of the golden ratio in nature, especially in regard to animal dimensions, are fictitious.[94]

Physics

The quasi-one-dimensional Ising ferromagnet CoNb2O6 (cobalt niobate) has 8 predicted excitation states (with E8 symmetry), that when probed with neutron scattering, showed its lowest two were in golden ratio. Specifically, these quantum phase transitions during spin excitation, which occur at near absolute zero temperature, showed pairs of kinks in its ordered-phase to spin-flips in its paramagnetic phase; revealing, just below its critical field, a spin dynamics with sharp modes at low energies approaching the golden mean.[95]

Optimization

There is no known general algorithm to arrange a given number of nodes evenly on a sphere, for any of several definitions of even distribution (see, for example, Thomson problem or Tammes problem). However, a useful approximation results from dividing the sphere into parallel bands of equal surface area and placing one node in each band at longitudes spaced by a golden section of the circle, i.e.

The golden ratio is a critical element to golden-section search as well.

Disputed observations

Examples of disputed observations of the golden ratio include the following:

Nautilus shells are often erroneously claimed to be golden-proportioned.

- Specific proportions in the bodies of vertebrates (including humans) are often claimed to be in the golden ratio; for example the ratio of successive phalangeal and metacarpal bones (finger bones) has been said to approximate the golden ratio. There is a large variation in the real measures of these elements in specific individuals, however, and the proportion in question is often significantly different from the golden ratio.[97][98]

- The shells of mollusks such as the nautilus are often claimed to be in the golden ratio.[99] The growth of nautilus shells follows a logarithmic spiral, and it is sometimes erroneously claimed that any logarithmic spiral is related to the golden ratio,[100] or sometimes claimed that each new chamber is golden-proportioned relative to the previous one.[101] However, measurements of nautilus shells do not support this claim.[102]

- Historian John Man states that both the pages and text area of the Gutenberg Bible were «based on the golden section shape». However, according to his own measurements, the ratio of height to width of the pages is

[103]

- Studies by psychologists, starting with Gustav Fechner c. 1876,[104] have been devised to test the idea that the golden ratio plays a role in human perception of beauty. While Fechner found a preference for rectangle ratios centered on the golden ratio, later attempts to carefully test such a hypothesis have been, at best, inconclusive.[105][74]

- In investing, some practitioners of technical analysis use the golden ratio to indicate support of a price level, or resistance to price increases, of a stock or commodity; after significant price changes up or down, new support and resistance levels are supposedly found at or near prices related to the starting price via the golden ratio.[106] The use of the golden ratio in investing is also related to more complicated patterns described by Fibonacci numbers (e.g. Elliott wave principle and Fibonacci retracement). However, other market analysts have published analyses suggesting that these percentages and patterns are not supported by the data.[107]

Egyptian pyramids